Finding salvageable colon cancer recurrence is akin to finding a needle in a haystack, rendering routine patient surveillance of little value. But finding that needle offers an opportunity for treating recurrent disease early, which makes surveillance worthwhile. These were the opposing views presented by two surgical oncology experts in a “Great Debate” at the 2014 Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) Annual Cancer Symposium in Phoenix.1

George J. Chang, MD, MS, FACS, FASCRS, made the case for colorectal cancer surveillance as a waste of resources, while Elin R. Sigurdson, MD, PhD, FACS, defended the value of such surveillance.1 Dr. Chang is Associate Professor of Surgical Oncology, Chief of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Director of Clinical Operations, Minimally Invasive and New Technologies in Oncologic Surgery Program, and Associate Medical Director of the Colorectal Center at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Dr. Sigurdson is Chief of the Division of General Surgery at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia.

Three Strikes Against Surveillance

Dr. Chang listed the three main goals of colorectal cancer surveillance:

- Improve patient survival through detection of of potentially curable recurrence and metachronous tumors.

- Detect asymptomatic recurrence for palliative therapy.

- Offer psychological support and improve quality of life.

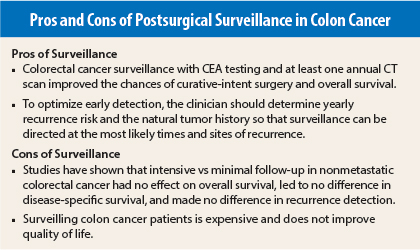

However, Dr. Chang argued, surveilling these patients is expensive, does not improve survival, and does not lead to a better quality of life.

Cost Issues

To address the issue of cost, Dr. Chang created a model of the yield of surveillance imaging with the assumption that computed tomography (CT) scanning had a 100% detection sensitivity for recurrence. He calculated that the recurrence rate after resection would be 5% for stage I disease, 15% for stage II, 30% for stage III, and 60% for stage IV disease.

With a 15% salvage rate following recurrence and 5 years of follow-up, “the yield of a CT scan in stage I disease is 1%,” Dr. Chang explained. “The yield of a CT scan in stage III disease is 6% for recurrence. And if we look at the yield of salvageable recurrence, it’s 0.9% of all the imaging tests performed in stage III disease.”

Working with this same model and calculating what he called “back of the envelope” figures, Dr. Chang said the total cost for the recommended chest, abdomen, and pelvic CTs would be $6,300 per patient per surveillance episode. The combined cost for other components of surveillance—carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) testing, colonoscopy, and the office visit—would come in at $2,700.

“Assuming a 5-year follow-up, we can see the total cost … is $38,500, assuming one CT scan per year. Assuming two CT scans per year—we know that a lot more imaging is performed than what I’ve indicated in this model—the cost is $70,000 for stage IV disease,” he said.

“The cost of recurrence based on the numbers that I presented earlier is almost $1 million in stage I. The cost of one salvage is almost $4 million. In stage II, it’s not that much better; it’s $1.3 million for salvage and that’s not to say that the person survived.”

Survival Not Improved

In terms of improving survival, multiple studies have demonstrated surveillance does not do the job, Dr.

Chang said.

A Cochrane systematic review of intensive vs minimal follow-up in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer showed no effect on overall survival, no difference in disease-specific survival, and no difference in recurrence detection.2

A more recent study looked at the effect of 3 to 5 years of scheduled CEA and CT follow-up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer. Those investigators reported that the number of deaths was not significantly different in the combined intensive monitoring groups (18.2%) vs the minimum follow-up group (15.9%). “If there is a survival advantage to any strategy, it is likely to be small,” they concluded.3

Dr. Chang cited interim analysis from the ongoing Gruppo Italiano di Lavoro per la Diagnosi Anticipata (GILDA) trial, which is evaluating follow-up of colon cancer patients after resection with curative intent. At a mean duration of follow-up of 14 months, the investigators found similar rates of relapse (15% vs 13%) and death (7% and 5%) in the intensive and less-intensive follow-up arms.4

Quality of Life

“If we can’t find a difference in recurrence, and we can’t find a difference in cancer-specific survival, and we can’t find a difference in overall survival, can we at least improve the quality of life?” Dr. Chang asked.

The answer is “no,” according to Dr. Chang, who relied on data from two studies—one in breast cancer and one in colon cancer—to prove his point.

A study published in 1994 sought to determine the impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer. “The summary is that there’s no difference in quality of life among patients who received intensive surveillance and those who got minimalist care,” Dr. Chang stated.5

Finally, a study of colorectal cancer patients’ attitudes toward follow-up and what it meant to their quality of life turned in less-than-positive results. “Follow-up exams were burdensome for one in two patients,” Dr. Chang said in summarizing the findings. “One in three patients found that follow-up reminded them too much of their disease. There are potential harms to follow-up.”6

Dr. Chang concluded that “expending resources to find the needle in the haystack does not result in a clinically meaningful increase in the rate of detection of recurrence. Follow-up does not improve cancer-related survival. Follow-up is resource-inefficient. Follow-up does not improve quality of life, but may be a frequent source of inconvenience and anxiety [for patients].”

Surveillance: Worth Every Penny

Dr. Sigurdson also began her talk by outlining why surveillance is done after colon cancer resection:

For early detection of recurrence, to increase incidence of resectable recurrence, and to improve survival with early initiation of therapy

- To assess shared risk factors that may increase risks of second primary cancers

- To assure patients they are “disease free”

- As a mark of good practice

Early detection means determining yearly recurrence risk and the natural tumor history. That way, surveillance can be directed at the most likely times and sites of recurrence. “You want to limit your resource expenses by focusing on the high-risk time,” Dr. Sigurdson stated.

