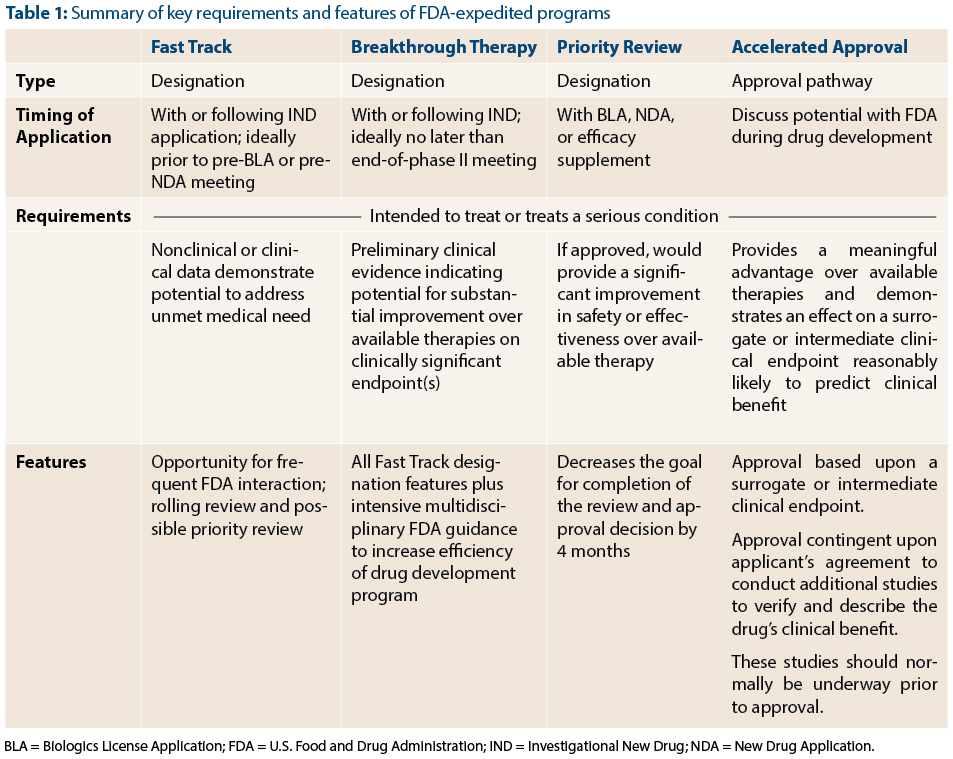

With the advent of Breakthrough Therapy designation, there are now four FDA programs to expedite the development of promising new agents: Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Priority Review, and Accelerated Approval (Table 1). These programs complement one another and serve a common goal: to speed the approval of effective treatments for serious conditions. Because the names of the programs convey the theme of speeding drug development and because there is some overlap between programs (such as Fast Track and Breakthrough Designation), they can be easily confused with one another. In this article, FDA reviewers Dr. Kluetz and Dr. Donoghue, address questions relating to the role of expedited programs for the development of cancer therapies.

New Expedited Programs Guidance

What has the agency done to help stakeholders better understand these expedited programs?

Dr. Kluetz: In June 2013, the FDA published a draft guidance, available online,1 describing the agency’s expedited programs for serious conditions. Multiple offices at the FDA, including OHOP, are currently in the process of revising the document based on public comment. In addition to clarifying Breakthrough Therapy designation and changes to Accelerated Approval, the guidance provides more detail on what is meant by regulatory terms such as “serious condition,” “available therapy,” and “unmet medical need.” The guidance is intended to be appropriate for all therapeutic areas developing drugs for serious conditions, not just oncology.

Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy Designations

What are the differences and similarities between Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy designations?

Dr. Donoghue: Both Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy designation are designed to speed up drug development, but the level of evidence required to qualify, and the degree of FDA interaction provided by these designations differ. The FDA may grant Fast Track designation at any time during development, including prior to initiation of the first-in-human trial in cases where the nonclinical data provide convincing evidence of the potential of the therapy to address an unmet medical need.

In contrast, Breakthrough Therapy designation requires preliminary clinical data showing a drug’s potential to provide a substantial improvement over available therapy. Breakthrough Therapy designation confers all the benefits of Fast Track designation in addition to intensive interaction and guidance from the FDA throughout the drug development process. Given the amount of resources that are expected to be allocated to a Breakthrough Therapy product’s development, Breakthrough Therapy designation requires a higher level of evidence compared to Fast Track designation.

Clinical Data Requirements

Can you be more specific about what degree of preliminary clinical data might be necessary to qualify for Breakthrough Therapy designation?

