Bookmark

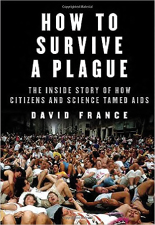

Title: How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS

Author: David France

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

Publication date: November 2016

Price: $30.00, hardcover, 640 pages

On June 5, 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) describing cases of a rare lung infection in five young gay men in Los Angeles. The men had other unusual infections as well, indicating their immune systems were compromised. The MMWR report marked the first official notice of what became known as the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic.

Over several decades, AIDS became a wrenching sociopolitical phenomenon that tested the nation’s tolerance and civil structure. It also spawned one of our most robust and star-studded advocacy movements, spearheading targeted research efforts that ushered in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

People with HIV/AIDS are at high risk for developing certain cancers, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cervical cancer. For that, and other reasons, the arc of the AIDS epidemic is inextricably linked to the oncology community. The whole social and scientific history of AIDS is told in a recently published book, How to Survive a Plague: The Inside Story of How Citizens and Science Tamed AIDS. The author, award-winning investigative reporter David France, is a gay man who moved from Kalamazoo, Michigan, to New York in 1981, the same year AIDS went public.

Masterful Writing, Meticulous Research

Arranged in 4 parts, Mr. France’s 640-page book is a masterfully written and meticulously researched history of AIDS. Written in chronologic order, the massive book becomes a slog at times, feeling like you are reading about every activist demonstration, Pharma boardroom discussion, hospital emergency room, drug trial, and congressional subcommittee hearing of the decades-long story of the AIDS epidemic. That’s where the content’s page, notes, and index come in handy; you can pick and chose the content of your choice.

The bigotry and mob mentality that poisoned the national environment were richly seized by the story of Ryan White, a 13-year-old boy with hemophilia who developed HIV through contaminated blood products during a transfusion. “Terror-stricken students and their parents forced him out of the seventh grade, demanding that he take his lessons through a telephone hookup. They shunned the rest of the family as well. When his uninfected mother, Jeanne White, went to the grocery store, cashiers would throw down her change to avoid touching her. Vandals broke the windows of the family home, slashed their car tires, and put a bullet into the living room when the family sought relief in court.”

Fast-Track Approval of Zidovudine

Mr. France is justifiably passionate but never preachy or pedantic. He also is sure-handed in explaining the science involved in the rush to find drugs to quell the epidemic and ease suffering. Readers of The ASCO Post will enjoy the section about the clinical trial led by Samuel Broder, MD, co-discoverer of zidovudine (AZT).

This is a fascinating history of desperate people who were facing a death sentence, but their unwillingness to waver forced science and society to come together, transforming human tragedy into triumph.—

Tweet this quote

Patients clamored to enroll in the phase II AZT trial, and Mr. France captures their desperation to fill 1 of the 282 spots. Most were turned away because their CD4 cell count was too high or they had Kaposi’s sarcoma. Toxicity became a problem almost immediately. After a few weeks, only about 10% of the patients remained on trial. The drama builds as Dr. Broder contemplates the need to pull the plug. He races to the hospital where then National Cancer Institute head, Vincent DeVita, MD, was recuperating after emergency surgery. They reviewed the data, and as Mr. France writes, “DeVita inhaled deeply and said, ‘We must stop the study.’” AZT had toxicity issues, no doubt, but it still was the only hope for thousands of desperate men; so, after much consideration, it was given fast-track approval.

Transforming Tragedy Into Triumph

Mr. France does a good job in toggling the medical challenges, which seemed to change weekly, along with the gay activist community’s struggle to push aside the stigma and fear associated with AIDS, and fight, literally in the streets, to stimulate research funding. In a chapter aptly titled “Warfare,” the author gives the reader a close up of the bigotry that overshadowed the human crisis of AIDS. When activists marched in New York City, they encountered vitriolic mobs. “Even near St. Patrick’s Cathedral, followers of the Reverend Jerry Falwell shouted and waved signs reading ‘Quarantine Manhattan Island, the AIDS capital of the world.’”

In the face of such ugliness, the gay activist community was unrelenting in its fight for dignity and help from a slow-moving bureaucracy, which was captured during a famous demonstration by ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). On October 11, 1988, ACT UP had one of its most successful demonstrations, when its members shut down the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a full day to protest the high price of AZT, the only drug at the time approved for AIDS. Others infiltrated the New York Stock Exchange and chained themselves to the VIP balcony. This is a fascinating history of desperate people who were facing a death sentence, but their unwillingness to waver forced science and society to come together, transforming human tragedy into triumph. How to Survive a Plague is highly recommended for readers of The ASCO Post. ■