Last year’s health-care reform legislation, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, was designed to incrementally roll out major new bureaucratic entities, oversight, and mandates for the practice of medicine between its enactment and 2013, after the next presidential election. A new lexicon for medical care was also introduced, including “accountable care organizations” and “meaningful use.”

These changes to medical care systems make the physician first accountable to federal mandates that are intended to standardize care and advocate on behalf of the patient. This assumes that, prior to the passage of the legislation, physicians were not accountable, and that the health care delivered had no meaningful impact on patient outcomes. But the ethics of medicine hold duty to the patient first and foremost; it is the patient who holds the physician accountable for the quality of care delivered.

Survival and Chronic Disease

The steady advancements in U.S. medical care have had a meaningful impact that increased both quality-of-life and survival rates, as evidenced by a burgeoning retirement age population. According to the Congressional Research Service, the average life expectancy was 49 years in 1900, 59 years in 1930, 70 years in 1960, 75 years in 1990, and 77 years in 2003. In 2009, the World Bank posted the U.S. average life expectancy as 79 years.

Early leaps in survival resulted from the control and treatment of infectious diseases with vaccines and antibiotics. Since the 1960s, incremental increases have resulted from advances in the diagnosis and treatment of heart disease and cancer. The fastest growing segment of the U.S. population comprises those aged 80 years and older, with a growth rate four times that of the total population. Perhaps physicians and health-care systems have done their job too well.

The diagnosis and treatment of chronic disease, however, has become the more prominent issue, as approximately 75% of all health-care costs relate to the treatment of chronic disease. The rapidly expanding population over the age of 65 years, and the use of Medicare and Social Security payroll tax revenue within general government revenues, has placed significant financial strain on these social programs.

Role of Government

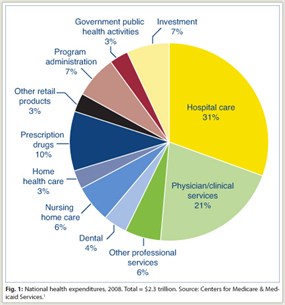

For all the debate regarding the cost of health care, however, only 31% of the cost is attributed to hospital care, 21% to physician/clinical services, and 10% to prescription drugs (Fig. 1). The remaining 39% of national health expenditures includes 7% for administrative costs for billing and regulatory compliance—almost as much as that spent on all prescription drugs in the United States. An additional 7% includes investment in new technologies and in health information technology systems.1

For all the debate regarding the cost of health care, however, only 31% of the cost is attributed to hospital care, 21% to physician/clinical services, and 10% to prescription drugs (Fig. 1). The remaining 39% of national health expenditures includes 7% for administrative costs for billing and regulatory compliance—almost as much as that spent on all prescription drugs in the United States. An additional 7% includes investment in new technologies and in health information technology systems.1

The government has, incrementally, assumed a dominant role in health care. With the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1964, the federal government rapidly increased its share of health-care spending from 10% to nearly 25% in 1965.

Currently, over 35 million Americans are enrolled in Medicare. Over 50 million Americans now receive Medicaid, at a cost of $273 billion—a 36% jump since 2008 due to the failing economy—and 16 million more will be added to Medicaid by 2014 under the new Affordable Care Act criteria. More than half of all Americans are now enrolled in a federal health-care insurance program.

More about Cost, Less about Quality

As the debate over the budget and debt ceilings intensifies, the Medicare issue is really more about the cost and less about the quality of U.S. medical care. The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act begs the question, affordable to whom? The Congressional Budget Office has reported that the coverage provisions will cost $1.445 trillion between FY2012 and FY2021, despite the $500 billion cut in Medicare benefits.

Under the legislation, the $500 billion cut in Medicare targets reimbursement of health-care providers, and will be achieved through the following2:

- Permanent reductions are being made in the annual updates to Medicare’s fee-for-service payment rates (10-year savings of $196.3 billion).

- Maximum payment rates in the Medicare Advantage program are closer to or below fee-for-service levels (10-year savings of $135 billion).

- Medicare payments to hospitals that serve a large number of low-income patients, known as disproportionate share hospitals, will be reduced (10-year savings of $22 billion).

- A high-income adjustment will be made for Part B premiums (10-year savings of $25 billion).

- An Independent Payment Advisory Board was created to further reduce Medicare payment rates (10-year savings of $16 billion).

- A new hospital insurance tax on taxable wages over $200,000 per year for single filers/$250,000 for joint filers will raise $87 billion between FY2013 and FY2019.

- A new tax on investment income will raise an additional $123 billion over 10 years.

