Members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning, intersexed (LGBTQI+) community face numerous challenges and barriers when accessing the health-care system in the United States, including cancer care; as a result, they may be at greater risk for developing cancer and experiencing worse outcomes compared with heterosexual patients. According to the results from the 2013–2016 National Health Interview Survey, which examined cancer diagnoses between 129,431 heterosexual adults and 3,357 lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults, gay men had more than 50% increased odds of reporting a cancer diagnosis compared with heterosexual men. Similarly, bisexual women had 70% increased odds of reporting a diagnosis of cancer compared with heterosexual women.1 LGBTQI+ individuals are also at an elevated risk for specific types of cancer, including lung, anal, breast, cervical, colorectal, endometrial, and prostate.2

“Our cancer journeys are not going to match other people’s cancer journeys, and we need providers to be aware of our concerns, so we can have a high-quality life after cancer.”— NFN Scout, PhD, MA

Tweet this quote

In addition to cancer, LGBTQI+ persons often contend with other serious health risks, including depression, anxiety, suicide, and substance abuse. Furthermore, lesbian and bisexual women are more likely to have obesity than heterosexual women.2

The reasons for health-care disparity in this population are many, including societal stigma and discrimination, lack of health insurance, and providers’ lack of knowledge about their health-care needs. As a result, many LGBTQI+ individuals delay or forgo seeking medical care because of concerns about how they will be treated.3

GUEST EDITOR

Karen M. Winkfield, MD, PhD

The Diversity in Oncology column addresses the inequities in cancer care for minority racial, ethnic, and LGBTQI+ populations and is guest edited by Karen M. Winkfield, MD, PhD, Executive Director of the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance; Ingram Professor of Cancer Research; and Professor of Radiation Oncology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center; and Chair of ASCO’s Workforce Diversity Taskforce.

Although the exact number of people in the United States who are part of a sexual or gender minority is not known due to insufficient demographic data collection on this population in the U.S. Census (questions about sexual orientation and gender identity were added to the most recent survey in 2021), a recent Gallup poll found that 5.6% of adults in the United States identify as LGBTQI+.4 And although national cancer registries, including the National Cancer Database, do not routinely collect sexual orientation or gender identification cancer surveillance public health information, estimates are that more than one million LGBTQI+ individuals are living with cancer.5

Identifying Welcoming Oncology Practices

The recent publication of OUT: The National Cancer Survey by the National LGBT Cancer Network (https://cancer-network.org/out-the-national-cancer-survey/) is shedding light on how cancer affects this underserved patient population. The Web-based survey was conducted between September 2020 and March 2021 and was open to individuals who self-identify as LGBTQI+, were previously diagnosed with cancer, and live in the United States. More than 2,700 LGBTQI+ cancer survivors responded to the survey. The vast majority, 60%, self-identified as male; 32% as female; 3% as transgender; 2% as genderqueer/gender nonconforming; 2% nonbinary; and 1% as another gender identity; were mostly White, 85%; and had a median age of 59.

