There has been no better time than the present for women in the field of oncology: Women at all stages of their careers are finding more opportunities and avenues to excel. At the time of the last ASCO workforce survey, women made up 28.4% of the oncologist workforce, and that proportion is rising every year in each of the three main oncology subspecialties.1 In 2010, nearly 45% of oncology fellows were women.1

Yet, even with all of the hard-fought advances women in medicine have made over the past 40 years, challenges stemming from internalized biases at the personal and institutional levels persist. Despite equal-pay legislation, the wage gap between women and men continues.2 Women are often regarded as less competent than men, even when they possess equivalent experience and qualifications.3 Behavioral double standards abound, particularly in the workplace: Men who strive for leadership positions are praised as ambitious and direct, whereas women exhibiting the same behaviors are called bossy or rude.

In this article, early- and mid-career oncologists from institutions across the country—including clinicians, researchers, and former ASCO Presidents—share their insights on these challenges, as well as advice that has helped guide them through their careers.

‘Dysfunctional Pipeline’ and Glass Ceiling

Reshma Jagsi, MD, DPhil, of the University of Michigan Health System, has spent the past 10 years researching gender inequity in academic medicine. “In 1972, when Title IX was enacted, fewer than 10% of medical students were women,” said Dr. Jagsi. “When you look at the pipeline curve, you see a dramatic uptick over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, and by the time you get to the 1990s, about 40% [of medical school students] were women.”

Reshma Jagsi, MD, DPhil

After several decades of growth, why did the proportion of women medical students stall out before reaching 50%? A long-standing assumption has been that inequities in participation, pay, and opportunities for leadership can be explained by the social expectation of women to be the primary parent, sometimes called the “motherhood penalty.” According to Dr. Jagsi, however, parental status is not the primary factor for inequity in oncology. “Our research has shown that even women without children are not succeeding at the same rate or getting compensated equitably,” she said. Women in medicine face more than a motherhood penalty: They face a womanhood penalty.

“Some people make the argument that [medicine] is simply a slow pipeline—that careers in academic medicine are long, and the men who trained in the 1960s and 1970s are still around. [However,] when we look at cohorts like [the National Institutes of Health] K awardees and perform an actuarial analysis on the time from receipt of the K award to attainment of certain measures of success such as independent grants, similarly apt and motivated men and women are not succeeding at the same rate,” Dr. Jagsi said. “It’s not just a slow pipeline—it’s a dysfunctional pipeline.”

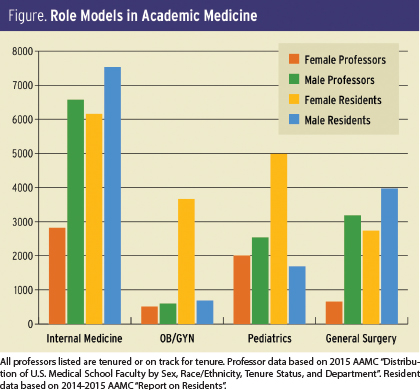

The systemic inequality extends to upper-level leadership in medicine, where women are severely underrepresented, a fact confirmed by data as well as anecdotally by many of the women who contributed to this article. “Though nearly half of all medical students are women, only 21% of full professors are women, and [only] 15% of department chairs and 16% of deans are women,” Dr. Jagsi said.

Sonali M. Smith, MD, of the University of Chicago School of Medicine and Lead of the ASCO Professional Development Committee’s Women in Oncology Work Group, identified this troubling trend in her own institution. “It’s very male-dominated at the top. There are very few section or department chairs who are women,” she said.

Sonali M. Smith, MD

Julie M. Vose, MD, MBA

Groups benefit when diverse viewpoints are represented. “Literature suggests that women are very good at leading teams and making all voices heard,” said Dr. Jagsi. “Women are the kind of leaders who encourage the participation of diverse individuals in a group. I think women are particularly well positioned to lead the field of oncology forward in this changing environment.”

