The ASCO Post is pleased to continue this occasional special focus on the worldwide cancer burden. In this issue, we feature a close look at the cancer incidence and mortality rates in Kenya. The aim of this special feature is to highlight the global cancer burden for various countries of the world. For the convenience of the reader, each installment will focus on one country from one of the six regions of the world as defined by the World Health Organization (ie, Africa, the Americas, Southeast Asia, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific). Each section will focus on the general aspects of the country followed by the current and predicted rates of incidence and cancer-related mortality. It is hoped that through these issues, we can increase awareness and shift public policy and funds toward proactively addressing this lethal disease on the global stage.

Kenya is a middle-income Eastern African country with the equator passing almost through its center. It has an ethnically diverse population of 54.7 million (Table 1). Decades of high fertility and reductions in mortality among those younger than age 5 has resulted in a large youth population in Kenya, such that more than 40% of Kenyans are younger than age 15. The remaining majority are between 15 and 64 years old, and less than 4% are older than age 65.1

The national health-care budget has staggered between 5.5% and 9.5%.2 This is lower than the target of 15% set forth in the Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSP) 2013–20173 and the Abuja declaration.4 In Kenya, nearly 23% of sick patients do not seek health care due to several barriers, including high costs, the need to travel long distances, and a lack of health-care literacy.5,6 The Kenya Household Health Expenditure and Utilization Survey and World Bank data reveal that nearly 1 million Kenyans fall below the poverty line due to health-related expenditures.6

Cancer Profile

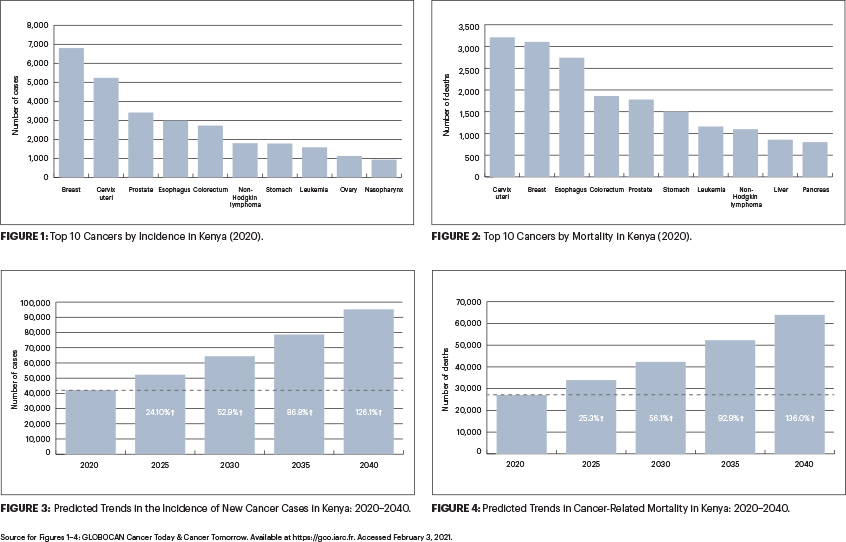

In Kenya, cancer is the third leading cause of death after infectious and cardiovascular diseases. From 2012 to 2018, the annual incidence of cancer increased from 37,000 to 47,887 new cases.7 During the same period, annual cancer mortality rose almost 16%, from 28,500 to 32,987 cancer-related deaths. The number of new cancer cases is expected to rise by more than 120% over the next 2 decades.7,8

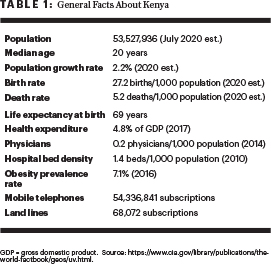

The five most common cancers in Kenya are breast, cervical, prostate, esophageal, and colorectal (Figure 1). The leading cause of cancer death in Kenya is cervical, followed by breast, esophageal, colorectal, and prostate cancers (Figure 2).8

The rising incidence of cancer, especially in aging populations, may be attributed to an increase in life expectancy combined with the adoption of unhealthy lifestyles. They include a combination of unhealthy dietary habits, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, and lack of physical exercise. An improvement in the diagnostic capabilities for detecting cancer may also have contributed to the increased incidence of the disease.9

Cancer Control Initiatives

The government of Kenya has launched many initiatives to address this rising cancer burden. In July 2020, the Ministry of Health launched the New Cancer Control Strategy, a national effort to address the growing burden of the disease in the country.7 The ministry also proposed a nationwide lifestyle modification campaign and prioritized efforts to increase awareness about cancer.7 In addition, it launched the Breast Health Awareness Campaign Pilot Report and undertook deliberate efforts to improve access to cancer care. Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Kenya, with an annual incidence of 6,000 new cases and 2,500 cancer-related deaths.9