Dr. Donoghue: In essence, we endeavor to confer Breakthrough Therapy designation to investigational therapies that we think have the potential to be transformative. While we would love to give a specific threshold for the degree of clinical evidence that would support a Breakthrough Therapy designation, the reality is that there are many factors that we consider.

In addition to clinical activity, we consider the relationship between the therapy’s mechanism of action and tumor biology, toxicity profile, and the context for its proposed use, including disease incidence and available therapies. With respect to clinical activity, recent Breakthrough Therapy designations for cancer therapies have largely been based on data from early phase clinical trials of drugs with acceptable toxicity profiles documenting durable response rates that are markedly higher than those of approved or standard treatments.

Designated Indications

How specific does the intended indication need to be for a Breakthrough Therapy or Fast Track designation? Will the drug always carry the Fast Track and/or Breakthrough Therapy designation once they are granted?

Dr. Donoghue: Both designations apply to a specific use for which a therapy is being studied, so a therapy being developed for multiple indications may have Breakthrough Therapy or Fast Track designation for one or more potential indications, but not for others. Additionally, the FDA may rescind Breakthrough Therapy or Fast Track designation if data accumulated during later stages of drug development are not as promising as the data supporting the initial designation, or if the treatment landscape changes due to the approval of new therapies of superior or comparable efficacy compared to the therapy under development.

Processing Breakthrough Therapy Requests

Has your office received many Breakthrough Therapy requests?

Dr. Kluetz: As of November 8, 2013, OHOP has received approximately half of the 104 Breakthrough Therapy designation requests submitted to the FDA. Of those submitted to OHOP that have had decisions rendered, we have granted Breakthrough Therapy designation to approximately one-third of the requests.

Is there any way to make the process of requesting a Breakthrough Therapy designation more efficient?

Dr. Donoghue: Actually, the process is pretty efficient, as long as companies provide sufficient information to support the Breakthrough Therapy designation request in a format that is well organized. We recommend that sponsors contact us to arrange a brief teleconference prior to submitting a request for Breakthrough Therapy designation. This provides an opportunity for sponsors to get an early read from our office regarding a therapy’s potential for Breakthrough Therapy designation, and an understanding of the format and types of information required for a Breakthrough Therapy designation request. This can save both the sponsor and the FDA a great deal of time. Advice communicated during the teleconference is not binding and would not prejudice the submission of a request for Breakthrough Therapy designation.

Have any of the products granted Breakthrough Therapy designation gone on to FDA approval?

Dr. Kluetz: Yes. Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) for previously treated patients with mantle cell lymphoma and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) in combination with chlorambucil (Leukeran) for the treatment of patients with untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were the first two Breakthrough Therapy–designated products approved by the FDA. Given that Breakthrough Therapy designation is a new addition to the expedited programs, both of these products received the designation late in product development. Not surprisingly, products that receive Breakthrough Therapy designation early in development are likely to derive the most benefit from intensive interaction with FDA. Nonetheless, both of these products benefited from enhanced communications and an “all-hands-on-deck” expedited review.

Accelerated Approval and Priority Review

What is Priority Review and how does it expedite drug development?

Dr. Kluetz: Unlike the other three programs, Priority Review affects only one aspect of drug development: the goal date for FDA review and action on a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA). Priority Review designation shortens the FDA’s goal date by 4 months. In OHOP, we have a track record of completing reviews ahead of the Priority Review goal date. The bottom line is that when we receive an application for a drug providing an improvement over available therapy, we do everything we can to complete the review and get the therapy out to patients as quickly as possible.

What is the Accelerated Approval program?

Dr. Kluetz: Accelerated Approval is one of the two types of approval pathways (regular approval or accelerated approval) available in the United States. The key to the Accelerated Approval program is the ability to use a surrogate endpoint or intermediate clinical endpoint that is considered “reasonably likely” to predict clinical benefit. For instance, response rate may provide an earlier assessment of drug activity and allow for shorter and smaller clinical trials. If the investigational drug shows a meaningful benefit over available therapy using such an endpoint, Accelerated Approval may be granted. However, by allowing a surrogate endpoint to be used, we accept a degree of uncertainty that, for example, the improvement in response rate may not predict overall clinical benefit (improvement in survival, patient function or amelioration of disease-related symptoms). To counter this risk, we require the company to conduct at least one confirmatory clinical trial to verify that the earlier endpoint truly predicts a meaningful benefit for patients.

Role of Response Rate

Speaking of surrogate endpoints, why is response rate supportive of Accelerated Approval in some cases and regular approval in others?

Dr. Kluetz: Overall response rate, the percentage of all partial and complete responders, is only one factor to consider. Other important variables include the location of the tumor and the likelihood it is causing symptoms; how long on average the responses last; the magnitude of response rate compared to available therapies; and the degree of tumor shrinkage being demonstrated.

