Richard L. Schilsky, MD, FACP, FSCT, FASCO

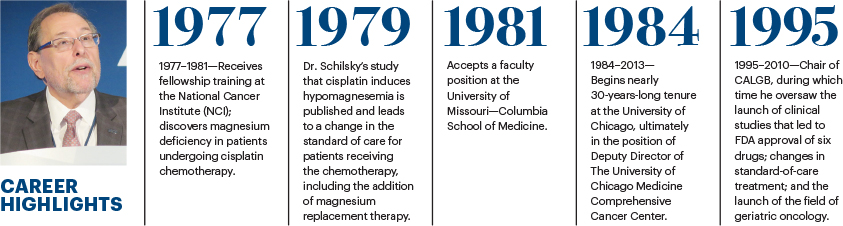

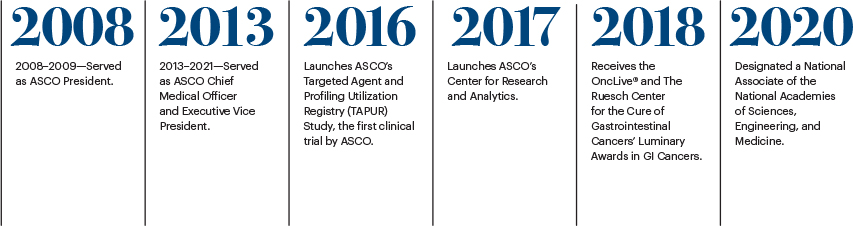

The medical career of Richard L. Schilsky, MD, FACP, FSCT, FASCO, spans more than 4 decades and includes a roster of nearly unprecedented accomplishments in patient care, research, and mentoring. He has held leadership positions in academia, first at the University of Chicago, where he spent the bulk of his career; as Chair of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB, now called the Alliance) from 1995–2010; President of ASCO from 2008–2009; and for the past 9 years, as Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President of ASCO. On February 15, 2021, Dr. Schilsky will retire from ASCO but expects to remain professionally engaged in the oncology community, albeit at a less hectic pace.

“I made the decision to retire from ASCO early last year because I was at a point in my life when I was ready to stop working full time. I only know one way to work, which is full-speed ahead, and I felt that after all these years, it was time to step back a bit from that pace of work,” said Dr. Schilsky. “But I expect to be fully professionally engaged in projects that interest me, although I don’t yet know exactly what they all will be.”

One project he has already committed to over the next year is continuation of his work on ASCO’s Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) Study (www.tapur.org), a basket trial he launched in 2016, the first clinical trial attempted by ASCO. The purpose of this phase II nonrandomized clinical trial is to identify potential signals of drug activity in patients with advanced cancer and a potentially actionable genomic alteration. The drugs included in the TAPUR Study are targeted therapies that have already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for other indications. Currently, more than 2,000 patients have been treated with a TAPUR Study drug at 123 sites across 24 states.

Since the launch of the TAPUR Study, Dr. Schilsky has steered the establishment of several other research innovations at ASCO, including its Center for Research and Analytics (CENTRA; www.asco.org/research-guidelines/center-research-analytics-centra), which aims to make a variety of ASCO data assets available to the oncology community and provide consultation and support for research and analysis. Most recently, Dr. Schilsky was instrumental in developing the ASCO Survey on COVID-19 in Oncology Registry (www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/blog-release/documents/Final-COVID19-Registry-Study-Schema-Revised-10-6-20.pdf), with the goal of capturing how the coronavirus affects patients with cancer and how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the delivery of high-quality cancer care. This past November, ASCO launched a COVID-19 Registry Data Dashboard (www.asco.org/asco-coronavirus-information/coronavirus-registry/covid-19-registry-data-dashboard), which summarizes the demographic and cancer information of the patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Since the dashboard was established, 45 practices nationwide have submitted data on 1,465 patients, and early analysis of the data is expected soon.

Dr. Schilsky also played a key role in the development of CancerLinQ®, ASCO’s big data initiative in oncology; ASCO’s Data Library (www.asco.org/research-guidelines/center-research-analytics-centra/asco-data-library), a repository of research information, including data from the TAPUR trials, which will be available later this year; and ASCO’s Value in Cancer Care Framework, which assesses the value of new cancer therapies based on clinical benefit and side effects in the context of financial cost.

Dr. Schilsky counts these accomplishments during his tenure as ASCO’s Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President among the proudest of his long, stellar career. “I’ve tried to position ASCO as a credible force in clinical cancer research that I hope will allow the Society to continue to generate valuable data from its unique position in the cancer community and unique resources over the years to come.”