The Ministry of Health established 10 fully functional county-level chemotherapy centers. Chemotherapy is available in several county referral hospitals located in Mombasa, Kisumu, Kakamega, Garissa, Nyeri, Nakuru, and Meru. In addition, it provided diagnostic equipment to some counties that included x-ray, computed tomography, ultrasonography, and mammography. The Ministry is currently in the process of establishing radiotherapy centers at several hospitals, including The Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, Kenyatta University Teaching Referral and Research Hospital, Nakuru County Referral Hospital, Mombasa County Referral Hospital, Garissa County, and Kisii County.

Screening for some other cancers is also available. Annual cervical cancer screening services are available in level 3 to level 6 health facilities, and all eligible women are encouraged to visit their nearest health facility (level 3 health facilities include health centers, as well as maternity and nursing homes; level 4 facilities include subcounty hospitals [in the past referred to as district hospitals] and medium-sized private hospitals; level 5 facilities include county referral hospitals and large private hospitals [in the past, referred to as provincial/regional hospitals]; and level 6 facilities include national referral hospitals and large private teaching hospitals).

In addition, patients with an established diagnosis of cervical cancer are encouraged to bring their daughters aged 10 years or older to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine. Despite high awareness, the uptake of cervical cancer screening was as low as 16%, and that of breast cancer was 12%.10,11

Screening for colorectal cancer is available at level 5 and 6 facilities. The Ministry of Health has also developed and disseminated the National Cancer Screening Guidelines to all of the country’s 47 counties.

Barriers to Cancer Control

Cancer control in Kenya, however, is hampered by several factors, ranging from an inadequate cancer care infrastructure (mainly due to financial constraints) and limited specialized human resource capacity to delayed presentation and a lack of awareness.12 There is, generally, a low level of awareness about cancer in the general population and among health-care providers, including its risk factors and common prevention and control strategies.13-15 A study in rural Kenya showed that, although more than 80% of respondents had heard of breast cancer, fewer than 10% of women and male heads of households had knowledge of two or more of its risk factors.16

In addition to the lack of awareness, there are several noted gaps in the implementation of the proposed well-intentioned policies for cancer prevention. These gaps include inadequate financing for cancer services, inappropriate use of human resources, limited research and data to support policy formulation, and the concentration of cancer services in urban areas.17,18

Inadequate funding to support cancer care services is one of the biggest obstacles to successful outcomes. Kenya has been unsuccessful in its attempts to roll out universal health coverage for all. Data from the latest government economic survey suggest that almost 80% of the population is not covered by any health insurance plan, public or private.19

The state-run National Hospital Insurance Fund provides only 25,000 Kenyan shillings (equivalent to $250 USD) per patient toward cancer care, whereas cancer treatments usually tend to cost much more than the allotted amount. Most patients end up relying on community fundraising from friends, family, and well-wishers to cover the high costs of treatment, and some forgo treatment altogether.

Finally, a significant number of patients are unable to complete the prescribed full course of treatment due to personal financial bankruptcy. For this reason, some feel that funds should be prioritized for cancers with good outcomes (eg, breast and colon) with judicious use of funds for advanced cancers with poor outcomes (eg, esophageal and pancreatic).

Further Efforts to Improve Cancer Care

Some relief for patients with cancer seeking treatment in the public institutions is provided through special treatment programs organized through public-private partnerships. An example of this is the partnership established between the Ministry of Health and Roche in 2016, which offers free treatment for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer.20 This partnership also provides training scholarships for health-care workers interested in oncology.

The Nairobi Hospital, in partnership with Kenyatta National Hospital, offers pro bono radiation therapy and chemotherapy for patients with cancer. Similarly, the partnership between Mombasa Cement and Coast Provincial General Hospital (through establishment of a chemotherapy ward) is another noteworthy example seeking to improve cancer care. These public-private partnerships can go a long way to assist the government in addressing the rising cancer burden in Kenya.

Some of the recommended policy actions to support timely cancer testing and treatment include focusing on financing insurance and human resources, increasing stakeholder engagement, decentralizing cancer services, improving cancer surveillance and data at the county level, and using the meager resources available to achieve the best results.21 It is hoped that, through these concerted efforts and by the involvement of the various entities, Kenya can be prepared to tackle the rising cancer burden (Figures 3 and 4).

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Jani, Ms. Craig, and Dr. Rooprai reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Are is a board member with Global Laparoscopy Solutions, Inc; has received research funding from Pfizer; and has a patent with the University of Nebraska Medical Center for a laparoscopy instrument.

