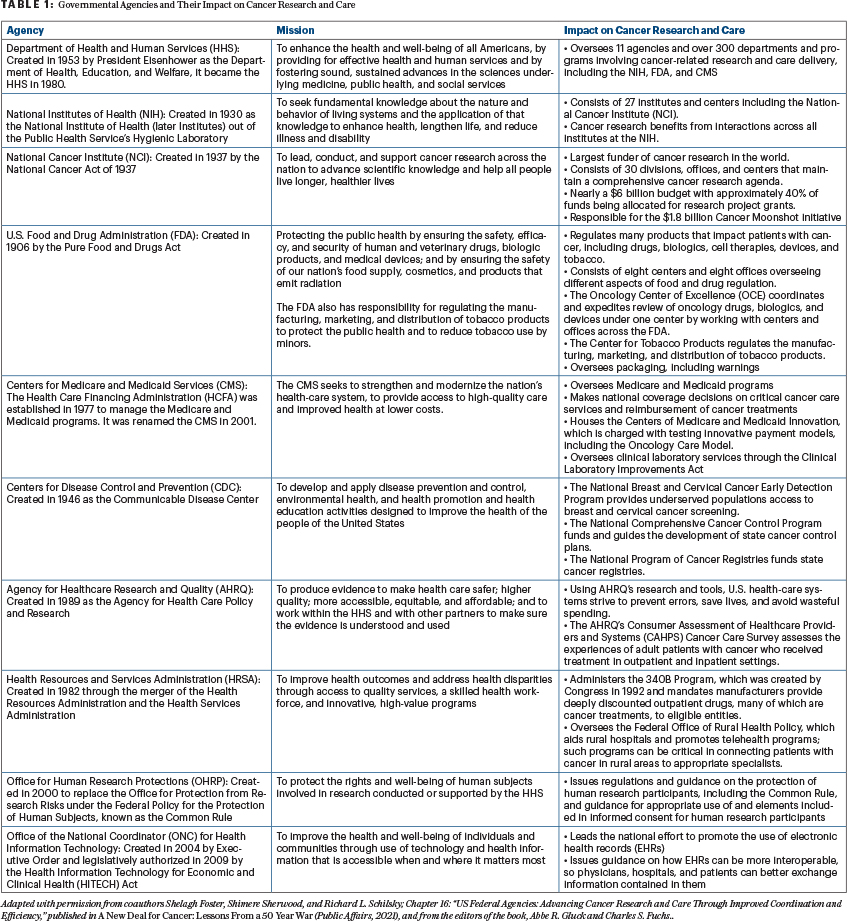

President Richard M. Nixon signed the National Cancer Act into law on December 23, 1971. The unprecedented legislation granted sweeping authority to the Director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to develop a national cancer program that included the NCI, other research institutes, and federal and nonfederal programs; funding to establish 15 new cancer research centers and local control programs; and an international cancer research databank. The U.S. Federal government now has multiple agencies and departments that significantly impact the outcomes of people with cancer, as they support, advance, and drive trends in cancer research, or have direct or indirect influence over coverage, reimbursement, or the overall provision of or access to cancer care. These agencies directly fund cancer research, oversee the way research is conducted, regulate medical products used in cancer treatment, and govern the delivery of cancer care (see Table 1).

The large number of federal agencies involved can present barriers to advancing cancer care by imposing regulatory roadblocks, creating uncoordinated silos, or failing to keep pace with the breakneck speed at which cancer research is moving. Because of their distinct jurisdictions and varied technical expertise, agencies sometimes act in silos, merely completing their “step” in the process, rather than working together to improve the efficiency of cancer research and care delivery. Increased collaboration among agencies would eliminate redundancies, reduce confusion among stakeholders, speed therapies to patients, and better support providers in their efforts to deliver quality and equitable care to patients.

Coordinating Research Efforts Between the Public and Private Sectors

As the anchor of the nation’s cancer research efforts, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) is the largest public funder of cancer research in the world. Established by the National Cancer Act of 1937, it manages a complex web of intramural and extramural research efforts. The NCI organizes and supports the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN), with more than 2,200 sites that conduct cancer clinical trials, primarily across the United States and Canada. The NCTN and the related National Community Oncology Research Program provide the primary infrastructure for NCI-funded therapeutic and advanced imaging trials, as well as cancer prevention and care delivery studies.