Destined for a Career in Medicine

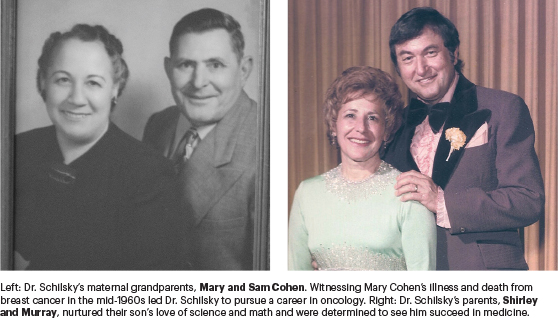

Dr. Schilsky’s career in oncology was foretold in an essay he wrote when he was in the 6th grade, in which he described his hope to enter the field of medical research, “searching for cures to diseases such as cancer and leukemia. In this way, I would be helping people more than if I would treat them for things like broken bones.” This desire was nurtured by his parents, Shirley and Murray, and fortified by the death of Dr. Schilsky’s maternal grandmother, Mary Cohen, from breast cancer some years later. The experience of witnessing the devastating effects the disease and treatment had on his grandmother left such an indelible impression on Dr. Schilsky that he has carried the memory throughout his career as a reminder to always put patients’ concerns first in any treatment decision. It’s a guiding principle, said Dr. Schilsky, that has influenced every career decision.

After earning a degree in medicine from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine in 1975, Dr. Schilsky completed his internal medicine residency at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas and then began fellowship training in medical oncology and clinical pharmacology at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1977. During that time, he made a decision to specialize in gastrointestinal cancers and inadvertently made a major contribution to the treatment of cancer, which changed the standard of care for patients prescribed the then experimental chemotherapy drug cisplatin.1

Remembrance of Things Past

Dr. Schilsky discovered that cisplatin produces magnesium deficiency, causing serum electrolyte imbalances and tremors in patients. Here he describes the circumstances of that discovery.

“When I was a fellow at the NCI, cisplatin was still an investigational drug. We had a phase II trial testing the drug in patients with ovarian cancer. One day, a patient in the study called me and said she was shaking all over, and I wondered if she was experiencing rigors, which would be a sign of infection. At the time, no one knew much about the side effects of cisplatin. I thought maybe her blood counts were low and maybe she had an infection, so I had her come into the clinic for an examination.

“What was happening is that she was actually twitching all over. As I examined her, it was obvious that she was displaying some of the classic symptoms of a low calcium level. I did bloodwork and the initial findings were that her calcium level was very low. We admitted her to the hospital and gave her hydration and calcium replacement; her symptoms started to improve, but they didn’t go away. Several hours later, we got back a result that her blood magnesium level was almost undetectable; as soon as we gave her magnesium replacement therapy, all of her symptoms resolved, and she was fine. But that raised the question of, what was the cause of this low magnesium level?

“A common thread to me in my career is building programs that bring people with unique skills together to tackle an important problem.”— Richard L. Schilsky, MD, FACP, FSCT, FASCO

Tweet this quote

“I didn’t know too much about magnesium homeostasis in those years. I had the good fortune of finding experts at the National Institutes of Health who could give me some information and insight into the problem. We theorized that because cisplatin caused damage to the kidneys, maybe it induced a state in which magnesium was leaking out of the blood through the kidneys and coming out in the urine.

“We confirmed that to be the case in this particular patient, but then we did a more formal research study with a larger number of patients who had received cisplatin therapy. We found that the vast majority of these patients within a short time of being given chemotherapy started leaking magnesium in their urine and needed to have magnesium replacement. That whole saga began, as it often does in medicine, with caring for a patient and making a careful clinical assessment of the patient’s complaint.

“Today, hypomagnesemia is a nonissue for patients taking cisplatin-containing therapy, and magnesium replacement therapy is part of routine care. Many years later, when I was an attending physician at the University of Chicago, I was making rounds on our inpatient oncology service with our residents and medical students. They presented a patient to me who had been admitted the night before with bladder cancer. The patient had been receiving cisplatin chemotherapy, and his electrolytes were all out of whack. His potassium and magnesium levels were low, and they were theorizing about the cause of these electrolyte abnormalities. They had good theories, which I challenged. I asked the residents and students if they considered the possibility that these low electrolyte levels, particularly in magnesium, could be related to the patient’s chemotherapy? They said ‘No, we’ve never heard of anything like that happening.’ Then a resident said, ‘We’ll think about what you said, but we’re going to get a renal consult.’

