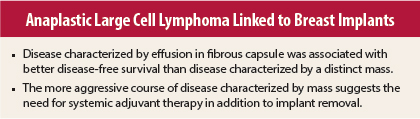

Only recently described, breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma usually presents as an effusion-associated fibrous capsule surrounding the implant and less frequently as a mass. Little is known about the natural history and long-term outcomes of such disease. In a study reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Roberto N. Miranda, MD, Associate Professor in the Department of Hematopathology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and colleagues assessed disease characteristics, treatment, and outcomes in 60 cases.1 They found that outcomes are better in women with effusion confined by the fibrous capsule, whereas disease presenting as a mass has a more aggressive clinical course.

Study Details

The investigators reviewed the literature for all published reports of implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma between 1997 and 2012. Corresponding authors for the published reports were contacted to obtain information on patient follow-up.

The 60 women had a median age of 52 years (range, 28–87 years). Median time from implantation to diagnosis (n = 59) was 9 years (range, 1–32 years). Location of the implant in 58 patients was the right breast in 37, the left in 20, and both in 1.

Implantation was for cosmetic purposes in 34 patients and for reconstructive surgery for breast cancer in 26; among 15 patients with known stage of breast cancer at time of implantation, 5 had stage I disease and 6 had carcinoma in situ. Type of implant in 51 patients was silicone in 23 and saline in 28. The surface of the implant was reported in only 21 patients; all were textured implants.

Presentation was characterized by effusion in 42 patients and by a distinct mass in 18, usually with associated effusion. Investigation for axillary lymphadenopathy in 29 patients was positive in 10, pathologic evaluation of lymph nodes in 8 patients showed lymphoma in 4, and 2 patients had positive nodes based on clinical or radiologic assessment. Among 59 patients with staging data at presentation, 49 (83%) had stage I, 6 (10%) had stage II, and 4 (7%) had stage IV disease.

In the 42 patients with tumor confined to the fibrous capsule, lymphoma cells were present as small clusters in the effusion or lining the capsule, without growth as a distinct mass. In 18 patients with mass presentation, a distinct mass of tumor cells within or beyond the capsule was found, with lymphoma cells in confluent sheets or loose clusters associated with a variable amount of necrosis or sclerosis. All tumors were strongly positive for CD30 and had a T-cell immunophenotype; all 57 tumors tested for ALK were negative.

Treatments

Capsulectomy and implant removal was performed in 56 (93%) of the 60 patients, with mastectomy also performed in 5 and axillary lymph node dissection in 5. Among patients for whom information was available, adjuvant chemotherapy was received by 39 (71%) of 55 patients and local radiation was received by 31 (55%) of 56, with 26 (47%) receiving both, and 13 receiving chemotherapy and no radiation.

Among the patients receiving no chemotherapy, 12 opted for watchful waiting after implant removal and 6 received radiation alone. Autologous stem cell transplantation was performed in 8 patients. Of 31 patients with identified chemotherapy regimens, all received CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) or CHOP-like regimens; of 28 who received a known number of cycles, 22 received 6.

Survival Outcomes

Follow-up ranged from 0.1 to 14 years (median, 2 years; mean, 3.1 years). Median overall survival was 12 years for all patients, including 12 years in those with mass and not reached in those without mass (P = .051). The 3-year and 5-year overall survival rates were both 97% in those without mass and 92% in those with mass, including 100% vs 82% (P = .0308) and 100% vs 75% (P = .0308) in those without vs with mass. Median progression-free survival was not reached in those without mass vs 1.8 years in those with mass (P = .005).

Among the 42 patients without mass, 39 (93%) had complete remission at last-follow-up; 6 (14%) had disease relapse, with 2 having persistent disease at last follow-up, 1 dying of unrelated causes at 7 years after relapse, and 3 having complete remission at last follow-up. Among the 18 with mass, 13 (72%) had complete remission at last follow-up; 9 (50%) had relapse, with 3 dying, 2 having persistent disease at last follow-up, and 4 having complete remission at last-follow-up.

There was no significant difference in overall survival (P = .44) or progression-free survival (P = .28) between patients receiving vs not receiving chemotherapy. Follow-up ranged from 0.1 to 10 years in the 16 patients not receiving chemotherapy (median, 1.5 years) and in the 12 undergoing watchful waiting (median, 1 year). There were no significant associations of survival with age, side of lymphoma, reason for implant, implant type, or time from implant to lymphoma.

The investigators concluded:

These data suggest that there are two patient subsets. Most patients who present with an effusion around the implant, without a tumor mass, achieve complete remission and excellent disease-free survival. A smaller subset of patients presents with a tumor mass associated with the fibrous capsule and are more likely to have clinically aggressive disease. We suggest that patients without a mass may benefit from a conservative therapeutic approach, perhaps removal of the implant with capsulectomy alone, whereas patients with a tumor mass may need removal of the implants and systemic therapy that still needs to be defined.

They noted that the median 2-year follow-up in this patent population is short and that it will prove valuable to continue follow-up of the cohort.

Disclosure: The study was supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute. For full disclosures of the study authors, visit jco.ascopubs.org.

Reference

1. Miranda RN, Aladily TN, Prince HM, et al: Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: Long-term follow-up of 60 patients. J Clin Oncol 32:114-120, 2013.