In this installment of Living a Full Life, Guest Editor Jame Abraham, MD, FACP, spoke with Mark A. Lewis, MD, Director of Gastrointestinal Oncology at Intermountain Healthcare, Murray, Utah, and Vice President of American Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Support. Dr. Lewis is also a social media influencer within the oncology community, where he energizes lively discussions on Twitter and elsewhere on topical issues in oncology and public health care.

MARK A. LEWIS, MD

On his hereditary cancer: “This diagnosis has truly informed my career, because I cannot avoid treating patients without looking at it through the lens of a patient myself.”

On the value of social media in oncology: “Even though I didn’t really know anybody who had MEN-1, I was able to find kindred spirits online.”

On live-streaming his Whipple surgery: “It took a lot of coordination, but that experience completely transformed my belief in social media as a crucial way not only to communicate with our peers, but also with the public.”

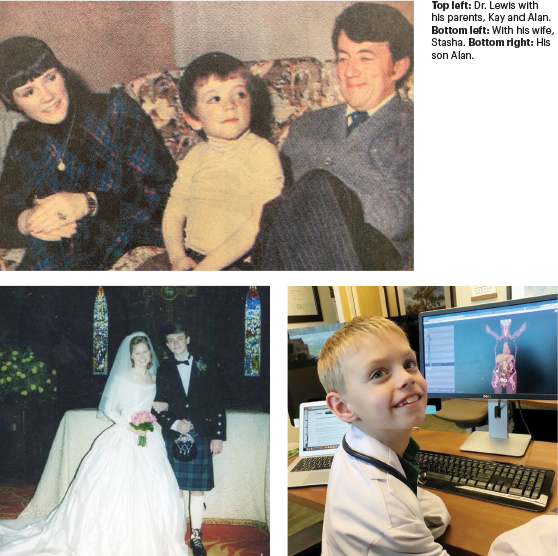

According to Dr. Lewis, cancer has been a personal presence in his life since early boyhood. “I was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, and when I was 8 years old, our family emigrated to America, settling in Texas, which was quite a culture shock. Part of the public health immigration process involved getting a chest x-ray to rule out things like infectious tuberculosis. At the time, my father was 42 years old, a nonsmoker who was seemingly in robust health. So, it came as quite a shock when we got word from an official call from the embassy saying that my father didn’t have tuberculosis and was free to travel, but a large mass was detected in his right lung, and he should get it looked at as soon as we arrived in America,” he said.

Dr. Lewis continued: “Soon after arrival, we became involved in the U.S. health-care system. Unfortunately, my father had to have his entire right lung removed; but by then, the cancer had already spread into the mediastinum, and he underwent radiation and chemotherapy but ultimately passed away. There were no doctors in my family; my father, in fact, was a minister, and my first exposure to medicine was his oncologist, who delivered what was then state-of-the-art treatment, which gave us 7 years with my father. My father’s battle with cancer and ultimate death from the disease was a driving factor in my decision to become an oncologist.”

Dr. Lewis developed a relationship with his father’s oncologist, Richard Helmer, MD, which carried on during his high school years and into college. “Dr. Helmer took me under his wing, and every summer I got to work in his clinic, where I observed the intimate practice of oncology. I also worked as a medical assistant and an x-ray technician, but, most importantly, I literally got to follow Dr. Helmer and see the personal attention he gave to patients with cancer. That was in the day of the paper chart, and Dr. Helmer would literally carefully write not just the pertinent clinical details, but also the personal aspects of each patient, in a very genuine way, so he was able to connect with them during the continuum of care,” he related.

GUEST EDITOR

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

Pain and a Eureka Moment

Dr. Lewis received his medical degree and completed his internal medicine residency at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, where he also served as chief resident before he began a hematology/oncology fellowship at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. On Dr. Lewis’ first day of training, he awoke with severe abdominal pain, a manifestation of a high calcium level.

“And that was my Eureka moment because I had never dreamed my father’s cancer was hereditary. But he experienced high calcium during his entire adulthood, and there’s only two known conditions that present like that in consecutive generations: benign, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia and the hereditary tumor syndrome multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1). Looking back, it hit me like a bolt of lightning as I realized my father’s tumor was caused by MEN-1. So, it all fit together, this is the clinical familial pattern I’m in,” said Dr. Lewis.

After his unsettling discovery, Dr. Lewis went to the internist he’d been assigned at Mayo during the first week of his oncology training and explained he had a cancer syndrome. “It took a bit of convincing because I think he was worried that I was verging on paranoia for hypochondriasis. But I basically laid out the case that it was either MEN or familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia. From the outside looking in, it was an interesting scenario because of the ethical quandary of a doctor trying to diagnose himself and offer a treatment plan. In the end, this diagnosis has truly informed my career, because I cannot avoid treating patients without looking at it through the lens of a patient myself,” said Dr. Lewis.

Choosing a Specialty

After completing his hematology/oncology fellowship at the Mayo Clinic, he returned to Houston to work at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. “After my fellowship, we moved back to Texas, and I worked at MD Anderson, where I had a dual appointment in both gastrointestinal (GI) oncology and general oncology. As you may know, most of MD Anderson is predicated on subspecialization, and there were even house jokes that we had doctors for left-sided and right-sided renal cell carcinoma. However, I realized I had to pick one or the other; because of my own issues with MEN-1 and my love for diving deep into an issue, I chose GI oncology, and it’s my job ever since.”