The NCI also confers recognition on cancer centers around the country, which bring together scientists and clinicians from one or more institutions in transdisciplinary efforts that focus on specific problems in cancer biology; conduct first-in-human clinical trials of promising new agents; organize multidisciplinary care teams to develop comprehensive care plans for patients; and engage the communities they serve in programs that aim to reduce cancer risk, improve cancer screening, and enhance access to quality cancer care. The clinical trials conducted by NCI-designated cancer centers, many supported by the Early Clinical Trials Network and the Specialized Programs of Research Excellence program, fill important research gaps that may not be addressed by NCTN trials or those conducted by private industry.

“As the anchor of the nation’s cancer research efforts, the National Cancer Institute is the largest public funder of cancer research in the world.”— Richard L. Schilsky, MD, FACP, FSCT, FASCO

Tweet this quote

Commercial or industry-sponsored trials are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which was created in 1906 by the Pure Food and Drugs Act. The FDA ensures that cancer therapies and diagnostic tests used as part of the care of patients with cancer are safe and effective before market entry. Contemporary cancer care involves the use of drugs and biologics, often guided by molecular tests used to identify patients most likely to benefit from treatment. In the past, the regulation of these diverse products was distributed across multiple centers, divisions, or offices of the FDA, resulting in the application of different approval standards, review processes, and timelines.

To better organize these efforts, in 2017, the FDA created the Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE), which streamlined the approval process for oncology-related drugs, biologics, and devices by bringing multidisciplinary teams together across the FDA. In addition to the FDA’s role in approving new therapies, it also grants approval for trials to begin after receiving an investigational new drug (IND) application from the trial sponsor. Better coordination of the NCI and FDA review processes is necessary to ensure that NCI-sponsored trials are launched in a timely fashion and not subject to redundant and sometimes discordant review processes; historically, such processes have contributed to trial launch times of nearly 3 years.

A 2010 report by the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) recommended the NCI coordinate with the FDA for oversight of NCI-funded trials to ensure appropriate protocol design early in the process, reducing the number of reviews and revisions that may be required. It also recommended the NCI defer review of protocols conducted under an IND to the FDA to help eliminate redundant review loops.

It is not clear to what extent these recommendations have been implemented to date. The NCI did take a major step to reduce administrative effort in protocol reviews by local independent review boards with the creation of the central institutional review board in 2001 to review late-phase oncology trials in adults; this approach may potentially replace redundant local independent review board reviews conducted at hundreds of institutions across the country and hasten the time to trial launch. Initially voluntary, participation in the NCI central institutional review board program is now mandatory, and the NCI has established 4 central independent review boards that serve more than 2,700 institutions in all 50 states and Puerto Rico.

Ensuring Access to Care for All Patients With Cancer

Scientific advances are of little benefit unless they can reach the patients who need them. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) plays an important part in enabling patient access both to approved treatments as well as clinical trials through its administration of Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Established in 1977 as the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), CMS can redesign the landscape of practice and impact delivery of care through its coverage and reimbursement decisions.

As most patients with cancer are aged 65 or older, CMS coverage decisions impact what diagnostic evaluations and treatments many patients with cancer can receive and when they can receive them, following regulatory approval. Many newly approved cancer therapeutics are expensive, and the CMS must weigh the benefit of allowing coverage and reimbursement for a drug or service, both of which are necessary for patient access to FDA-approved therapies, against the budget it has available to support the needs of all its beneficiaries.

Although the FDA standard for drug or biologic approval is that the product is “safe and effective,” the CMS applies a different standard for reimbursement: that the product is “reasonable and necessary” for use in Medicare beneficiaries, although it is unclear what criteria are applied to reach this determination. Application of these different standards requires independent review of trial data by each agency and can delay reimbursement of, and therefore access to, therapies newly approved by the FDA. Although the CMS generally covers FDA-approved drugs and devices, coverage is not automatic. Ideally, determinations of coverage and payment would happen at the same time as approval, with regulators, payers, and manufacturers engaging in discussions about clinical and cost data.

