Targeted therapies have markedly improved outcomes in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, with median overall survival of greater than 2 years having been observed with sunitinib (Sutent) treatment. Objective responses, consisting mostly of partial responses, are observed in approximately 8% to 39% of patients receiving targeted agents. Complete remission appears to be rare, occurring, for example, in 3% of patients in the phase III trial of sunitinib as first-line treatment in metastatic renal cell carcinoma.1

Targeted therapies have markedly improved outcomes in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, with median overall survival of greater than 2 years having been observed with sunitinib (Sutent) treatment. Objective responses, consisting mostly of partial responses, are observed in approximately 8% to 39% of patients receiving targeted agents. Complete remission appears to be rare, occurring, for example, in 3% of patients in the phase III trial of sunitinib as first-line treatment in metastatic renal cell carcinoma.1

In a recent issue of Journal of Clinical Oncology, Albiges and colleagues report a retrospective analysis of complete remissions achieved in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors at 15 centers in the Groupe Française d’Immunothérapie.2 Patients included in the analysis had histologically confirmed metastatic renal cell carcinoma and had received sunitinib or sorafenib (Nexavar) monotherapy according to standard approved schedules. Sunitinib was given at 50 mg/d for 4 weeks with 2 weeks off. Sorafenib was given at 800 mg/d continuously in 4-week cycles. Patients must have achieved complete remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy alone or in combination with local treatment consisting of surgery, radiation therapy, or radiofrequency ablation.

The investigators identified 64 patients with complete remission (59 receiving sunitinib and 5 receiving sorafenib). The denominators for patient groups receiving sunitinib or sorafenib were not available for all centers; for the main center in the study, complete remission occurred in 6 patients (1.7%) of a total of 353 patients receiving either sunitinib or sorafenib. Most patients (94%) had clear cell histology, all had prior nephrectomy, and 56% had received no prior treatment. French classification prognostic grouping was favorable for 34% and intermediate for 61%. The number of metastatic sites prior to tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment was 1 in 41% of patients, 2 in 36%, and 3 or more in 23%.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Alone

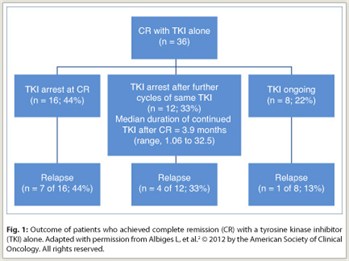

Of the 64 patients with complete remission, 36 (56%) achieved that remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment alone (Fig. 1). In these patients, the median time from start of tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment to complete remission was 12.6 months (range, 2–28 months). Of the 36 patients, 16 (44%) stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment at the time of complete remission, 12 (33%) continued treatment with the same agent for a median of 3.9 months after complete remission, and 8 (22%) were still on such therapy at the time of the analysis after a median of 10.3 months from the time of complete remission.

Of the 64 patients with complete remission, 36 (56%) achieved that remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment alone (Fig. 1). In these patients, the median time from start of tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment to complete remission was 12.6 months (range, 2–28 months). Of the 36 patients, 16 (44%) stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment at the time of complete remission, 12 (33%) continued treatment with the same agent for a median of 3.9 months after complete remission, and 8 (22%) were still on such therapy at the time of the analysis after a median of 10.3 months from the time of complete remission.

Relapse occurred in 7 (44%) of the 16 patients who stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment at the time of complete remission, 4 (33%) of the 12 who stopped treatment after additional cycles, and 1 (13%) of the 8 who were still receiving a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The median time from complete remission to relapse was 7.9 months (range, 3–32 months). Relapse occurred at a previously involved metastatic site in 5 of 12 patients with relapse. Thus, of the 28 patients who stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment, 17 (61%) remained in complete remission after a median follow-up of 8.5 months (range, 0.3–39.1 months).

Relapse occurred in 7 (44%) of the 16 patients who stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment at the time of complete remission, 4 (33%) of the 12 who stopped treatment after additional cycles, and 1 (13%) of the 8 who were still receiving a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The median time from complete remission to relapse was 7.9 months (range, 3–32 months). Relapse occurred at a previously involved metastatic site in 5 of 12 patients with relapse. Thus, of the 28 patients who stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment, 17 (61%) remained in complete remission after a median follow-up of 8.5 months (range, 0.3–39.1 months).

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Plus Local Treatment

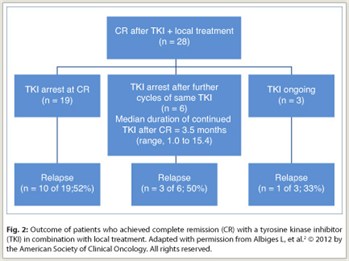

A total of 28 patients (44%) achieved complete remission with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor and local therapy (Fig. 2), consisting of surgery in 22 (79%), radiofrequency ablation in 2 (7%), and radiation therapy in 4 (14%). Most patients received local therapy for pulmonary metastases. The median time from starting tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment to complete remission was 18.5 months (range, 5–45 months), reflecting the fact that these patients needed local treatment after prolonged beneficial tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment to achieve complete remission. Residual viable tumor cells were present in each of 20 available samples from patients who underwent surgery. Of the 28 patients, 19 stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment at the time of complete remission, 6 continued to receive treatment cycles for a median of 3.5 months after complete remission, and 3 were still receiving a tyrosine kinase inhibitor at the time of analysis after a median of 8.2 months from the time of complete remission.

Relapse occurred in 10 (52%) of 19 patients stopping the tyrosine kinase inhibitor at the time of complete remission, 3 (50%) of 6 who received additional cycles before stopping, and 1 (33%) of 3 who continued to receive a tyrosine kinase inhibitor at the time of the analysis. Relapse occurred in a previously involved metastatic site in 9 of 14 patients with relapse. Thus, of the 25 patients who stopped tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment after complete remission, 12 (48%) remain in remission after a median follow-up of 10.7 months (range, 0.3–54.0 months).

No Predictive Factors for Relapse Identified

Complete remissions were achieved in patients with up to five metastatic sites, indicating that extent of disease is not prohibitive of complete remission. Most patients in the group had favorable or intermediate risk, although complete remissions were also seen in three poor-risk patients. The investigators could not identify any clinical or biologic factors that appeared to be predictive of complete remission.

No factors could be identified that distinguished patients who were more or less likely to relapse after discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Due to the small numbers of patients in each group, no conclusions could be drawn about differences in relapse rates between patients who continued therapy and those who stopped when complete remission was achieved.

The longer duration of treatment with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients achieving complete remission with local therapy underscores the potential benefits of maintaining such therapy as long as there is persisting clinical benefit. As noted by the authors, even if prolonging that therapy in patients with a good quality partial response does not result in conversion to complete remission, “[in] the case of stabilization of the lesion(s) and in the absence of new lesions, a local treatment may then be considered to achieve [complete remission].” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Albiges reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al: Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib versus interferon alfa in first-line treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27:3584-3590, 2009.

2. Albiges L, Oudard S, Negrier S, et al: Complete remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. January 9, 2012 (early release online.).