“The next morning, I went on rounds and asked how the patient was doing. The group said they had replaced all of the patient’s low electrolytes, and he was doing fine. I asked what the renal consultant said, and they very sheepishly took out the patient’s chart, which had a note from the renal consultant. Stapled to the note was a copy of my 1979 paper describing low magnesium levels from cisplatin. I thought, maybe now this new generation of doctors will think I have some credibility.”

Measuring Past Accomplishments

Following his fellowship at the NCI, Dr. Schilsky accepted an offer as Assistant Professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology, at the University of Missouri Columbia School of Medicine but soon returned to the University of Chicago, where he remained for nearly 30 years. There, Dr. Schilsky rose to top leadership positions, including Director of the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center, Associate Dean for Clinical Research, Chief of the Section of Hematology/Oncology in the Department of Medicine, and Deputy Director of the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center.

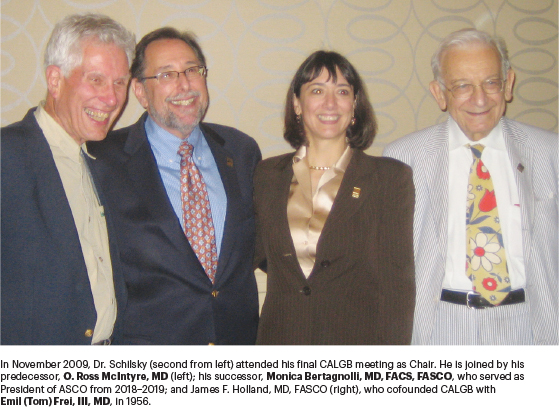

During his tenure at the University of Chicago, Dr. Schilsky took on another high-profile role as Chairman of CALGB. Over the next 15 years, he oversaw the launch of a series of clinical studies in such diverse cancers as multiple myeloma, breast cancer, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia, kidney cancer, and childhood T-cell leukemia or lymphoma. The findings from these trials resulted in FDA approval of six drugs in the treatment of those diseases; they included lenalidomide for myeloma maintenance therapy following transplant, paclitaxel for adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, 5-azacitidine for MDS, bevacizumab for kidney cancer, nelarabine for childhood T-cell leukemia or lymphoma, and midostaurin for FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia.

Bringing Together ‘the Best and the Brightest’ in Oncology

Here, Dr. Schilsky details the work of the CALGB group and the breakthroughs they made in cancer research.

“Chairing CALGB was probably among the most satisfying 15 years of my life, rivaled only by my years at ASCO. I loved chairing CALGB because I got to know the best and the brightest and the most dedicated people in oncology. These clinicians were all volunteers who were willing to give their time to come together to devise clinical trials that made a difference in cancer care. At the end of the day, although it’s nice to be published, if you want to make a difference in the lives of patients, you have to get new drugs approved by the FDA.

“I can’t take personal credit for the accomplishments we achieved, because it was a group effort. But our results are very gratifying. Some of our study results led to first-time FDA drug approvals, including 5-azacitidine for the treatment of MDS. Today, that drug is still the standard of care for the disease. The same is true for the FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin for acute myeloid leukemia.

“Equally gratifying about my time at CALGB are the studies we conducted that changed the standard of care in cancer treatment even though they didn’t result in a specific drug approval. Probably among the foremost successes were studies conceived by Larry Norton, MD [Senior Vice President, Office of the President; Medical Director of the Evelyn H. Lauder Breast Center; and Norma S. Sarofim Chair in Clinical Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center]. His studies demonstrated that giving dose-dense adjuvant chemotherapy to patients with breast cancer produced better outcomes and was less toxic than the standard adjuvant chemotherapy strategy,2 and that was another paradigm shift in oncology care.

“Another major accomplishment of the group in those years was the realization that there were few data on how to effectively treat older adults with cancer, even though most people diagnosed with cancer were older. At the time, they were not widely represented in clinical trials.

“We have not solved the problem of every type of cancer yet, but we continue to make progress much more quickly than ever before.”— Richard L. Schilsky, MD, FACP, FSCT, FASCO

Tweet this quote

In 1996, I launched the Cancer in the Elderly Committee. I asked oncologist Hyman B. Muss, MD [Mary Jones Hudson Distinguished Professor of Geriatric Oncology and Director of the Geriatric Oncology Program at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center] and geriatrician Harvey Jay Cohen, MD [Walter Kempner Distinguished Professor of Medicine, in the School of Medicine; Emeritus Director of the Center for the Study of Aging & Human Development; and Faculty Research Scholar of DuPRI’s Center for Population Health & Aging at Duke University School of Medicine] to co-chair the committee, which they did for the next 20 years. During that time, they established the entire field of geriatric oncology, which is now a well-established aspect of cancer care.

“Today, almost every leader in the field of geriatric oncology has been influenced by the work of that committee. So, that for me was another real career highlight.”

