Ernest Hawk, MD, MPH

Karen Colbert Maresso, MPH

In addition to its well-known cardioprotective benefits, aspirin has a substantial body of observational, preclinical, and clinical evidence supporting its efficacy in preventing cancer, most strongly for colorectal cancer.1 The strength of this evidence led the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to recommend low-dose aspirin for the additional benefit of colorectal cancer chemoprevention among those aged 50 to 59 years at elevated risk of cardiovascular disease in 2016.2 However, aspirin’s well-established toxicities, primarily gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, have limited its broader, potential use for primary disease prevention at the population level.

Two articles recently published in JAMA Oncology and reviewed in this issue of The ASCO Post provide more data on aspirin’s potential as a cancer preventive agent from an observational perspective.3,4 These articles, and recent reports from four large randomized controlled trials of aspirin use investigated for an array of possible new indications,5-10 raise new questions regarding aspirin’s chemopreventive potential and highlight the importance of a more holistic and individualized consideration of its risks and benefits by physicians and patients in a clinical setting.

Recent Study Findings: Hepatocellular and Ovarian Cancers

Simon et al reported observational data from a pooled analysis of 2 large, prospective cohorts—the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study—on the association between aspirin use (dose, duration) and hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in 133,371 health-care professionals over more than 26 years (or 4,232,188 person-years) of follow-up.3 The authors reported that regular aspirin use (≥ 2 standard-dose [325-mg] tablets/week) was associated with a statistically significant 49% reduction (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] = 0.51, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.34–0.77) in hepatocellular carcinoma risk compared with nonregular or no aspirin use.

Supporting this association, the risk reduction was both dose- and duration-dependent, requiring a minimum of 5 years of aspirin use, with 1.5 or more standard-dose tablets a week. Somewhat surprisingly, significant risk reductions of a similar magnitude were observed for both patients with cirrhotic and noncirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma. And although the chemopreventive effects of aspirin, nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NA-NSAIDs), and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors have generally demonstrated protective trends for GI-related cancers to date, a similar analysis of NA-NSAIDs in the study by Simon et al did not show a reduction in hepatocellular carcinoma risk.

An inexpensive and accessible chemopreventive agent like aspirin is an attractive strategy to possibly reduce the burden of [hepatocellular carcinoma and ovarian cancer].— Ernest Hawk, MD, MPH, and Karen Colbert Maresso, MPH

Tweet this quote

Barnard et al evaluated the association between aspirin use and ovarian cancer risk also in 2 large, prospective cohorts—Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHS II—involving 205,498 nurses followed for 2 to 3 decades.4 The results demonstrated a significant 23% (HR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.61–0.96) reduced risk of ovarian cancer among those using low-dose (≤ 100 mg) aspirin, but not standard-dose (325 mg) aspirin. There was no association between the duration, cumulative average frequency, or number of tablets of low-dose aspirin use and ovarian cancer risk. Surprisingly, the use of NA-NSAIDs was associated with a 19% (HR= 1.19, 95% CI = 1.00–1.41) increased risk of ovarian cancer, with positive trends for both dose and duration of use.

These NA-NSAID findings are as yet unexplained, but they may represent confounding by indication (eg, symptomatic treatment with NA-NSAIDs for abdominal pain and bloating in those with ovarian cancer); they surely deserve further study because of the frequency of NA-NSAID use by women for menstrual symptoms. If the association was proved to be causal rather than spurious, it could have profound implications for women’s use of these agents for menstrual symptom relief, although this is not anticipated. This study also examined acetaminophen use, but it found no evidence of an association with ovarian cancer risk (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.86–1.21).

Lethal Cancers With Poor Prognoses

These two studies are important because both hepatocellular carcinoma and ovarian cancer are lethal cancers. The overall 5-year survival of hepatocellular carcinoma is dismal, at 18.4%, which is second only to the 5-year survival of pancreatic cancer, at 9.3%.11 The overall 5-year relative survival of ovarian cancer is 47.6%, but this drops to just 29% for the 60% of cases diagnosed at a distant stage.12 Hepatocellular carcinoma etiology is heterogeneous, with hepatitis B and C, alcohol, obesity, tobacco, and aflatoxins all established modifiable risk factors.13 A significant portion of hepatocellular carcinoma cases could be prevented by implementing available evidence-based preventive strategies targeted to these risk factors, yet hepatocellular carcinoma mortality is still rising in the latest national data.13,14

