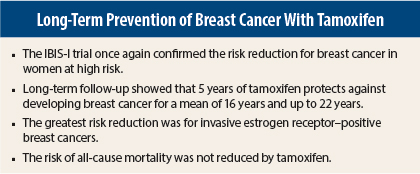

The benefits of tamoxifen as primary prevention of breast cancer are well established. The good news is that the benefits live on, with a protective effect that extends up to 22 years. At a median follow-up of 16 years, women treated with 5 years of tamoxifen enjoyed a 29% reduction in the risk of developing any type of breast cancer and a 35% reduction in the risk of developing estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer compared with placebo-treated controls. These positive results of the large International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS-I) were presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium and published online simultaneously in Lancet Oncology.1,2

“Tamoxifen is a well-established and effective treatment for certain breast cancers, but now we have evidence of its very long-term preventive benefits in women at risk for breast cancer. The preventive effect of tamoxifen is highly significant, with a reduction in breast cancer rates of around one-third, and this impact has remained strong and unabated for 20 years. We hope these results will stimulate more women, particularly younger women, to consider treatment options for breast cancer prevention if they have a family history of the disease or other risk factors,” stated lead author Jack Cuzick, PhD, of Centre for Cancer Prevention, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Queen Mary University London, United Kingdom.

Even though these long-term results are so striking, Dr. Cuzick acknowledged that we still have a lot to do to convince women at risk who are otherwise healthy to take the drug. “This has been a major issue. Cardiologists are more effective at primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. We have to find a way to make it very clear that women at high risk of breast cancer should be offered prevention. There is a misunderstanding about the side effects of tamoxifen. If a woman develops side effects, she can always stop the drug,” he said.

Closer Look at IBIS-I

IBIS-I enrolled 7,154 high-risk premenopausal and postmenopausal women from genetics clinics and breast care clinics in 8 different countries and randomized them 1:1 to receive 5 years of tamoxifen or placebo. Most of these women were deemed at high risk due to a family history of breast cancer.

The median age at study initiation was 50.8 years; during the trial, about 50% of women in the placebo group used hormone replacement therapy, compared with 41% of women in the tamoxifen group. About 35% of both groups had previous hysterectomy.

At a median follow-up of 16 years (maximum follow-up, 22 years), breast cancers were reported in 251 patients (7%) in the tamoxifen group vs 350 (9.8%) in the placebo group, a highly significant 29% reduction in risk favoring tamoxifen (P < .0001). The greatest risk reduction was observed for invasive estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, a highly significant 34% reduction (P < .0001) and ductal carcinoma in situ (35% risk reduction, P = .05). The effect on ductal carcinoma in situ was predominantly seen during the first 10 years of follow-up. However, tamoxifen did not protect against invasive estrogen receptor–negative breast cancer.

At 10 years, previous results of the trial showed that the number needed to treat with tamoxifen to prevent one case of breast cancer was 59; at 20 years, the number needed to treat to prevent one case of breast cancer was reduced to 22. The number needed to treat to prevent one case of invasive estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer was 29.

The benefits of tamoxifen were significantly greater for women who did not take hormone replacement therapy during the trial: a 38% reduction in the risk of breast cancer vs a 12% reduction in the risk for women taking hormone replacement therapy during the trial (P = .04) and a 45% risk reduction for estrogen receptor–positive breast cancers in noncurrent users of hormone replacement therapy vs 13% in current users of hormone replacement therapy (P = .03).

“This indicates the clear loss of efficacy of tamoxifen when menopausal hormone therapy is used concomitantly, and this effect needs to be studied further,” Dr. Cuzick said.

No significant difference in breast cancer prevention related to age younger or older than 50 years was observed.

Other Cancers

Over follow-up, 666 other cancers were reported: 351 (9%) in the tamoxifen group compared with 315 (8%) in the placebo group. There was a trend toward more endometrial cancers in the tamoxifen group over extended follow-up, with a total of 29 vs 20 in the placebo group; most of the endometrial cancers in the tamoxifen group occurred over the first 5 years, when patients were on active treatment.

Nonmelanoma skin cancers were also increased in the tamoxifen group: 116 compared with 84 in the placebo group (P = .022). Gastrointestinal cancers were decreased in the tamoxifen group: 42 compared with 63 in the placebo group.

Causes for Concern

The reduction in the incidence of breast cancer with tamoxifen did not translate into a mortality reduction or a reduction in breast cancer mortality at 20 years. A nonsignificant numerical incidence in endometrial cancer deaths was reported in the tamoxifen group: 5 vs 0.

“Clearly, the lack of a mortality benefit and the slight increase in endometrial deaths are concerns,” Dr. Cuzick said. “The number of deaths is still small compared with the number of breast cancer cases, which is 10 times higher. We will continue to monitor these women for another decade to gain a better understanding of the impact of tamoxifen on death rates. Some of the side effects of tamoxifen are also cause for concern and require continued monitoring, specifically endometrial cancer.”

A Glimpse at IBIS-II Results

IBIS-II trial results, presented in 2013 and published in 2014,3 showed that 5 years of anastrozole reduced the risk of developing breast cancer in at-risk postmenopausal women by 53%, a greater magnitude of benefit than is seen with tamoxifen. Dr. Cuzick said that an aromatase inhibitor such as anastrozole or exemestane should be the drug of choice in postmenopausal women and that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence was currently considering including the aromatase inhibitors anastrozole and exemestane in clinical guidelines for breast cancer prevention in postmenopausal women.

“For most premenopausal high-risk women, tamoxifen remains the only choice for breast cancer prevention, and it is a good one—as shown by the IBIS-I evidence,” he concluded. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Cuzick is on the speakers bureau for AstraZeneca.

References

1. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cawthorn S, et al: 16 year long-term follow-up of the IBIS-I breast cancer prevention trial. 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Abstract S3-07. Presented December 11, 2014.

2. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cawthorn S, et al: Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. December 10, 2014 (early release online).

3. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al: Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): An international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 383:1041-1048, 2014.