For this installment of The ASCO Post’s Living a Full Life series, Guest Editor Jame Abraham, MD, FACP, spoke with Laurie Glimcher, MD, President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI). She is also Director of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, Principal Investigator of Cancer Immunology and Virology at DFCI, and the Richard and Susan Smith Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Glimcher grew up in Brookline, Massachusetts. From a young age, she was fascinated by science. “I remember horrifying my two sisters by dissecting a frog when I was 6 years old. They’re both tax lawyers now,” said Dr. Glimcher. “Although I was deeply rooted in science, I also loved the humanities. When I was an undergrad at Harvard University, I co-majored in biology and literature. I think it stood me in good stead.”

Laurie Glimcher, MD

On her coexisting interests: “Although I was deeply rooted in science, I also loved the humanities, and I hope the emerging world doesn’t turn into only scientists and technologists, because humanism is so very, very important.”

On the challenges of a research career: “Although there’s a lot of excitement and inspiration in science, to make advances, you have to be willing to work through the frustrations and failures.”

Advice for young oncologists: “The most important thing is wanting to wake up in the morning and feel like you can’t wait to get to work because this is what you want to do. Some days you might feel that nothing is working, but you’ve got to have the discipline and the energy to go in and do it anyway.”

Parents as Mentors

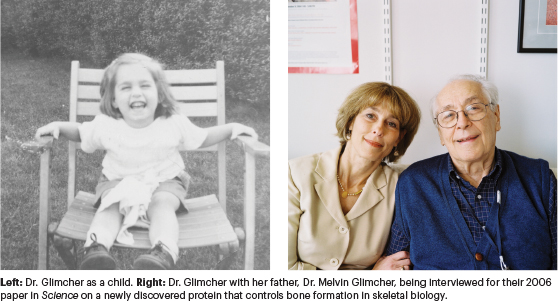

Asked about career influences, Dr. Glimcher replied: “Both of my parents had strong influences on my life and my career. My mother was a stay-at-home mother, and she always urged me and my two sisters to have independent careers—and there was never any question that we wouldn’t. She used to say that when I went to the pet store, I would come home with a one-eyed bird. I’ve always wanted to make things better for others, take care of people.”

She continued: “My father was a big personality. Like me, he was a physician-scientist. He served in World War II at the age of 17 and was upset that he didn’t get to go into combat; the military brass tested him and determined he was going to Duke to major in physics for 2 years and then to Purdue to learn how to be a mechanical engineer, because that’s what they needed. Thanks to the GI Bill, he attended Harvard Medical School and chose to be a biophysicist. He spent some time after he trained in orthopedic surgery to get the equivalent of a PhD by discovering how bones get calcified, which was a big deal. My father worked hard and was passionate about what he did. I think I inherited that from him.”

Research Career Emerges at Harvard

After graduating magna cum laude from Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Dr. Glimcher entered Harvard Medical School. At the end of the first year in medical school, she decided immunology would become a central part of her career path.

“Our immunology track was taught by Kurt Bloch, who was a rheumatologist and allergist at Mass General, and with his classes, I became completely fascinated by the idea that the immune system can recognize tissues as self and not as foreign—and that many diseases arise when that recognition becomes impaired,” said Dr. Glimcher. “So, I fell in love with immunology at that point and signed up for a one-on-one tutorial with one of the immunologists at Harvard, Emil Unanue. I did a reading course with Emil over the summer and also continued working in my dad’s laboratory on skeletal biology, but it was clear after that semester that immunology was the field I wanted to spend time in.”

GUEST EDITOR

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

She continued: “I spent the fourth year of Harvard Medical School in the lab of Harvey Cantor, and I remember running into my father during the middle of the day. He was Chair of Orthopedic Surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital at that time. He asked where I was going, and I told him home, because the experiments were so difficult, nothing was working, and I had just walked out of the lab in frustration. My dad said: ‘No, you’re not. That’s exactly when you have to go back to the lab and try twice as hard. That’s the essence of research.’ He was absolutely right, because although there’s a lot of excitement and inspiration in science, to make advances, you have to be willing to work through the frustrations and failures. You have to accept that 90% of your experiments aren’t going to work, your papers can get rejected, your grants can fail to get funded, and you still have to be passionate about what you’re doing.”