In contrast, ovarian cancer has few established modifiable risk factors and so few preventive strategies. The most potent known risk factor for ovarian cancer is hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome due to BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations.15 However, this syndrome accounts for a minority of ovarian cancer cases. Nevertheless, women at high risk of ovarian cancer due to a BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation may be offered risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy for prevention.16

Chemoprevention: An Attractive Strategy

Given the poor prognoses of both of these cancers, and the suboptimal implementation of preventive strategies targeted to risk factors in the case of hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as the lack of modifiable risk factors in the case of ovarian cancer, an inexpensive and accessible chemopreventive agent like aspirin is an attractive strategy to possibly reduce the burden of these cancers. However, aspirin’s well-known toxicities, primarily GI bleeding, have raised concerns regarding its potential use in primary prevention settings, where its benefits and risks appear to be closely matched. Unfortunately, the reports by Simon et al and Barnard et al did not provide data regarding the risks associated with aspirin use, although an older report from the NHS documented significantly elevated, dose-dependent risks of GI bleeding among regular users of aspirin compared with nonusers; the risk increased from 30% in women taking 2 to 5 standard tablets a week to more than a doubling in risk for women taking more than 14 tablets a week.17

Cardiovascular Risks of Aspirin: Implications for Chemoprevention

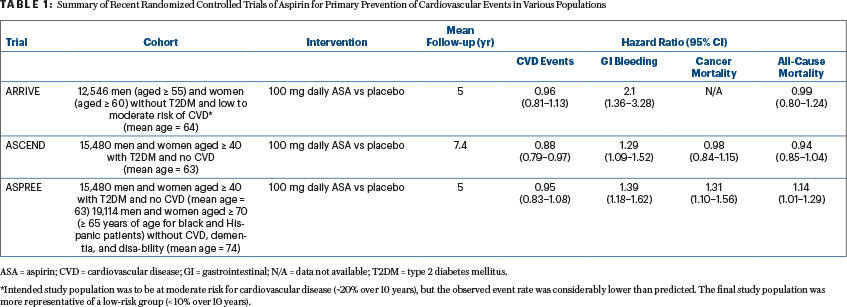

Four recently published randomized controlled trials provide a more global assessment of the full range of aspirin’s benefits and risks in various populations, and they are likely to have implications for the use of aspirin as a chemopreventive agent as well. These trials include outcomes assessing cardiovascular events, GI bleeding, cancer mortality, and all-cause mortality. All-cause mortality is especially important to consider in the case of aspirin, as it provides a measure of the net effect of all of its anticipated benefits and risks across various diseases and indications over the lifespan.

The ARRIVE (Aspirin to Reduce the Risk of Initial Vascular Events) trial intended to enroll nondiabetic men and women at increased risk for cardiovascular disease events (~20% risk over 10 years).6 However, due to a lower-than-expected cardiovascular disease event rate, which the authors attributed to “contemporary risk management strategies,” the study population was more representative of those at low cardiovascular disease risk (< 10% over 10 years).6 The results suggested minimal, if any, benefit of 100 mg of daily aspirin on the reduction of cardiovascular disease events but a significantly increased risk of GI bleeding associated with low-dose aspirin use (Table 1).

A second recent randomized controlled trial, the ASCEND trial (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes), documented a significant cardioprotective benefit of aspirin among people with diabetes, but at the cost of a significant increase in the rate of major bleeding events (Table 1).7

There are enough data to suggest that aspirin might be studied for some fraction of people at increased hepatocellular carcinoma risk, but probably only in the absence of advanced liver disease.— Ernest Hawk, MD, MPH, and Karen Colbert Maresso, MPH

Tweet this quote

In a third randomized controlled trial, data from ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) showed no benefit of aspirin on cardiovascular disease events in the elderly and also demonstrated a significantly increased risk of major bleeding in those taking aspirin in this older age group (Table 1).9 Notably, all-cause mortality also was significantly increased among those taking aspirin in the ASPREE trial, at an average of 5 years of follow-up, driven largely by a perplexing increase in cancer-related mortality (Table 1).8