REFERENCES

1. Wiesmann UM, Kiteme B, Mwangi Z (eds): Socio-economic atlas of Kenya: Depicting the national population census by county and sub-location. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Centre for Training and Integrated Research in ASAL Development, Centre for Development and Environment; 2014.

2. Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health: National and County Health Budget Analysis, FY 2019/20. August 2020. Available at http://www.healthpolicyplus.com/ns/pubs/18441-18797_KenyaBudgetAnalysis.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2021.

3. Republic of Kenya, Ministries of Medical Services and Public Health & Sanitation: Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSPI) July 2013-June 2017. Available at https://www.who.int/pmnch/media/events/2013/kenya_hssp.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2021.

4. World Health Organization: The Abuja declaration: Ten years on. Available at https://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/abuja_declaration/en. Accessed February 3, 2021.

5. Turin DR: Health care utilization in the Kenyan health system: Challenges and opportunities. Inquiries Journal 2(9):1, 2010.

6. Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health: Kenya Household Health Expenditure and Utilization Survey. Available at https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/745_KHHUESReportJanuary.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2021.

7. Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health: National Cancer Control Strategy 2017–2022, 2017. Available at https://www.iccp-portal.org/system/files/plans/KENYA%20NATIONAL%20CANCER%20CONTROL%20STRATEGY%202017-2022_1.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2021.

8. International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organization: Globocan 2020. Available at gco.iarc.fr. Accessed February 3, 2021.

9. Republic of Kenya, Ministry of Health: CS Health Kenya inaugurates board to fight cancer menace. July 31, 2019. Available at https://www.health.go.ke/cs-health-kenya-inaugurates-board-to-fight-cancer-menace. Accessed February 3, 2021.

10. Ng’ang’a A, Nyangasi M, Nkonge NG, et al: Predictors of cervical cancer screening among Kenyan women: Results of a nested case-control study in a nationally representative survey. BMC Public Health 18(suppl 3):1221, 2018.

11. Antabe R, Kansanga M, Sano Y, et al: Utilization of breast cancer screening in Kenya: What are the determinants? BMC Health Serv Res 20:228, 2020.

12. Makau-Barasa LK, Greene SB, Othieno-Abinya NA, et al: Improving access to cancer testing and treatment in Kenya. J Glob Oncol 4:1-8, 2018.

13. Gichangi P, Estambale B, Bwayo J, et al: Knowledge and practice about cervical cancer and Pap smear testing among patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Gynecol Cancer 13:827-833, 2003.

14. Ngugi CW, Boga H, Muigai AW, et al: Factors affecting uptake of cervical cancer early detection measures among women in Thika, Kenya. Health Care Women Int 33:595-613, 2012.

15. Duron V, Bii J, Mutai R, et al: Esophageal cancer awareness in Bomet district, Kenya. Afr Health Sci 13:122-128, 2013.

16. Muthoni A, Miller AN: An exploration of rural and urban Kenyan women’s knowledge and attitudes regarding breast cancer and breast cancer early detection measures. Health Care Women Int 31:801-816, 2010.

17. Anderson BO, Shyyan R, Eniu A, et al: Breast cancer in limited-resource countries: An overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative 2005 guidelines. Breast J 12(suppl 1):S3-S15, 2006.

18. Universal Health 2030, Department of Research: Policy Brief on the Situational Analysis of Cancer in Kenya, February 2011. Available at http://publications.universalhealth2030.org. Accessed February 3, 2021.

19. Kazungu JS, Barasa EW: Examining levels, distribution and correlates of health insurance coverage in Kenya. Trop Med Int Health 22:1175-1185, 2017.

20 Ramrayka L: Improving cancer in Kenya: A pathway to hope. March 15, 2018. Available at www.roche.com. Accessed February 3, 2021.

21. Makau-Barasa LK, Greene S, Othieno-Abinya NA, et al: A review of Kenya’s cancer policies to improve access to cancer testing and treatment in the country. Health Res Policy Syst 18:2, 2020.

Dr. Jani is a Consultant Surgeon in the Department of Surgery at the University of Nairobi, the immediate Past-President of College of Surgeons of East, Central and Southern Africa and Chairman of OTPAK. Ms. Craig is Research Support Specialist at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. Dr. Are is the Jerald L & Carolynn J. Varner Professor of Surgical Oncology & Global Health; Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education; and Vice Chair of Education Department of Surgery, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Rooprai is a general surgeon in Westlands, Nairobi, and Consultant Surgeon, in the Department of Surgery at the University of Nairobi in Kenya.