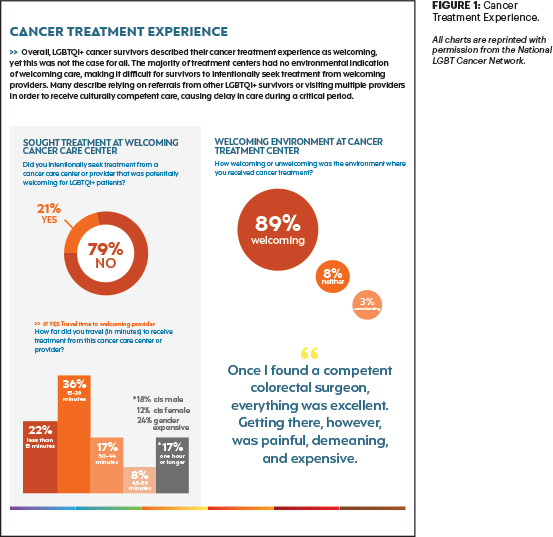

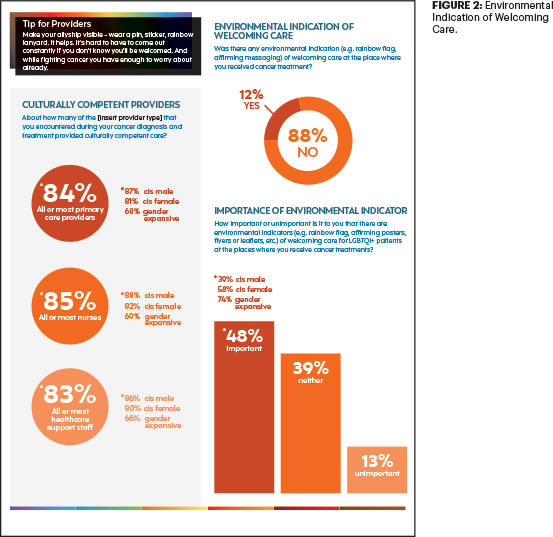

There were many positive responses in the survey regarding cancer survivors’ treatment experience, with 89% saying their experience at their cancer treatment center was “welcoming.” However, nearly the same majority, 88%, said there was no environmental indication, such as a rainbow flag or affirming message, of welcoming care6 (Figures 1 and 2).

“Once I found a competent colorectal surgeon,” wrote one respondent, “everything was excellent. Getting there, however, was painful, demeaning, and expensive.”

The overwhelming majority of respondents, 92%, were satisfied with their overall cancer treatment experience. However, one respondent commented: “I wish my urologist had given me fertility options and told me I would never be able to ejaculate again.”

“More people are reporting being welcomed in cancer care, but the welcoming is often more arduous for us, so when that journey is as time-sensitive as a cancer diagnosis and treatment, we don’t want people to have to take extra steps,” said NFN Scout, PhD, MA, Executive Director of the National LGBT Cancer Network and a principal investigator of OUT: The National Cancer Survey. “We want LGBTQ patients to be able to go to their local cancer center and have that be the end of their shopping for a welcoming provider.”

The ASCO Post talked with Dr. Scout about the respondents’ experience in accessing cancer care and how to ensure that LGBTQI+ survivors have a high-quality of life after cancer.

Interpreting Survey Findings

Many of the findings in the survey were contrary to what statistics generally show about the LGBTQI+ community, including that many do not have health insurance. In your survey, nearly all respondents, 97%, said they have health insurance. And although another large majority, 81%, said their cancer diagnosis was given in a “respectful” manner, one respondent commented that his “surgeon said he had good news and bad news. Bad news: you have cancer. Good news: you don’t have much hair to lose.”6 How do you interpret the findings in your survey?

I agree there were some very positive datapoints in the survey that are contrary to what other statistics show regarding these issues. I am always a little suspicious when I see these kinds of percentages, because populations that are discriminated against tend to underexpress some of their health challenges, so I’m a little cautious about some of our findings.

For example, although 86% of respondents said they do not currently use

tobacco products, more than half, 53% said they have smoked cigarettes in their lifetime, and that’s a pretty high percentage. We must remember that a piece of the discrepancy has to do with the fact that all of our respondents have had a life-threatening health scare, so what they may be doing now to improve their health may be different from what they were doing before their cancer diagnosis.

Although the vast majority, 89%, said they felt welcomed at their cancer treatment center, only 12% said there was a physical indication, such as a rainbow flag, to indicate a welcoming environment.

Our survey was overrepresented by cisgender White men, and that is likely to be one of the more stable populations in the queer community, which may explain these findings.

Revealing Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity to Providers

Three-quarters of the respondents said they self-disclosed their LGBTQI+ identity during their medical consultation. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, many health-care providers do not routinely discuss sexual orientation or gender identity with their patients, and many health-care facilities do have not systems in place to collect such data.7 Please talk about the need to have a standard patient intake form that includes questions about sexual orientation or gender identity.

One of the many lessons we learned from the COVID-19 pandemic is how the coronavirus disproportionately impacts racial and ethnic populations. However, there is no data collection on how the virus is impacting the LGBTQI+ population. It is the same with cancer incidence. We do not know how many LGBTQI+ individuals have cancer because there are no questions about sexual or gender identity on patient intake forms.

I don’t know what the cancer incidence is among this community, because, unfortunately, we are being forced into the closet by the medical establishment. Although our survey and others show a large majority of us are willing to disclose our sexual orientation status, a similarly large majority of physicians do not feel comfortable or that it is appropriate to ask patients about their sexual identity.

We need to close this education gap, because we are more willing to disclose our status than providers assume. There is no need to be hesitant about including these questions on patient intake forms.

Providing a Tailored-Care Approach for Patients

Although a vast majority of respondents, 92%, said they were satisfied with the treatment they received, 82% said they were never given information about their fertility options. Did the survey ask about whether oncologists provided information about their treatment’s potential side effects?