Although concerning, the ASPREE results need to be interpreted with caution, as they do not align with other published data thus far. For example, although follow-up was limited to 5 to 7.4 years, data in the younger cohorts involved in the ARRIVE and ASCEND studies suggested a null effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality.6,7 In addition, data from ASCEND suggested a null effect on cancer mortality, all-site cancer incidence, GI cancer incidence, and the incidence of several other cancers (ARRIVE has not yet reported on cancer outcomes).7

Taken together, the results of these three trials suggest that the benefits and harms of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in the modern era of preventive management (ie, involving statins, antihypertensives, and smoking cessation) are closely balanced and so call into question the use of aspirin in those without a prior cardiovascular disease event. In fact, in light of these findings, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have moved away from recommending daily low-dose aspirin for the prevention of a first heart attack or stroke in those who are not considered to be at high cardiovascular disease risk, in their recently updated 2019 guidelines.18 Aspirin’s observed null effects on cancer-related outcomes (ASCEND) and all-cause mortality (ARRIVE and ASCEND) are not surprising, given they were secondary outcomes of the trials and follow-up time was limited, with less than the observed 10-year latency period anticipated for colorectal cancer protection.19

Additional follow-up data, as they become available from these trials, as well as data on cancer-related outcomes of the ARRIVE trial, are essential for optimal insights into long-term cancer outcomes. Nevertheless, the observed increase in cancer and all-cause mortality in ASPREE’s older cohort after an average follow-up of 5 years is unexplained and concerning.

Use of Aspirin in Patients With Barrett’s Esophagus

A fourth recently published randomized controlled trial, AspECT (Aspirin and Esomeprazole Chemoprevention in Barrett’s Metaplasia Trial), examined the use of aspirin (300–325 mg/d) along with low- (20 mg/d) and high- (40 mg/d) doses of the proton pump inhibitor esomeprazole in patients with Barrett’s esophagus, with a mean follow-up of 8.9 years.5 Results from this 2 × 2 factorial trial suggested that aspirin was beneficial in this population when combined with high-dose esomeprazole in delaying the time to a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and high-grade dysplasia (aspirin delayed the time to an event by 38% in those taking a high-dose proton pump inhibitor vs those taking a high-dose proton pump inhibitor alone, P = .0680).

In secondary analyses, aspirin had no effect on the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (HR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.62–1.58), although it significantly reduced the risk of high-grade dysplasia (HR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.40–0.95). Its effects on all-cause mortality were suggestive of a benefit, but that outcome was not statistically significant (HR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.59–1.09). The authors reported that just 1% of participants experienced a serious adverse event of grade 3 to 5, with little increase in adverse events when adding aspirin to a high-dose proton pump inhibitor.5

The study authors concluded with a call to review the existing guidelines for patients with Barrett’s esophagus, with the possibility of adding aspirin to the treatment regimen to reduce neoplastic disease progression.5 The authors also suggested that, when given together over a period of years, proton pump inhibitors may reduce the risks of upper GI bleeding associated with aspirin while leaving its anticancer benefits intact—a hypothesis they said should be investigated in large population-based trials of longer duration.5

Take-Home Messages

The results of Simon et al and Barnard et al in conjunction with the recent randomized controlled trials of aspirin in various populations offer at least four take-home messages. First, regarding hepatocellular carcinoma, there are enough data to suggest that aspirin might be studied for some fraction of people at increased hepatocellular carcinoma risk, but probably only in the absence of advanced liver disease (ie, cirrhosis), given the increased risk of acute renal failure and GI bleeding in those with cirrhosis.20 Questions regarding aspirin’s optimal dose, duration, efficacy, safety, and impact within etiologic subsets of liver disease will be of paramount importance to address in this work. Given the growing number of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, it would be particularly useful to examine aspirin’s impact in that population. Interestingly, data from the CAPP2 randomized controlled trial of aspirin in patients with Lynch syndrome, as well as observational data, suggest that obese individuals may derive a particular benefit from aspirin in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer,21 adenomas,22 and endometrial cancer.23

In ovarian cancer, the observed 23% reduction in risk [with aspirin] is important because of the paucity of other agents available for risk reduction, especially in postmenopausal women.— Ernest Hawk, MD, MPH, and Karen Colbert Maresso, MPH