She cited data from two studies to demonstrate that the time and sites of recurrence in colorectal cancer are well known. A 2002 study found that the risk for second primary colon cancer was 1.5% at 5 years.7 Another study noted that distant recurrence in stage II and stage III disease was most likely in the first 3 years, and that risk tapered down by year 8. Having these data “allows us to modify the number of colonscopies that are done,” she explained. “When I was training, they were being done annually. We have been able to extend that out to 3, 5, and 10 years.”8

COST Trial

An analysis of the Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy (COST) trial looking at sites of recurrence found that liver and lung metastases, as well as locoregional recurrence, were the main areas of concern. The authors reported that patients with early-stage colon cancer have similar sites of recurrence and receive benefit from postrecurrence therapy similar to that seen in patients with late-stage disease.9 Most important, according to Dr. Sigurdson, salvage resection was similar in both arms of COST (36% vs 37%), with about one-third of patients having resectable disease at recurrence.

In a trial that focused on liver resection, about 40% of patients were alive at 5 years, with a median survival of 3.6 years.10

Moving on to the benefits of the early initiation of therapy, Dr. Sigurdson noted that median overall survival was 6 months when best supportive care was the only option. Survival rates jumped to 1 year after the introduction of fluorouracil chemotherapy. Now, with newer chemotherapy agents, survival is in the 30-month vicinity, she said.

Dr. Sigurdson explained that these survival figures apply to patients with “a very good performance status. Patients who are identified with advanced disease and poor performance status, picked up by symptomatology, have a median survival of 2 years. So early recognition of distant disease is beginning to make a difference. These early, intensive surveillance projects allow us to find those patients.”

Finally, surveillance allows clinicians to look for other cancers in colorectal cancer patients who have certain risk factors such as diabetes, obesity, and alcohol consumption.

Best Test?

Dr. Sigurdson finished her argument with a question: What is the best test for surveillance? She also highlighted results from the FACS randomized trial led by John Primrose, MD, FRCS, indicating that patients with resectable disease were found by imaging or CEA testing. Most of the recurrences were detected by routine investigation, and among patients who had recurrence resected, 69% were still alive at a median follow-up of 4.4 years, she pointed out.

Dr. Sigurdson concluded that colorectal cancer surveillance with CEA testing and at least one annual CT scan improved the chances of curative-intent surgery and overall survival. In addition, no studies have adequately demonstrated a negative impact on quality of life with colorectal cancer surveillance.

Indeed, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines call for CEA testing every 3 to 6 months for 2 years and then annual CT scanning up to 5 years, she said.

Debate Rebuttals

In his response, Dr. Chang asked if surveillance was worth the cost. He emphasized, “I’m not arguing that we shouldn’t attempt salvage in patients in whom recurrence is identified. I’m certainly not arguing that salvage of recurrent disease [lacks benefit]. The point is, regardless of how we look for it—or don’t look for it—our ability to detect [recurrence] is the same.… Our ability, therefore, to salvage is not that different.”

Instead, Dr. Chang suggested a compromise. “We know that the risk of recurrence is the highest early on and that ‘very early’ recurrence is probably preexisting disease…. In fact, [surveillance at] a single point in time, such as at 1 or 2 years, may be enough to get the highest yield and greatest value on our investment.”

Dr. Sigurdson argued that the best way to offer optimal care is to follow the guidelines for surveillance. She cited a study done by Dr. Chang and colleagues that found “survival benefit for patients with stage III and high-risk stage II colon cancer who received treatment that adhered to NCCN guidelines.”11 ■

Disclosure: Dr. Chang reported relationships with Ethicon Endo-Surgery and Agendia. Drs. Sigurdson and Primrose reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Chang GJ, Sigurdson ER: Follow-up after colorectal surgery: Wasting resources? 2014 SSO Annual Cancer Symposium. Presented March 15, 2014.

2. Jeffery M, Hickey E, Hider PN, et al: Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD002200, 2007.

3. Primrose MD, Perera R, Gray A, et al: Effect of 3 to 5 years of scheduled CEA and CT follow-up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer: The FACS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311:263-270, 2014.

4. Grossmann EM, Johnson FE, Virgo KS, et al: Follow-up of colorectal cancer patients after resection with curative intent—the GILDA trial. Surg Oncol 13:119-124, 2004.

5. Ghezzi P, Magnanini S, Rinaldini M, et al: Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. The GIVIO Investigators. JAMA 271:1587-1592, 1994.

6. Stiggelbout AM, de Haes JC, Vree R, et al: Follow-up of colorectal cancer patients: Quality of life and attitudes towards follow-up. J Cancer 75:914-920, 1997.

7. Green RJ, Metlay JP, Propert K, et al: Surveillance for second primary colorectal cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy: An analysis of Intergroup 0089. Ann Intern Med 136:261-269, 2002.

8. Sargent DJ, Patiyil S, Yothers G, et al: End points for colon cancer adjuvant trials: Observations and recommendations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients enrolled onto 18 randomized trials from the ACCENT Group. J Clin Oncol 25:4569-4574, 2007.

9. Tsikitis VL, Malireddy K, Green EA, et al: Postoperative surveillance recommendations for early stage colon cancer based on results from the clinical outcomes of surgical therapy trial. J Clin Oncol 27:3671-3676, 2009.

10. Kanas GP, Taylor A, Primrose JN, et al: Survival after liver resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: Review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. Clin Epidemiol 4:283-301, 2012.

11. Boland GM, Chang GJ, Haynes AB, et al: Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer 119:1593-1601, 2013.