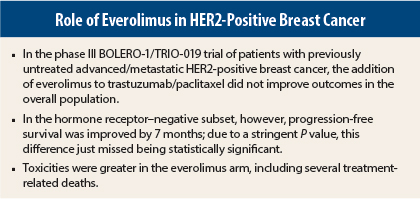

The addition of everolimus (Afinitor) to weekly trastuzumab (Herceptin) plus paclitaxel in the first-line metastatic breast cancer setting did not improve outcomes in the phase III BOLERO-1/TRIO-019 but did provide a “signal” in the hormone receptor–negative subset. The study was reported at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium by Sara A. Hurvitz, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.1

“The study did not meet its objective in the full population,” Dr. Hurvitz reported, but it did show an “interesting” benefit in hormone receptor–negative patients.

The data validate preliminary observations from other studies that the treatment effect of everolimus differs based on hormone receptor expression in patients with HER2-positive advanced breast cancer in the absence of hormonal therapy, she said.

BOLERO-1 was based on the concept of countering treatment resistance by inhibiting the mTOR pathway in early metastatic disease. In the previously reported BOLERO-3 trial, everolimus added to trastuzumab and vinorelbine significantly improved progression-free survival for patients with trastuzumab-resistant previously treated cancer.2

“We were interested in evaluating whether inhibiting mTOR early in metastatic disease will help delay the development of resistance to HER2-targeted therapy,” she said.

BOLERO-1/TRIO-019 Study

The study enrolled 719 patients with locally advanced or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer and no prior treatment in this setting. They were randomly assigned 2:1 to everolimus (10 mg/d) plus paclitaxel and trastzumab or paclitaxel/trastuzumab alone, until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed progression-free survival in the whole population and in the hormone receptor–negative subpopulation. Overall survival was a secondary endpoint.

In the full study population, progression-free survival was comparable between the arms: 14.95 months with the addition of everolimus and 14.49 months with placebo (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.89, P = .1166). In the hormone receptor–negative subpopulation, however, everolimus-treated patients achieved a median progression-free survival of 20.27 months, vs 13.08 months with placebo (HR = 0.66, P = .0049), Dr. Hurvitz reported.

“We saw a 7-month improvement favoring the everolimus arm, and while this was intriguing, it did not meet the prespecified level of significance (P < .0044),” she reported.

Everolimus-Related Toxicities

Adverse events were similar to those seen in BOLERO-3. Patients treated with everolimus had more stomatitis (67% vs 32%) and diarrhea (56% vs 47%), which were the most common adverse events in this arm, along with alopecia (47% vs 53%). Suspected drug-related serious adverse events were reported for 22% of the everolimus arm vs 8% of the control arm.

There were also several adverse event–related, on-treatment deaths in the everolimus arm (3.6%), due to pneumonitis, pulmonary embolism, respiratory failure, pulmonary edema, pneumonia, and cardiorespiratory arrest, and none in the control arm. Only one of these occurred, however, after clinicians undertook more proactive management of toxicities.

“The deaths may be associated with a lack of experience in managing adverse events related to everolimus when combined with chemotherapy, as there was a higher rate of on-treatment deaths in regions with limited experience with the drug. In some cases, protocol-defined adverse event management guidelines were not followed,” Dr. Hurvitz indicated.

“Safety was consistent with the known safety profile from BOLERO-3, but the increased rate of adverse event–related on-treatment deaths underscores the need for proactive, aggressive management of adverse events when combining everolimus with chemotherapy,” she emphasized.

Retrospective Considerations

The benefit in the previous BOLERO-3 trial was also predominantly observed in the hormone receptor–negative subset. “Had we known about this [hormone receptor]-negative signal from the start, we might have done this trial in a [hormone receptor]-negative population or enrolled more [hormone receptor]-negative patients,” she said. This could have given BOLERO-1 more power to show a benefit, at least in a certain subpopulation of HER2-positive patients.

“We came so close to meeting the prespecified level of significance. We set the bar high for the [hormone receptor]-negative subset because we wanted to heavily favor the full population so we would not miss a signal,” she explained. “We are all thinking about this now and asking whether future studies should be planned in the [hormone receptor]-negative subset.”

Additional discussion about the BOLERO-1 design revolved around the lack of an endocrine therapy arm for the HER2-positive patients. The design was predicated on previous studies showing that progression-free survival and response rates associated with the combination of endocrine and anti-HER2 agents are “relatively low,” and therefore, “we felt it was ethical to use chemotherapy with trastuzumab and everolimus,” she said.

‘Escape Mechanism’

C. Kent Osborne, MD, Director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, elaborated on this point. “Based on studies done with tamoxifen 20 years ago, we learned it’s not good to give tamoxifen with chemotherapy, and we extrapolated that to all endocrine therapies—that we should not give them at the same time as chemotherapy. I suspect that’s wrong, since other endocrine therapies work by different mechanisms, and trials are now looking at adding other endocrine therapies like an aromatase inhibitor with chemotherapy,” he said.

“This is important because the estrogen receptor (ER) provides an escape mechanism that can cause resistance to HER2-targeted therapy. If you don’t block ER in an ER/HER2-positive tumor, the estrogen receptor can provide alternative signals for the cells to survive,” he explained.

The latest studies are examining different combinations in HER2-positive, ER-positive advanced breast cancer. NCT02152943 is evaluating everolimus, letrozole, and trastuzumab, and NCT01791478 is testing a PI3K inhibitor (BYL719) plus letrozole and trastuzumab. NSABP B52 is testing whether letrozole can be added to chemotherapy and dual HER2-targeted therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer.

Dr. Osborne also suggested that the effect of everolimus might have been obscured by the use of paclitaxel, which inhibits tumors with PI3K alterations. He suggested it would be interesting to study trastuzumab plus everolimus without chemotherapy, “to get a better indication of whether you are reversing a component of HER2 therapy resistance.” n

Disclosure: Dr. Hurvitz has received research funding from Novartis, Genentech, and Roche (paid to UCLA) and travel reimbursement from Novartis and Genetech. Dr. Osborne has served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and NanoString in the past year.

References

1. Hurvitz SA, Andre F, Jiang Z, et al: Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of daily everolimus plus weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel as first-line therapy in women with HER2+ advanced breast cancer. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Abstract S6-01. Presented December 12, 2014.

2. André F, O’Regan R, Ozguroglu M, et al: Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3). Lancet Oncol 15:580-591, 2014.