Tweet this quote

Second, in ovarian cancer, the observed 23% reduction in risk is important because of the paucity of other agents available for risk reduction, especially in postmenopausal women. However, it will be important to follow up on the observed NA-NSAID–associated increased risks of ovarian cancer via other observational studies, given the paucity of placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials of NA-NSAIDs, as we learned from the trials of COX-2–selective inhibitors for colorectal cancer risk.24

Third, going forward, it will be critical to assess long-term follow-up data on all potential positive and negative influences of aspirin on health—considering cardiovascular disease risk reduction, cancer risk reduction, GI bleeding risks, and overall mortality—given the important and wide-ranging data that continue to accumulate regarding its range of effects in ‘healthy’ (or at least asymptomatic) populations.

Finally, regarding aspirin’s preventive use today in the general population, it is more important than ever for physicians and patients to engage in shared-decision making. They should consider a holistic assessment of all its potential cumulative risks and benefits in an individualized manner. ■

Dr. Hawk is Vice President for Cancer Prevention; Head, Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences; Professor, Department of Clinical Cancer Prevention, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Maresso is Program Director, Office of the Vice President, Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Hawk has received honoraria from the National Cancer Institute, AACR, Huntsman Cancer Institute, Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, Kansas University Medical Center, The James Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Harbor Biosciences, University of Nebraska Medical Center, American Cancer Society, University of New Mexico ECHO, Rice University, IObiotech, University of Iowa, Mitchell Cancer Institute, City of Hope, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Johns Hopkins Hospital, LSU Health New Orleans, and University of California, Irvine; institutional research funding from NIH/NCI and CPRIT; and travel/accommodations/expenses from NCI, AACR, Huntsman Cancer Institute, Kansas University, Mayo Clinic Cancer Center, The James Ohio State University Comprehensive C ancer Center, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Harbor Biosciences, University of Nebraska Medical Center, American Cancer Society, University of New Mexico ECHO, Rice University, IObiotech, University of Iowa, Mitchell Cancer Institute, City of Hope, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Johns Hopkins Hospital, LSU Health New Orleans, and University of California, Irvine. Dr. Maresso reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Drew DA, Cao Y, Chan AT: Aspirin and colorectal cancer: The promise of precision chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer 16:173-186, 2016.

2. Bibbins-Domingo K, for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 164:836-845, 2016.

3. Simon TG, Ma Y, Ludvigsson JF, et al: Association between aspirin use and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 4:1683-1690, 2018.

4. Barnard ME, Poole EM, Curhan GC, et al: Association of analgesic use with risk of ovarian cancer in the Nurses’ Health Studies. JAMA Oncol 4:1675-1682, 2018.

5. Jankowski JAZ, de Caestecker J, Love SB, et al: Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT). Lancet 392:400-408, 2018.

6. Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, et al: Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE). Lancet 392:1036-1046, 2018.

7. ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al: Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 379:1529-1539, 2018.

8. McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al: Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 379:1519-1528, 2018.

9. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, et al: Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 379:1509-1518, 2018.

10. McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al: Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 379:1499-1508, 2018.

11. Villanueva A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 380:1450-1462, 2019.

12. National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program: Cancer Stat Facts: Ovarian Cancer. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed May 15, 2019.

13. Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, et al: Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 68:31-54, 2018.

15. Gayther SA, Pharoah PD: The inherited genetics of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20:231-238, 2010.

16. Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, et al: Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA 304:967-975, 2010.

17. Huang ES, Strate LL, Ho WW, et al: Long-term use of aspirin and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Med 124:426-433, 2011.

20. Ge PS, Runyon BA: Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 375:2104-2105, 2016.

21. Movahedi M, Bishop DT, Macrae F, et al: Obesity, aspirin, and risk of colorectal cancer in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: A prospective investigation in the CAPP2 study. J Clin Oncol 33:3591-3597, 2015.

22. Kim S, Baron JA, Mott LA, et al: Aspirin may be more effective in preventing colorectal adenomas in patients with higher BMI (United States). Cancer Causes Control 17:1299-1304, 2006.

23. Neill AS, Nagle CM, Protani MM, et al: Aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol and risk of endometrial cancer: A case-control study, systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 132:1146-1155, 2013.

24. Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, et al: Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: The cross trial safety analysis. Circulation 117:2104-2113, 2008.