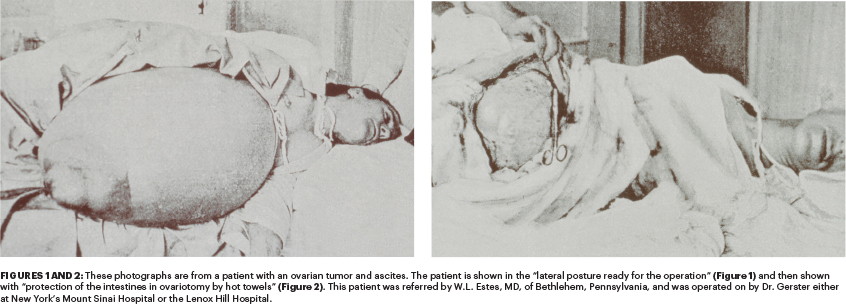

The text and photographs here are excerpted from a four-volume series of books titled Oncology: Tumors & Treatment, A Photographic History, The Antiseptic Era: 1876–1900 by Stanley B. Burns, MD, FACS, and Elizabeth A. Burns. The photographs appear courtesy of Dr. Burns and The Burns Archive. To view additional photos from this series of books, visit burnsarchive.com.

The first major American contribution to surgical practice was made in 1809 when Ephraim McDowell, MD, removed an ovarian cyst. Although he was not the first surgeon to perform this procedure (in 1701, Robert Houstoun, MD, punctured an ovarian cyst), Dr. McDowell’s success established this protocol as a viable medical therapy.

By the 1820s, other surgeons were attempting the operation. In 1825, John Lizars, MD (1794–1860), performed the first procedure in England; although it was unsuccessful, he published a monograph on the potential of the operation. Two other English surgeons further developed and refined the safety of the operation: Charles Clay, MD (1801–1893), and Sir Thomas Spencer Wells, MD (1818–1897). Dr. Clay, considered the pioneer of the procedure in England, coined the word “ovariotomy.” In 1842, he described his operation, which involved a “large incision from sternum to pubes.”

During his career, Dr. Clay performed 395 ovariotomies, with a mortality rate of 25%. He reported the statistical and practical analysis of his operations in 1864. Dr. Wells performed his first ovariotomy in 1857, and, by 1865, he had begun the publication of his two-volume Diseases of the Ovaries (1865–1872). Dr. Wells created a new type of forceps, which safely grasped the pedicle of the tumor, by reconfiguring a design by Jules Péan, MD. By 1872, he had performed 500 ovariotomies; by 1880, 1,000; and by 1890, 1,230.

In the United States, Washington Atlee, MD (1808–1878), was responsible for firmly establishing the use of this procedure by performing 387 ovariotomies. Prior to 1873, almost all of these 1,300+ operations took place without the benefit of antisepsis. By the 1880s, opening the peritoneum was safer due to the establishment of aseptic and antiseptic techniques, mortality rates had dropped to 4.4%, and the abdomen became the playground of the surgeons.

Method of Operative Preparation

New York surgeon Arpad Gerster, MD, described his method of operative preparation for abdominal intervention in his 1888 text, The Rules of Aseptic and Antiseptic Surgery. Surprisingly, most of the modern operative concerns, with the exception of the use of gowns, hats, masks, and gloves, appear to have been established; their use was introduced by 1910.

In minute detail, Dr. Gerster explained the preparation of the patient, as well as the surgeon’s hands, instruments, sutures, drains, and towels. He particularly noted:

[T]he presence of…stagnant bloody serum…will suffice to produce purulent peritonitis on the addition of a very small number of cocci…. The fluid (should)…be removed by artificial drainage…. Denudation of the surface layer of the peritoneal endothelium by caloric, or mechanical or chemical influences, is also conducive to the development of purulent peritonitis…. Practical conclusions to be drawn. Although the normal peritoneum will tolerate a greater quantity of infectious material than most surgical wounds…all precautions regarding cleansing…should be employed. Septic infection…is much easier to prevent than to cure. (He recommends the use of drains, use of no corrosive substances such as carbolic acid and careful toilet of the wound, and drainage.) If purulent peritonitis is undoubtedly established, reopening and irrigation of the peritoneal cavity with a hot 1:5,000 solution of corrosive sublimate may be taken into consideration, provided that the patient’s general condition should warrant such a procedure. (Dr. Gerster illustrated his special technique for ovariotomy.)

Excessive loss of body heat is a great factor in deterring collapse and should be guarded against most sedulously…. Hot, flat sponges or towels should hide from view everything except the very spot subject to surgical manipulation…. (Lister’s) Spray apparatus is harmless but unnecessary…and not used since 1881…. Control of hemorrhage is of the utmost importance…. Ample incision is the first condition for the safe removal of an abdominal tumor…. Close adhesions of the gut require special care. Recent adhesions are easily separated…. Old adhesions…may easily lead to injuries of the gut…. Blunt dissection by the tips of the fingers is proper…. Exploratory puncture and aspiration with a fine needle is very advisable…gentleness in handling the tumor…safe dissection (only) under the guidance of the eye…. The closure of the abdominal wound should be done as rapidly as thoroughness will permit, simplicity and solidity of the suture being the main desiderata. (Bladder emptying is described as a controversial issue, as a full bladder provides easy identification of the organ. Puncture of the tumor to remove fluid prior to the operation can cause peritonitis or adhesions, or at times cure the patient.) ■