At the 2011 Pan-Pacific Lymphoma Conference held recently in Kauai, Hawaii, Andrew M. Evens, DO, MSc, Director of the Lymphoma Program at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, discussed Hodgkin lymphoma in elderly patients.

Event-free survival and overall survival rates in older patients with Hodgkin disease have been reported at 40% to 50% lower than rates in younger patients. This difference in outcome may be related to several factors. The disease may have a different biology in older patients, who have a greater frequency of mixed cell disease and Epstein-Barr virus–related disease.

Older patients have a greater frequency of comorbidities that preclude appropriate treatment and thus frequently have inadequate treatment duration and intensity. They also have an increased frequency of treatment-related toxicities—especially bleomycin lung toxicity.

Older patients have a greater frequency of comorbidities that preclude appropriate treatment and thus frequently have inadequate treatment duration and intensity. They also have an increased frequency of treatment-related toxicities—especially bleomycin lung toxicity.

Currently, there is no standard treatment for older patients with Hodgkin disease—ie, those aged 60 years or older. Further, these patients are underrepresented in clinical trials, typically accounting for less than 5% to 10% of most clinical trial populations, compared with 15% to 20% of the Hodgkin disease population.

Chicago Cohort

A recent retrospective analysis defined characteristics and outcomes among 95 Chicago area Hodgkin lymphoma patients over 60 years old seen between 2000 and 2010.1 Patients had a median age of 67 years, with 33% older than 70 years and 7% older than 80 years. Disease types were nodular sclerosis in 47%, mixed cell in 31%, not otherwise specified in 16%, lymphocyte predominant in 5%, and lymphocyte depleted in 1%.

Prior malignancy was present in 27% of patients, B symptoms in 54% (> 10% weight loss in 35%), ECOG performance status > 1 in 27%, stage III/IV disease in 65% (with bone marrow involvement in 25%), bulky disease in only 4%, and International Prognostic Score of 4 to 7 in 58%. With regard to functional status, 61% had a grade 3 or 4 comorbidity on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics, 26% were categorized as “not fit,” 13% had loss of activities of daily living, and 17% had a documented geriatric syndrome.

The overall response rate to treatment in this cohort of patients was 85%, with 73% having complete response. However, the 5-year event-free survival rate was 47% and 5-year overall survival rate was 58%, with rates being significantly lower in patients with stage III/IV disease than in those with stage I/II disease (37% vs 65%, respectively, for 5-year event-free survival, P = .007; 46% vs 79%, respectively, for 5-year overall survival, P = .001).

Bleomycin lung toxicity occurred in 32% of patients, which had a mortality rate of 25%. On univariate analysis, predictors of inferior event-free and overall survival were age greater than 70 years, B symptoms, weight loss, performance status > 1, low serum albumin, history of coronary artery disease, stage III/IV disease, any comorbidity of grade 3 or 4, and loss of activities of daily living. On multivariate analysis, predictors of poorer outcome were age greater than 70 years (HR = 2.24; P = .02), loss of activities of daily living (HR = 2.71, P = .04), and lack of complete response (HR = 8.1, P < .0001).

Another study has indicated some “catch up” in 10-year relative survival among elderly patients over the past 30 years.2 Compared with the period of 1980 to 1984, 10-year relative survival during 2000 to 2004 has increased by 23% among patients aged 60 years or older and by 25% in those aged 45 to 59 years. However, the gap between older and younger patients still persists, with a strong age gradient in 10-year relative survival during the 2000 to 2004 period being observed: 93% for the 15 to 24 year age group, 89% for the 25 to 34 year group, 85% for the 35 to 44 year group, 76% for the 45 to 54 year group, and 45% for the 60 year and older group.

ABVD and Stanford V in Intergroup E2496

The recent Intergroup E2496 trial compared standard Hodgkin lymphoma treatment consisting of six to eight cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; n = 404) vs 12 weeks of the Stanford V regimen (doxorubicin, vinblastine, mechlorethamine [Mustargen], etoposide, bleomycin, vincristine, and prednisone; n = 408) in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma.3 Modified involved-field radiation therapy of 36 Gy was given to patients in the ABVD group with massive mediastinal disease and to patients in the Stanford V group with affected sites > 5 cm.

A total of 43 patients aged 60 years or older were included in the trial. Compared with younger patients, these older patients were significantly less likely to have a performance status of 0 vs 1 to 2 (odds ratio = 2.58, P = .004) and significantly more likely to have the mixed cell disease type (odds ratio = 3.51, P = .0004).

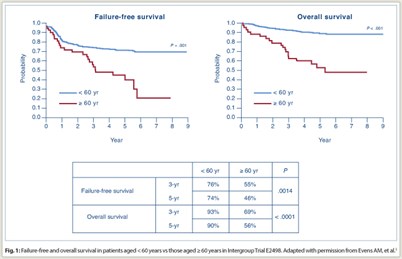

Overall response rate was 70% in older patients vs 78% in younger patients (P = .19). Rates of complete response plus clinical complete response were 65% vs 71% (P = .49). Among elderly subjects, there were no significant differences between ABVD and Stanford V in failure-free survival or overall survival. Overall, survival was significantly poorer for elderly vs younger patients (Fig. 1): 3-year failure-free survival was 55% vs 76% (P = .0014) and 5-year failure-free survival was 46% vs 74% (P < .0001); 3-year overall survival was 69% vs 93% (P < .0001) and 5-year overall survival was 56% vs 90% (P < .0001).