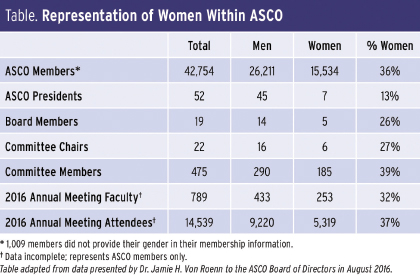

ASCO Immediate Past President Julie M. Vose, MD, MBA, is also optimistic about the future. “If you look at ASCO’s Leadership Development Program, for example, or look down the road at people going into oncology, participation is pretty much 50-50 [between men and women],” she explained. “As long as we have a good supply chain, so to speak, and the initiatives to mentor those people and provide opportunities, eventually—hopefully—things will even out, but it’s going to take time.”

Mentors Are Essential

Mentorship, as Dr. Vose noted, is a critical element for women to reach the career success they are clearly capable of achieving. From a research perspective, women are less likely to be coauthors on clinical trials, comprising only 16.3% to 26.4% of all first authors and 14.7% to 24.0% of all corresponding authors annually.4 A 2012 report from the National Cancer Institute found that women represented only 36.5% of K award applicants and 36.6% of recipients, even though women, earn 44.2% of U.S. medical degrees and 49.4% of U.S. biologic sciences doctorate degrees.5 The issue is not that women are unwilling to invest time and effort into research, but that institutional roadblocks can inhibit participation. Mentors can assist in overcoming those roadblocks.

At the beginning of her academic career in the early 1990s, Theresa Guise, MD, of Indiana University, experienced firsthand the kind of gender bias that was all too common a generation ago and persists even now.

Theresa Guise, MD

“I was submitting a VA grant,” said Dr. Guise, “and the head of research said something like, ‘Well, this is a pretty ambitious proposal’ and asked how old I was. I think I was 33 at the time, and he said, ‘You don’t really want to be so ambitious because you’ll probably be having children at the time you get this grant. Maybe you want to rethink that.’ I was just shocked that anyone would say anything like that, because I’m sure no one would say such a thing to a man in that situation.”

In the face of outright bias and stereotyping, mentors and allies helped Dr. Guise stay on track to achieve her research goals. “I went to my division chief, who was horrified, and he immediately took up the situation with the department of medicine chair, who had a discussion with the head of the VA research program,” she said. “After that, I submitted the grant—and it got funded.”

In many cases, it can be valuable for women to have multiple mentors to support different aspects of career advancement, from the professional to the interpersonal. Dr. Guise had two mentors who influenced different facets of her work. “I had formal mentorship with my research mentor, Dr. Gregory Mundy, who passed away a few years ago,” she said. “I also had informal mentorship from women faculty in my first faculty position at The University of Texas. Early in my career, Dr. Mary Samuels was a great mentor for practical aspects of research and making me aware of any specific gender issues. She was really helpful with my initial quest for public speaking and giving research seminars.”

Staring Down the Motherhood Penalty

Both the subconscious and overt discrimination a woman faces in the workplace is often exacerbated if she chooses to have children, seen in the form of greater wage gaps and fewer promotions.6 The expectation remains that when a woman has a child, she will act as the primary caregiver, even as stay-at-home fathers and paternity leave become more prevalent. According to a 2013 European Society for Medical Oncology study of women oncologists, 58.7% of participants believed that the work-family balance was the greatest challenge to progressing in their careers.7

Sandra M. Swain, MD, FACP

Dr. Smith, who has four children, struggled to find this balance when applying for research funding after her residency. “I didn’t get a career development award; I didn’t get any grants early on. I missed all the early opportunities for advancement because I was on maternity leave back to back to back,” she said. “I feel like my career didn’t start until I was maybe 7 years into a faculty position.”

Dr. Smith found her own definition of professional and personal success by thinking long term. “In the short term, it was really hard, but 15 years later, I’m happy where I am. We’re lucky in medicine that we can define success in many different ways, and so I just chose to define success as not including a career development award. That’s the best way for me to think about it,” she said.

ASCO Past President Sandra M. Swain, MD, FACP, of Georgetown University, also emphasized that you don’t necessarily have to reach every goal right away. “You can accomplish everything you want, but you don’t have to do it all at the same time,” she said. “People are living a lot longer, so you can take your career in steps to achieve the balance you need. I think it puts impossible stress [on you] if you feel that you need to do everything at once and do it all well, so taking some pressure off is important.”

Miriam A. Knoll, MD

In addition to the practical consequences of the motherhood penalty, working mothers also pay an emotional toll, often worrying that they are not doing enough for their families or their careers. Miriam A. Knoll, MD, of Hackensack University Medical Center, encouraged mothers to think about the positive impact their family experiences have on their professional lives.