We did not ask questions specific to treatment side effects, but we do know there is a heteronormative world view. Misunderstanding how sex is different for queer people is a challenge, particularly for patients with genital or anal cancer, as well as breast cancer. We hear stories about lesbian women with breast cancer being pushed toward breast reconstruction after a mastectomy when they have absolutely no interest in the surgery and would prefer “going flat.” Many people presume we are engaging in heterosexual sex, and that is the only information they have to give you, but that is absolutely useless to us.

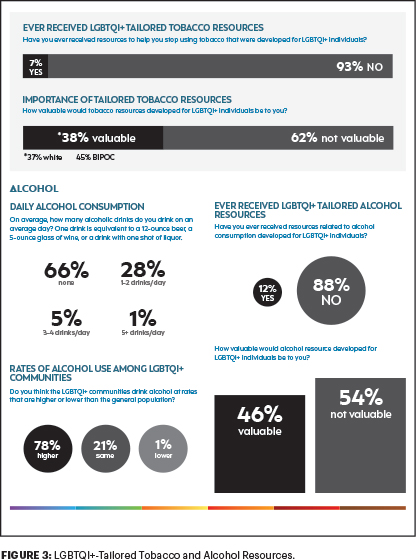

Previous research has found that many health-risk behaviors, including tobacco and alcohol use, are higher among the LGBTQI+ community. Yet only a small number of our respondents, just 7%, said they received LGBTQI+-tailored tobacco resources to help them stop smoking; and only 12% received LGBTQI+-tailored alcohol resources (Figure 3).

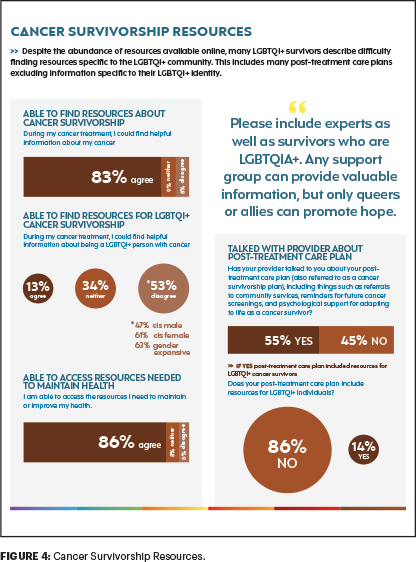

Our cancer journeys are not going to match other people’s cancer journeys, and we need providers to be aware of our concerns, so we can have a high-quality life after cancer (Figure 4). We must move away from the one-size-fits-all approach to cancer care. We know from patient-centered medicine that if we have a better experience with our providers, we have a better health outcome. So, it’s not just about ordering the right tests or the right chemotherapy that makes the difference in outcome. It’s the relationship physicians build with their patients that helps a better outcome. That is where providers must do a better job in caring for LGBTQI+ patients with cancer.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Scout reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Gonzales G, Zinone R: Cancer diagnosis among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Results from the 2013–2016 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Causes Control 29:845-854, 2018.

2. Tamargo CL, Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, et al: Cancer and the LGBTQ population: Quantitative and qualitative results from an oncology providers’ survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors. J Clin Med 6:93, 2017.

3. Human Rights Watch: “You Don’t Want Second Best”: Anti-LGBT Discrimination in US Health Care. Available at www.hrw.org/report/2018/07/23/you-dont-want-second-best/anti-lgbt-discrimination-us-health-care#. Accessed February 2, 2022.

4. Jones JM: LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup, 2021. Available at https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx. Accessed February 2, 2022.

5. Haviland K: Training essential to understand cancer risks, address barriers facing LGBTQ individuals. HemOnc Today. November 10, 2020. Available at www.healio.com/news/hematology-oncology/20201110/training-essential-to-understand-cancer-risks-address-barriers-facing-lgbtq-individuals. Accessed February 2, 2022.

6. National LGBT Cancer Network: OUT: The National Cancer Survey. Available at https://cancer-network.org/out-the-national-cancer-survey/. Accessed February 2, 2022.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Collecting Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Information: Importance of the Collection and Use of These Data. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/transforming-health/health-care-providers/collecting-sexual-orientation.html. Accessed February 2, 2022.

Dr. Scout has faculty appointments at both Brown University and Boston Universities’ Schools of Public Health. He is a member of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Council of Councils, the Co-Chair of the NIH Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office Work Group, on the Advisory Panel for NIH’s All of Us initiative, and a U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention delegate.