For instance, in the case of vismodegib (Erivedge) for recurrent locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma following surgery, the location of the lesions (disfiguring and often symptomatic skin lesions) coupled with the magnitude and duration of responses were felt to demonstrate substantial evidence that these responses were clinically meaningful. In this context, vismodegib was granted regular approval based on response rate. On the other hand, a drug demonstrating a 30% to 35% response rate (all partial responses) of moderate duration in a single-arm trial in a refractory population of unselected non–small cell lung cancer patients holds a greater uncertainty that this finding is going to predict clinical benefit in the long run. In this case, response rate could be considered reasonably likely to predict benefit and Accelerated Approval would be more appropriate.

Pitfalls of Expedited Programs

What can prevent timely approval of a promising new cancer therapy despite use of one or more of the FDA’s expedited programs?

Dr. Donoghue: Pitfalls can occur during the course of drug development and NDA or BLA review, particularly when development occurs on a compressed timeline. With the emergence of targeted therapies designed for use in a subset of patients with tumors that harbor a particular molecular characteristic, issues relating to the codevelopment of an in vitro diagnostic device with acceptable performance characteristics can arise. For this reason, we strongly recommend that sponsors of new targeted therapies that rely on a device for patient selection interact early in the development process with the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiologic Health.

In addition, there have been cases, particularly with biologics, where our ability to review and approve an effective drug has outpaced a sponsor’s ability to scale the manufacturing process appropriately to support marketing and distribution of a new drug.

Lack of appropriate planning for verification of clinical benefit can also delay the approval process of a therapeutic candidate for accelerated approval. Therefore, it is vital that sponsors work with the FDA prior to submission of the NDA or BLA to reach agreement on the design of confirmatory trials. In fact, we strongly recommend that such trials be underway on or before the time of approval.

Finally, problems related to poor data quality, lack of readiness for clinical and manufacturing inspections and slow or incomplete responses to our information requests can hamper timely review of an NDA or BLA. Expediting drug development taxes the resources of both the FDA and the sponsor. It is therefore imperative that sponsors dedicate the appropriate resources and work with the FDA in advance to ensure that the necessary infrastructure is in place to prevent delays due to these avoidable problems.

Are there risks to expediting drug development?

Dr. Kluetz: Expediting the development of promising agents through use of these programs often entails smaller trials, which pose both efficacy and safety risks. With regard to efficacy, the risk is that the effect size may be overestimated and not confirmed in subsequent trials. Concerning safety, the risk is that there may be an underestimation of toxicity rates or an inability to detect infrequent but severe toxicities.

We have already seen examples of these risks with the withdrawal of the metastatic breast cancer indication for bevacizumab (Avastin) due to an inability to confirm the initial efficacy results, and the suspension of marketing and sales of ponatinib (Iclusig) after reports of substantially higher rates of serious vascular events than were originally seen. Neither of these cases is considered a failure of expedited programs such as Accelerated Approval; rather, they represent the calculated risks we accept in order to bring promising new agents to patients with life-threatening malignancies.

If these risks are known, what is FDA doing to mitigate them?

Dr. Kluetz: As previously mentioned, postmarketing trials required as a condition of Accelerated Approval will provide data intended to verify the efficacy demonstrated by the initial surrogate endpoint. These trials should be completed as quickly as possible in order to identify drugs that fail to verify benefit. Additionally, the smaller trials frequently seen with expedited development will require that safety be rigorously examined in the postmarketing period.

Postmarketing safety data are not only captured in clinical trials as postmarketing requirements and/or commitments, but also through spontaneous reporting to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System once the product is on the market. We continue to work on effective strategies to analyze postmarketing safety data, which will be increasingly important as we consider accepting smaller amounts of safety data for initial approval of novel therapies with large magnitude efficacy results.

Closing Thoughts

Any final considerations you’d like to convey about these programs?

Dr. Donoghue: I hope that we have shed some light on the four programs that sponsors and the FDA have at their disposal to expedite drug development for serious conditions. I believe these programs have been effective in hematology and oncology drug development and will continue to be used to hasten the approval of effective products for the benefit of patients.

Dr. Kluetz: As someone interested in genitourinary malignancies, it has been very rewarding to be involved with the review and approval of two recent therapies altering the treatment landscape for patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Both of these products took advantage of various expedited programs. I look forward to continuing to work together with drug developers using expedited programs, in addition to other strategies, to bring novel cancer therapies to the patients who need them.

Disclosure: Dr. Kluetz and Dr. Donoghue reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Guidance for Industry on Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions—Drugs and Biologics. Posted June 2013. Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM358301.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2014.