Overall response rate was 70% in older patients vs 78% in younger patients (P = .19). Rates of complete response plus clinical complete response were 65% vs 71% (P = .49). Among elderly subjects, there were no significant differences between ABVD and Stanford V in failure-free survival or overall survival. Overall, survival was significantly poorer for elderly vs younger patients (Fig. 1): 3-year failure-free survival was 55% vs 76% (P = .0014) and 5-year failure-free survival was 46% vs 74% (P < .0001); 3-year overall survival was 69% vs 93% (P < .0001) and 5-year overall survival was 56% vs 90% (P < .0001).

Among older patients, grade 3 nonhematologic toxicity with ABVD occurring in more than 5% of patients consisted of fatigue in 17% and dehydration, vomiting, hyperglycemia, and myalgia in 9% each; grade 4 toxicities consisted of motor neuropathy and sensory neuropathy in 9% each and neutropenic fever in 4%. Grade 3 toxicities occurring in more than 5% of patients receiving Stanford V consisted of motor neuropathy in 15% and muscle weakness, hyperglycemia, and neutropenic fever in 10%; grade 4 toxicities consisted of constipation and myalgia in 5% each.

Overall treatment-related mortality was significantly greater in older vs younger patients (9.3% vs 0.3%, P < .001). Bleomycin lung toxicity occurred in 26% of older patients (n = 11), with a fatality rate of 18%. Of these 11 cases, 10 were in the ABVD group.

Analysis of German Hodgkin Study Group Trials

Similar disparity in outcome was observed in the analysis of elderly patients who were treated in the German Hodgkin Study Group trials for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. The HD10 trial comparing two vs four cycles of ABVD plus radiotherapy of 20 or 30 Gy included 68 elderly patients, and the HD11 trial comparing ABVD vs BEACOPP-baseline (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine [Matulane], and prednisone) plus radiotherapy of 20 or 30 Gy included 49 elderly patients (median ages of 65 and 64 years, respectively).

WHO grade 3/4 toxicities occurred in 67% of these patients in HD10 and in 69% in HD11. Treatment-related mortality was 5%. Furthermore, the 5-year progression-free survival rates for elderly vs younger patients with Hodgkin lymphoma were 79% vs 96% in HD10 and 69% vs 86% in HD11.4

Current and Future Directions

The UK SHIELD (Study of Hodgkin lymphoma In the Elderly/Lymphoma Database) program has allowed physicians to treat elderly patients through a phase II study protocol using VEPEMB therapy (vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, etoposide, mitoxantrone, and bleomycin) or to collect data from elderly patients otherwise under treatment. More than 200 patients were registered in the program. Data collection included comorbidity and functional scales and quality-of-life assessments. Analyses of these data are expected in the near future.

In the United States, a phase II study is underway to examine incorporation of brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) and positron-emission tomography (PET) into front-line treatment of advanced disease in patients aged 60 years or older.5 Brentuximab vedotin is a CD30-directed antibody-drug conjugate that was recently approved for treatment of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous stem cell transplantation or after failure of at least two prior multiagent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not stem cell transplant candidates.

Following PET and computed tomography (CT) staging, patients will receive two cycles of brentuximab vedotin at 1.8 mg/kg every 3 weeks, followed by PET in the first 22 patients. Patients with complete response, partial response, or stable disease will then receive six cycles of AVD (doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine). Those with complete or partial response on subsequent PET and CT are to receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin at the same dose for four cycles. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Evens has received research funding from Seattle Genetics.

Expert Point of View: Therapy for Hodgkin Lymphoma in the Elderly Remains Undefined

References

1. Evens AM, Helenowski I, Ramsdale E, et al: A retrospective multicenter analysis of elderly Hodgkin lymphoma: Outcomes and prognostic factors in the modern era. Blood November 23, 2011 (early release online).

2. Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D: Ongoing improvement in long-term survival of patients with Hodgkin disease at all ages and recent catch-up of older patients. Blood 111:2977-2983, 2008.

3. Evens AM, Hong F, Gordon LI, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of ABVD and Stanford V for elderly advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (HL): Analysis from the phase III randomized U.S. Intergroup Trial E2496. J Clin Oncol 29(suppl):Abstract 8035, 2011.

4. Böll B, Görgen H, Fuchs M, et al: Feasibility and efficacy of ABVD in elderly Hodgkin lymphoma patients: Analysis of two randomized prospective multicenter trials of the German Hodgkin Study Group (HD10 and HD11). Blood 116(21):Abstract 418, 2010.

5. ClinicalTrials.gov: Brentuximab vedotin and combination chemotherapy in treating older patients with previously untreated stage II-IV Hodgkin lymphoma. Available at: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01476410.