Dr. Glimcher added: “Harvey Cantor said something to me that I have never forgotten. The best way to understand autoimmune disease is to understand the normal immune system. I think that’s absolutely true.”

A Mentor’s Second Bit of Advice

Near the end of her work in Dr. Cantor’s research laboratory, Dr. Glimcher set her sights on postdoctoral training and sought advice from her valued mentor. “I asked Harvey where I should go, and he said I should probably should go to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) because it’s got the greatest collection of top-notch immunologists (other than Harvard), and it’s a wonderful environment. I think that was really true,” she commented.

“My husband was also interested in training in immunology, so I went to work with Bill Paul, and my husband went to work with David Sachs. Those were 3 wonderful years. I wasn’t on call every other night. I had our first child, my daughter, a couple of months after I got there and actually stayed out of work for a whole week, which is more than I did for our two sons who followed, where I literally got out of the hospital and went back to the lab the next day,” Dr. Glimcher noted.

“I had learned that you have to take big risks if you want to allow for the possibility of making major contributions. And I decided I was going to ask big questions and do high-risk experiments, and if they didn’t work—if my lab were to go up in flames—then I could always take care of patients,” she said.

“I had specialized in rheumatology because of autoimmune diseases, which I found fascinating, again, in that the immune system could recognize self from non-self. When it went awry, that led to either autoimmune disease, when you have too much activation of the immune system, or the other half of the coin, cancer, where your T cells are exhausted,” said Dr. Glimcher.

“It kind of reminds me of Israel,” she mused, “where I had family who ran kibbutzim. There’s this wonderful book by Dan Senor and Saul Singer, Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle. They describe Israel as a “start-up nation” because its history is analogous to founding a company—if it doesn’t work, you just go on and found another one and another one until it does work. So, back to the lab, even though 90% of your experiments won’t bear fruit, we were fortunate to have several that I hope were major contributions to the field of immunology.”

Fellowship at Mass General

After her tenure at the NIH, Dr. Glimcher returned to Massachusetts General Hospital for a fellowship in rheumatology. “When I moved back to Mass General to do my rheumatology fellowship, I was just so excited by the project that I wasn’t willing to give it up. Before I left, I submitted a grant proposal to the NIH, and then there I was with an R01. I had some funds and had a little lab—really teeny—and hired a technician. I combined full-time clinical work learning rheumatology with trying to keep the lab going,” said Dr. Glimcher.

What was her original motivation for learning rheumatology? “Frankly, I was fascinated by diseases such as scleroderma and lupus. They’re just completely unexplained diseases, unsolved in terms of their etiology. I think we understand their pathogenesis much better today, but what kicks them off is still not fully known. And from a practical point of view, it’s a small field with a small number of diseases, and most of it involves outpatient care. Of course, you have some terribly sick patients, but the arsenal of therapeutics has grown considerably,” she said.

After completing her fellowship, Dr. Glimcher made a career move to Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She also served at Harvard School of Public Health, where she ran a large, well-funded laboratory. She also directed the Division of Biological Sciences, and at Harvard Medical School, she headed one of the top immunology programs in the world. “I spent a lot of my time promoting and developing young women in science and medicine. I saw rheumatology patients half a day per week and focused on my laboratory, which was exciting. I had wonderful graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who have done very well. I trained about 100 of them,” she said.

Looking for a Bigger Platform

After a while, Dr. Glimcher began thinking about pursuing a second career that wasn’t focused just on her own lab, one that could really make a bigger impact on academic medical centers, which she strongly felt were under threat. “I wasn’t actively looking, but in 2012, I got a call from Weill Cornell asking me if I was interested in becoming the next Dean of Weill Cornell Medicine. At first, I was hesitant, as I had a great job, and after all, I was a fundamental scientist, not an administrator. But then my husband suggested I at least take a look at the offer. I did, and it actually sounded exciting, so I took the position,” said Dr. Glimcher.