“Well-rounded individuals who have interests outside of medicine such as their families experience less burnout and may have more empathy for their patients,” she said. “Certainly, a physician doesn’t need to have children to be a good oncologist, but you’re not a worse oncologist for having other interests outside of oncology that make you a well-rounded person.”

Anita Aggarwal, PhD, DO

Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH

Women can also consider how their work experiences may have positive effects on their family life. When her daughter was young, said Anita Aggarwal, PhD, DO, of the Washington DC VA Medical Center, “There were instances when I struggled because my child was at home and I was at work taking care of patients at the hospital during late nights. But this made me very patient, humble, and empathetic. I brought that home, and now, 20 years later, my daughter has grown up to be a very mature and confident physician herself. I must have done something right.”

Workplace flexibility is a necessity for mothers who remain strongly committed to their professions and are eager to contribute to their fields. The flexibility that Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH, of The University of Alabama at Birmingham, experienced when returning from maternity leave—and the understanding of a compassionate mentor—has shaped how she now trains her female residents.

“When my maternity leave was coming to a close, I felt I couldn’t leave a 3-month-old baby in a daycare situation while I went back to work, since we don’t have any family in the area. So I went to my mentor, who continues to be my mentor even now. He asked, ‘How much time do you think you need?’ I told him that if I could have 2 extra months, I would be much better prepared in terms of coming back to work. He did not blink once. He told me I could work from home for the 2 months, he paid me my full salary, and I stayed at home and I worked.” That flexibility paid off when, at the end of the 2 months, “We got our first New England Journal of Medicine paper out,” she said.

Having seen firsthand how flexible policies can make a big difference in new mothers’ ability to return to work and perform at a high level, Dr. Bhatia strives to create a similar environment for her own trainees.

ASCO Resources Support Career Advancement for Women

ASCO’s commitment to supporting its members at all stages of their careers includes helping women in oncology confront systemic inequality in the field and achieving their personal definition of professional success.

At the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting, ASCO opened the Women’s Networking Center, a place for women to openly discuss practical issues while also providing an opportunity for one-on-one mentorship. The Women’s Networking Center proved popular and was offered again at the 2016 Annual Meeting, with plans to continue and expand at future meetings.

The 2016 Annual Meeting also included a panel on “Women in Oncology: A Roundtable Discussion on Professional Development,” featuring Dr. Vose, Dr. Smith, and several other distinguished women in the field. The full session is available through ASCO’s Virtual Meeting.

The Society’s efforts to support the careers of female oncologists also include ASCO’s Women in Oncology Working Group. The group is currently involved in developing online resources and networking opportunities, including safe spaces where women can have robust and candid discussions about challenges and celebrate one another’s successes.

ASCO also offers the Women Who Conquer Cancer program, which was created to fund the promising careers of adept women researchers through the Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO’s Young Investigator Award. The program has seen enormous success since its launch in 2014: It has funded three such Young Investigator Awards and has raised a significant portion of the funds required to support an endowed Young Investigator Award.

Dr. Swain, the Founder and Chair of Women Who Conquer Cancer, said, “As a young investigator, I was one of [a] few women in academics, and now we see that not as many women stay in academics. It’s important to give them the tools for that career early on, because when someone gives a young investigator an award, it starts them on their way and gives them [the] confidence to continue.”

In 2016, Women Who Conquer Cancer established the Women Who Conquer Cancer Mentorship Award, which, according to Dr. Swain, “Recognizes not only an accomplished leader, but also a successful teacher, mentor, and role model who is actively nurturing some of the best and brightest minds in oncology.” When the nomination period opened, the Mentorship Award received a deluge of applications—a testament to the incredible work and excellent teaching currently being carried out by women in oncology.

Input from members is crucial for the continued improvement of the resources provided at ASCO meetings, as well as for programs ASCO hopes to offer women in the future. ASCO’s Professional Development staff have created a survey to track your feedback, all of which is carefully considered. Find the survey at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/WomenInOncology. ■

References

Originally printed in ASCO Connection. © American Society of Clinical Oncology. “Women in Oncology: Breaking Down Barriers and Looking to the Future.” ASCO Connection, November 2016:14-19. All rights reserved.