New Payment Models

Under the Affordable Care Act, government sanctioned accountable care organizations will require health-care systems to be accountable for the cost as well as the quality of health care. The new model is charged with “restructuring traditional Medicare coverage” and must create a prospective budget and resource assessment. Compliance with the 15 core measures under meaningful use requires significant investment in health information technology and administrative staff, and will further strain the financials of health-care systems.3

New payment models are established, and Section 3022 of the Affordable Care Act requires participation in a Medicare Shared Savings Program by January 1, 2012. The Shared Savings Program will shift from volume-based to value-based rewards. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Director Donald Berwick indicated that financial opportunities for accountable care organizations to achieve shared savings “will vary according to its initial tolerance for risk.”3 The accountable care organization payment models, Shared Savings Program, Partial Capitation Model, and Fully Capitated Model are based on the level of risk and patient population. Capitated models were widely used in the 1990s with private sector health maintenance organizations, which caused significant problems with access to specialty care. The difference now is that the government, rather than a private sector entity, is the gatekeeper for access to medical care.

The Shared Savings Program must meet cost targets and is better suited to lowest-risk populations. The Partial Capitation Model places the accountable care organization at risk for the cost of some Medicare services. Finally, the Fully Capitated Model provides global payments, at the discretion of the Secretary of Health and Human Services, for services delivered to high-risk populations. To make up for lost reimbursement and meet the criteria set in the Affordable Care Act, health-care systems must improve efficiency, optimize bed capacity, and invest heavily in health information technology.4

Can Efficiency Be Improved Adequately?

The ability of health-care systems to sufficiently improve efficiency to make up for the Affordable Care Act’s reimbursement cuts is in question. The results of a Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration Project between 2005 and 2010, involving 10 large physician groups with high information technology penetration and financial solvency, are concerning. Targeting coronary artery disease, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and preventive care, the criteria were met in only 2 of the 10 groups at the end of year 1, 4 groups in year 2, and in only half of the groups by year 3 of the project. To meet the criteria, the groups made an average $1.7 million infrastructure investment, and most of these physician group practices did not break even on their initial investment. The calculated operating margins required to recover costs were 20% over 3 years, 13% for 5 years, and 8% for a 10-year payback.5 At the end of 5 years, only 6 of 10 groups produced a savings totaling $78 million over 5 years. On average, this is a savings of $2.6 million per year per group for those that were successful in cost savings.

CMS Director Berwick, however, indicated that it was necessary to spend resources to reduce unnecessary services, health information technology was critical, and physician leadership was necessary to motivate implementation of the changes in practice. The newly created Center for Medicare/Medicaid Innovation concurrently is launching “aggressive testing” of nationwide technical support for accountable care organizations to complement ongoing private sector efforts.3

Other Requirements

While a significant investment in health information technology will be needed by some health-care entities, additional administrative staff will also be required to ensure compliance with the 15 core meaningful use measures, and for the submission of reports to the federal government. Under the concept of meaningful use, physicians must have the capacity to “submit electronic syndrome surveillance data to public health agencies and actual submission according to applicable law and practice.”

Additionally, more than 80% of patients must have a problem list of active diagnoses. Lists must be generated for quality improvement, reduction of disparities, research, and outreach. Physicians initially must implement one clinical decision “relevant to the medical specialty or a high clinical priority, along with the ability to track compliance”; and there should be clinical decision support that is “intelligently filtered and organized to enhance health and health care,” although “CMS will not issue additional guidance” along these lines.

Improvements in medical care, along with a strong tradition of the doctor-patient relationship, have significantly improved the lives of Americans. This relationship determined meaningful patient-centered medical care based on individual circumstances. Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, accountability of care and meaningful medical practice is now under the control of the payer, ie, the government. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Janjan has served as a consultant to Bayer Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Janjan is Senior Fellow in Healthcare Policy and Dr. Goodman is President and CEO, National Center for Policy Analysis, a nonprofit think tank established in 1983 and headquartered in Dallas.

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: National health expenditures by type of service and source of funds, CY 1960–2009. Available at http://www.cms.gov. Accessed June 8, 2011.

2. Davis PA, Hahn J, Morgan PC, et al: Medicare provisions in PPACA (P.L. 111-148). Congressional Research Service. April 21, 2010. Available at http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/11-148_20100421.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2011.

3. Berwick DM: Launching accountable care organizations—the proposed rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med 364(16):e32. Epub March 31, 2011.

4. Berkowitz SA, Miller ED: Accountable care at academic medical centers—lessons from Johns Hopkins. N Engl J Med 364(7):e12. Epub Feb 2, 2011.

5. Haywood TT, Kosel KC: The ACO model—a three-year financial loss? N Engl J Med 364(14):e27. Epub Mar 23, 2011.