In 2016, a position opened at Intermountain Healthcare, which is a multistate health-care system sometimes called the Kaiser of Utah. Dr. Lewis commented: “Coming here was a great move because Intermountain has allowed me to specialize in GI oncology and also spend a good amount of my time figuring out how to distribute care across a vast geography, which is a passion of mine,” he explained.

Social Media

During the early course of Dr. Lewis’ treatment, he had an epiphany of sorts about the value of properly leveraged social media in oncology. “Even though I didn’t really know anybody who had MEN-1, I was able to find kindred spirits online. That was very formative for me, too, the awareness of these large patient communities and groups of advocates and caregivers and patients themselves who exchange information. It’s almost like this society you get to enter, but the cost of membership is having the illness or being at least very close to illness. It operates nearly autonomously from our medical community,” he explained.

Dr. Lewis continued: “I feel very lucky to be able to stand in both worlds. I know some of our colleagues are still wary of social media and of these groups, and I’m not in any way disparaging them. They worry about the information that’s being exchanged there. But I must tell you, I think the benefits far outweigh the risks in terms of what patients themselves get in terms of kinship. In addition, the degree of savvy of information and sophistication in these groups is pretty staggering. I think we in the practice of oncology underestimate that or perhaps don’t understand it enough.”

Twitter the Public Space

Dr. Abraham asked about Dr. Lewis’ transition to the fast-and-furious Twitter space. “My first dive into social media was on Facebook, interacting with other patients who had MEN-1. So, a nurse and I founded a private group for patients with MEN-1 and MEN-2, which has now grown to several thousand members. It’s interesting to see that level of participation and dialogue, which is far less about the most cutting-edge clinical trial, although there is discussion of research; it’s more centered on accessing the standard of care. Seeing that was very constructive, but eventually what came to interest me was how to interface with the public on a platform like Twitter?” he said.

According to Dr. Lewis, he was first introduced to Twitter during his time at MD Anderson Cancer Center by Michael Fisch, MD. “Michael was proposing that I use Twitter as a curation tool for my reading and ruminations, but I soon realized the other fascinating thing about Twitter is it is deliberately open to everybody. That’s not a bug, that’s a feature. And it gave me the platform to get away from the stereotype of an oncologist as an unfeeling scientist, absorbed with numbers and data instead of the human impact of cancer.”

Then, Dr. Lewis thought that the best way to do that was to put his money where his mouth. We literally live-streamed my Whipple surgery in 2017, online in real time. And it took a lot of coordination, but that experience completely transformed my belief in social media as a crucial way not only to communicate with our peers, but also with the public. And does it work perfectly? No. Are there trolls? Yes. But the vast majority of what I’ve gotten from engaging in social media has been a huge benefit,” he related.

Work-Life Balance as a Doctor/Patient

Asked about balancing his life with the ongoing challenges of his MEN-1 condition, Dr. Lewis said: “My wife, Stasha, is a pediatrician here at Intermountain, and I’ve been so fortunate to have her as a spouse in every respect. I had some complications after my Whipple, and there were literally things she did that kept me out of the emergency room. For example, I had gastric outlet obstruction, and Stasha placed a nasogastric tube at home.”

In addition, Dr. Lewis and his wife were concerned that since he has a genetic condition with autosomal dominant inheritance, there was a 50/50 chance that each one of their children might inherit this from him. “We have two kids, and that’s exactly the way the math worked out,” said Dr. Lewis. “My 14-year-old daughter, Emma, is totally fine, but my 11-year-old son, Alan, who’s named after my dad, does have the mutation. I think that unless there’s some CRISPR [clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats] miracle in his lifetime, it is going to be a lifelong condition for him, too. And right now, he’s 11 and in fantastic health.”

The big question Dr. Lewis and his wife faced was how to tell a young boy that he has an incurable diagnosis. “We did that when he was younger, because we didn’t want him to be weighed down with it. But also, we wanted him to understand this is a part of his identity, just as much as his eye color. There are all different ways of looking at genetic conditions; rather than making it our family curse, we’ve tried to take my wife’s pediatric expertise and my oncologic insights to make childhood for our son as normal as possible. He actually enjoys MRI scans because they mildly sedate him with laughing gas.”

Asked how he de-compresses after a long day, Dr. Lewis said: “Being from Britain, I still love soccer, or as we would call it football. So, I do follow Manchester United and like Formula One racing. My father was a big Formula One fan. We live here in Utah, just at the base of the mountains. In the winter, we ski together, but honestly in my free time for what it’s worth, I mostly spend it with my wife and kids.”

Closing Thoughts

“I have two drawers in my office: one in which I keep my patients’ obituaries. It sounds very grim, but actually it’s a reminder of all the people I’ve gotten to take care of who have passed on. But then next to it, I have this other drawer, which is such a blessing because it’s full of thank-you notes. Whenever I look in the obituary drawer, I always look in the thank-you note drawer. I find it interesting that a lot of oncologists I’ve learned have keepsakes like this; it humanizes us. Then even if people die, hopefully we have helped them while they were still living. I think there’s a lot of value there, even if we’re not making anyone immortal.”

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Lewis reported no conflicts of interest.