Contributing to ASCO’s Success

Another highpoint in Dr. Schilsky’s career came when he was elected President of ASCO in 2008; he gained firsthand exposure to the complex issues plaguing oncologists and a venue to help solve some of these problems. Five years later, Dr. Schilsky joined ASCO full time in a newly created position of Chief Medical Officer. He later took on the additional title of Executive Vice President of the Society, a leadership role he said he had been preparing for his entire career.

“I came to ASCO feeling like I had a really good grasp of all aspects of clinical cancer research, many facets of cancer care, and a variety of administrative structures, both on the national and institutional levels. These aspects are important to the success of the research enterprise, and this experience helped me enormously both to serve ASCO and also to carve out my own programs,” said Dr. Schilsky. “Fundamentally, what I’ve tried to do and what I think I’ve accomplished to a great extent is to enable ASCO to be an active participant in research and not just an organization that disseminates the research done by others. At this point, as I’m getting ready to depart from ASCO, I think the Society is in a very strong position to build on what we have developed.”

A Lasting Legacy

As Dr. Schilsky looks over his 40-year career in oncology, he admits he never imagined how gratifying his work would be.

“What stands out to me is all of the people I’ve had a chance to get to know and to work with and to mentor over these many years. When I think about what I’ve enjoyed most, a common thread to me in my career is building programs that bring people with unique skills together to tackle an important problem. That’s what I did as Director of the University of Chicago Cancer Research Center. When I took it over in 1991, I had a limited period to reorganize the center before submitting a competing renewal application for our Cancer Center Support Grant to the NCI.

“I completely reorganized our programmatic structure and restructured our core facilities. However, the key to accomplishing all that was getting to know the faculty across the entire institution who were working in some way in the field of oncology and bringing them together to address common research themes. The process of doing that helped the faculty foster collaborations they might not otherwise have made on their own. To see the cancer center get back on the right track and thrive was very satisfying to me.

“When I took over as Chair of CALGB, I had that same perspective, except now I had the opportunity to work on a national playing field and bring people together from across the 250-plus CALGB member institutions scattered across the United States and find the best and the brightest to work on the most innovative research questions of the day. The result is we were able to make substantial progress in a number of different areas.

“What has helped me to be successful at ASCO is the very broad experience in clinical care and research I gained over the years. There are very few people who have had the opportunity to serve as Director of a major cancer center, Chair of a large clinical trials cooperative group, and President of ASCO, in addition to serving on the NCI Board of Scientific Advisors for 12 years. These roles not only gave me a lot of insight into how the NCI worked, but the opportunity to influence the agency’s decision-making as well.

“What is most gratifying to me are the comments I continue to receive decades later from former trainees and young investigators I helped early in their careers, many of whom are now leaders in their own fields, about how much I influenced their careers and helped them to realize their full potential. Getting that kind of feedback is very satisfying and something I am very proud of.

“It is also extremely gratifying to see the immense progress we have made in cancer care for our patients. When you have the 40-year perspective I have, you can really appreciate the advances that have enabled us to cure cancer in a significant fraction of patients. We obviously have a lot of work to do in treating advanced cancers, but even here, we’ve made very substantial progress over the past 2 decades with the era of precision medicine in oncology.

“When I was a fellow at the NCI, there seemed to be no hope for many of the patients we treated, especially those patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma, for whom we had nothing to offer. Now, we have targeted therapies and immunotherapies enabling many patients to live long and productive lives with their cancers in durable remissions. We have not solved the problem of every type of cancer yet, but we continue to make progress much more quickly than ever before.”

Looking to the Future

Other than his commitments to remain active in the continued development of ASCO’s TAPUR Study and as an ASCO volunteer, for the first time in more than 40 years, Dr. Schilsky is not sure what his next professional endeavor will be. As in his past medical career, the deciding factor in his decision-making will be what he can bring to the new role that will make a difference in patients’ lives.

“I will continue to support ASCO in any way that I can be helpful, and then I’ll see what other opportunities come my way. For me, the key to accepting any new challenge will be the answers to these questions: Is this something I will enjoy doing, and is it something that will enable me to have an impact on improving patient care? If these two conditions are met, I’ll probably do it.”

DISCLOSURE: ASCO has received research grants from the following participants in the TAPUR Study: AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, Lilly, Merck, and Pfizer.

REFERENCES

1. Schilsky RL, Anderson T: Hypomagnesemia and renal magnesium wasting in patients receiving cisplatin. Ann Intern Med 90:929-931, 1979.

2. Fornier M, Norton L: Dose-sense adjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 7:64-69, 2005.