“Duplicative oversight caused by overlapping jurisdictions or lack of coordination creates obstacles for researchers and clinicians and slows progress in the delivery of quality care to patients with cancer.”— Richard L. Schilsky, MD, FACP, FSCT, FASCO

Tweet this quote

In this scenario, announcement of a new drug or device would include clear and consistent guidance on its use, and coverage and payment issues would be determined in advance. These agencies have taken some steps to increase collaboration, but more is needed. For instance, in 2010, the FDA piloted (and later made permanent) a parallel review process to shorten the amount of time between FDA product approval and CMS coverage decisions. If a manufacturer chooses this path, the CMS can review clinical data preapproval. Although a positive step, it is not clear that this process has yet resulted in a reduced timeline for introduction of many products.

Additionally, in 2019, the FDA, CMS, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced a task force representing the three agencies to enable rapid deployment of diagnostic tests in a public health emergency. By standardizing collaboration efforts through a task force, these federal partners sought to address issues related to the implementation of diagnostic tests authorized for emergency use, as well as other unmet needs and gaps in preparing and responding to global health threats, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Modeling this collaborative process could assist agencies in refining and streamlining interagency approaches to expanding access to new cancer treatments, particularly for cancers with a high unmet medical need.

Covering the Routine Costs of Clinical Trial Participation

CMS policies can also impact patient access to clinical trials. Prior to 2000, coverage of routine clinical care costs for trial participants was not provided by Medicare or Medicaid, creating a significant barrier to clinical trial participation for many individuals. A 2000 executive memorandum issued by the Clinton administration required Medicare to cover routine clinical costs associated with trial participation, and this requirement was then mandated by provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Only recently has Medicaid been required to cover these costs with the passage of the Clinical Treatment Act in late 2020.

While broadening access to clinical trials, these policies require detailed cost analyses of each trial to ensure that “research-related costs” are not inappropriately billed to federal coverage programs, and little guidance exists on how to conduct such analyses. Each institution participating in a trial repeats the process, consuming resources and potentially slowing trial launch. Clear guidance and a uniform approach to such cost analyses performed by sponsors on behalf of all trial sites would greatly alleviate these issues.

Breaking Down Research Silos

The U.S. health-care system has been criticized for not operating as a unified “system.” The foregoing offers just some of the examples that must be addressed. Duplicative oversight caused by overlapping jurisdictions or lack of coordination creates obstacles for researchers and clinicians and slows progress in the delivery of quality care to patients with cancer. That said, meaningful reform aimed at breaking down silos is possible, as demonstrated by the creation of the FDA’s OCE, which brings together scientists and clinicians with expertise in oncology drugs and devices from across the agency into a single center charged with organizing and conducting the review of all oncology products. Further innovation, including better coordination of NCI and FDA review processes for clinical trials and concurrent premarket review of safety and efficacy data by both the FDA and the CMS, is essential as we look to the future of cancer research and care in America.

Conquering Cancer

The breakthroughs that have been made against cancer provide hope for the future and fuel public expectation for a continued, steady rate of progress to conquer cancer over the coming decades. Delivering on this promise requires reexamining the structure, functions, and relationships among the federal agencies charged with supporting and overseeing the nation’s cancer care and research enterprise. In the first 50 years since the passage of the National Cancer Act of 1971, the United States built an expansive infrastructure to support cancer care and research; the next 50 years should address how best to harness all its power.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Schilsky is the principal investigator of the ASCO TAPUR study. ASCO receives research grants to support the study from the following companies: AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, and Seagen. He is also a consultant to and receives honoraria from Bryologyx, Cellworks, Clarified Precision Medicine, EQRx, Illumina, and Scandion Oncology.

Dr. Schilsky is Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago and former Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President of ASCO.

Adapted with permission from coauthors Shelagh Foster, Shimere Sherwood, and Richard L. Schilsky; Chapter 16: “US Federal Agencies: Advancing Cancer Research and Care Through Improved Coordination and Efficiency,” published in A New Deal for Cancer: Lessons From a 50 Year War (Public Affairs, 2021), and from the editors of the book, Abbe R. Gluck and Charles S. Fuchs.

Disclaimer: This commentary represents the views of the author and

may not necessarily reflect the views of ASCO or The ASCO Post.