“When I arrived, I wanted to make it clear that I admire physicians who are at the bedside at least as much as I value researchers, because I knew that some of the faculty, the clinicians, were not going to be happy with having a dean who was a scientist. I went around to the various department faculty meetings, and I believe that most of the reservations about me were resolved,” she said.

Dr. Abraham asked Dr. Glimcher to shed light on some of her accomplishments at Weill Cornell. “I filled the Belfer Building with fantastic scientists. We started out by recruiting Lew Cantley, who is a major figure in oncology. Some of the faculty said I’d never get Lew Cantley to leave Harvard for Weill Cornell. I replied that we certainly wouldn’t unless we tried. Lew came and really helped build our cancer program. Together, we recruited dozens of wonderful scientists who were oncologists or interested in cancer,” she said.

“We raised a lot for philanthropy and were able to grow our scientific community, which was my first priority. I also moved into medical education, which, honestly, I did not know much about, but we had to redo our curriculum, because it hadn’t been updated since 1996. We got a group of people together who worked hard to come up with a new medical curriculum, which I think has served the institution well in every respect. After that, we reorganized the physician’s organization, which had been doing well, but we all thought it could be even better. And that was my 4½ years at Weill Cornell in a nutshell. In all, it was a rewarding experience.”

Near the end of her fourth year at Weill Cornell, Dr. Glimcher received a call from Josh Bekenstein, Chairman of the Dana-Farber Board of Trustees, asking if she would consider returning to Boston to become CEO of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “My first thought was that Sandy Weill and Hank Greenberg are not going to be happy with me, because I had only been there for 4½ years. But I really wanted to go back to Boston, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute is just an incredible place. I felt a little guilty, but the turning point was when my two sons, who live in Newton, sent me flowers and a card that said: ‘Mom, we love you and we miss you, and we want you to come back.’ That was it; I was heading back to Boston,” said Dr. Glimcher.

Patient-First Ethos

Dr. Glimcher was named President and CEO of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 2016. She is also Director of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center and the Richard and Susan Smith Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. “When I was at Harvard for all those years, I collaborated a lot with the researchers at Dana-Farber and knew it was an amazing group of scientists at Dana-Farber. What I didn’t realize—because I really wasn’t interested in it at the time—was how incredible the care and culture of compassion are at Dana-Farber. Almost from day one, I started getting hundreds of e-mails and letters from patients (or, if the patient had not survived, patients’ family members) saying the experience at Dana-Farber clinically was beyond anything they had ever experienced at any other hospital. It’s incredible, because usually when a patient reaches out to a CEO, it’s to complain,” said Dr. Glimcher.

“We have an unusual structure at Dana-Farber in that it’s 50% researchers and 50% clinicians, and there’s no barrier between them,” she continued. “We conduct 1,100 clinical trials a year, and for 20% of our patients, that’s their best option. Everybody helps everybody else, which results in our positive outcomes. For instance, I had a woman confide in me that her doctor told her that her breast cancer was essentially cured, and she didn’t need to come back for more visits. She said that she had made so many friends at Dana-Farber that she wanted to come back every 6 months to see everyone again. I hear that over and over again. Dana-Farber is known for the incredible care it delivers, and it is a reputation that is well deserved,” said Dr. Glimcher. “In my mind—of course, I’m biased—I think we’re the best cancer hospital in the country.”

Dr. Abraham asked if she had any closing words of advice for young oncologists beginning their careers. Dr. Glimcher replied: “Know that you’re going to have failures, and if you’re not failing, sometimes that’s not good, because it means you’re not daring enough. The most important thing is wanting to wake up in the morning and feel like you can’t wait to get to work because this is what you want to do. Some days you might feel that nothing is working, but you’ve got to have the discipline and the energy to go in and do it anyway.”

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Glimcher has served on advisory boards for Abro Therapautics and Repare Therapeutics; has served on the board of directors for Analog Devices Corporation and GlaxoSmithKline; served as a consultant for JP Morgan Health Care; is founder of KiiK Therapeutics; and is former Director of BMS and Waters Corp. Dr. Glimcher holds equity in all of these companies.