A Century of Progress

The text and photograph on this page are excerpted from a four-volume series of books titled Oncology Tumors & Treatment: A Photographic History, by Stanley B. Burns, MD, FACS. The photo below is from the volume titled “The Antiseptic Era: 1876–1900.” To view additional photos from this series of books, visit burnsarchive.com.

The Antiseptic Era 1876–1900

Philadelphia, 1896

The last of the medical milestones to shape modern surgical practice in the 19th century was the discovery of the x-ray by physicist Wilhelm Röntgen. The professional and public response to this new form of photography was immediate and enthusiastic. Scientists around the world labored to construct their own x-ray machines.

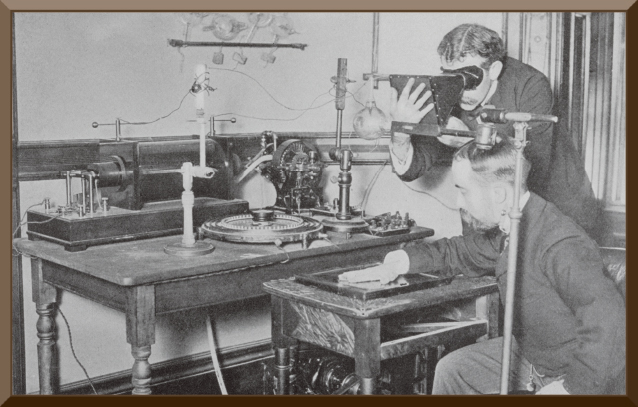

In Philadelphia, William J. Morton, MD (1846–1920), working with electrical engineer Edwin W. Hammer, produced an x-ray apparatus and a fluoroscope. They aggressively proceeded to x-ray a variety of objects, such as diseased body parts and even a whole infant. Dr. Morton and Mr. Hammer planned to market copies of their x-rays to their fellow doctors as a teaching tool. This would give other physicians a chance to familiarize themselves with the new technology and learn how to read the film.

At that time, Dr. Morton’s collection was the largest in the United States. Within 9 months after the appearance of this invention, Dr. Morton and his engineer published the first book on radiology in America: The X-Ray: Or, Photography of the Invisible And Its Value in Surgery. (Dr. Morton was also the first to perform dental radiography in America.)

As part of the series of x-rays, the authors published this image of themselves using their apparatus. Dr. Morton is seen fluoroscoping his own hand. Medical pioneering was nothing new to the Morton family; his father, dentist William T. Morton (1819–1868), was the first to publicly demonstrate the anesthetic effects of sulphuric ether at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1846.

Hazards and Benefits

Obviously, early radiologists were unaware of the hazards of unprotected exposure to x-rays. A scene such as this makes modern observers recoil at the prospect of increased health risks. Because there was a tremendous variance in the output of early x-ray tubes, radiologists routinely tested them by observing the distinctness of their hands against a fluoroscopic screen.

In this early era, exposure time for an x-ray could not only take an hour, but could also require repeated exposures to capture an adequate image. All during this ordeal, both patients and the operator were unprotected. Many of the early pioneers died prematurely of cancer. Others, such as Johns Hopkins’ first Chief of Radiology, Frederick Henry Baetjer, MD, spent years incurring partial amputations and treatment for malignancies. Dr. Baetjer had organized the radiology department in 1902 and died in 1933 at the age of 59.

The therapeutic effects of radiation were recognized soon after its invention. Skin diseases were the first to be treated. In 1896, a few months after its presentation, radiation was used for the treatment of breast cancer. By 1901, pioneer radiologists were using radiation as cancer therapy for inoperable cases and for pain relief in advanced disease states. ■