Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection generally can be treated the same as lymphoma in non–HIV-infected patients, with a few caveats, according to Lawrence D. Kaplan, MD, of the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

In particular, clinicians need to understand how best to integrate chemotherapy with antiretroviral therapy, he said during a presentation at the 2015 Annual Congress of Hematologic Malignancies, sponsored by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).1

Aggressive CD20-Positive B-cell Tumors

HIV-associated lymphomas, which are seen across a range of CD4 counts, are aggressive CD20-positive B-cell tumors. They are diffuse large B-cell tumors in two-thirds of patients, Burkitt lymphomas in one-quarter of patients, and other lymphoproliferative diseases in the remainder. Although among non–HIV-infected persons the incidence of these lymphomas is 10 to 20 per 100,000 person-years, the incidence among HIV-infected persons skyrockets to 170 per 100,000 person-years.

“That’s about the same incidence as breast or prostate cancer in the general population,” he noted. “In the HIV-infected group, this is a particularly problematic disease.”

Before the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy, standard chemotherapy rendered a 2-year overall survival rate of 10% to 20% in this population. Today, with combination antiretroviral therapy and more effective chemotherapy, 2-year survival reaches 70%.

“You can see from a variety of phase II trials in the antiretroviral era that overall survival now approaches that of the general population of patients,” noted Dr. Kaplan.

R-EPOCH Advocated for Most

Treatment for HIV-infected patients involves the use of rituximab (Rituxan) upfront, infusional chemotherapy, and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant for relapsed/refractory disease and the integration of antiretroviral therapy with antineoplastics.

Rituximab has been a game changer in lymphoma, but infectious deaths are a concern, primarily among patients with CD4 cell counts < 50/mm2, who are severely immunocompromised. “This is clearly a subgroup of patients with HIV and lymphoma who need special attention and for whom you must be careful about giving rituximab,” cautioned Dr. Kaplan. “For the rest of the patient population, the use of rituximab upfront is clearly indicated.”

As for which regimen to give with rituximab, R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) “is not a wrong choice,” he suggested, but R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin) should be the standard of care.

“Our experience suggests that this is a very well tolerated and perhaps more effective regimen in this patient population,” Dr. Kaplan said.

“This is not standard dose-adjusted EPOCH,” he explained. “What’s different is that the infusional agents—etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin—are never dose-escalated; that’s only the cyclophosphamide. The starting dose is based on a blood CD4 count, and the maximum dose is 750 mg/m2, which is the starting dose in standard dose–adjusted EPOCH. This is a little different regimen.”

Short-Course EPOCH-RR

Dr. Kaplan also described the short-course EPOCH-RR regimen, in which patients receive double doses of rituximab with EPOCH for two treatment cycles and then are assessed with PET-CT. Patients who are PET-negative receive one additional chemotherapy cycle, whereas PET-positive patients receive up to six cycles of EPOCH-RR. In a 33-patient study of this regimen, 5-year progression-free survival was 84%, and overall survival was 68%.2

“At UCSF, we have not yet incorporated short-course EPOCH, but we do routinely use standard dose–escalation EPOCH for patients who are not on clinical trials, and we find those patients tolerate therapy well,” Dr. Kaplan said.

A pooled multivariate analysis of 19 trials of more than 1,500 patients documented the superiority of EPOCH over CHOP and R-EPOCH over R-CHOP.3 Use of rituximab was associated with a 50% reduction in both disease progression and death.

The study also showed a lack of overall survival benefit in patients with CD4 cell counts < 50/mm2 (higher treatment-related mortality); and improvement in outcomes with concurrent use of combination antiretroviral therapy; and in patients with Burkitt lymphoma, a greater benefit with more-intensive regimens compared with infusional regimens.

Other Considerations

Focusing on the Burkitt lymphoma subset, Dr. Kaplan advised caution when using R-EPOCH (due to its intensity), until more data are in. At UCSF, he added, the standard of care for these patients is modified CODOX-M/IVAC (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine).

A recent study of 34 patients by Noy et al evaluated CODOX-M/IVAC in a regimen that added rituximab, reduced and/or rescheduled cyclophosphamide and methotrexate, capped vincristine, and used combination intrathecal chemotherapy.4 Overall survival was 72% at 1 year and 69% at 2 years, and modification of the regimen resulted in less toxicity.

Turning to the role of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant in relapsed/refractory patients, he noted that transplant is associated with overall survival that is as good as that observed in non–HIV-infected patients, and treatment-related mortality is not increased. The most common infectious complications in these patients are bacteremia and Clostridium difficile. Since cytomegalovirus reaction can be seen, he advised screening for it after transplant.

Integrating Antiretroviral Therapy

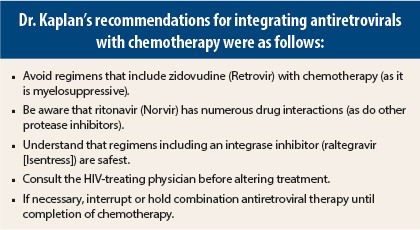

“The potential benefit to continuing antiretroviral therapy is better control of HIV replication and more rapid recovery of immune function post chemotherapy. The risk is more drug interactions with chemotherapeutic agents, antibiotics, antifungals, and so forth,” according to Dr. Kaplan.

The experience with conventionally dosed chemotherapy has been favorable, even when used alongside antiretroviral regimens containing protease inhibitors. Protease inhibitors, which inhibit CYP3A4 and are both substrates and inhibitors of P glycoprotein, however, do pose a risk for drug interactions and can potentiate chemotherapy-induced neutropenia.

“Avoid zidovudine at all costs. It will worsen myelosuppression. I don’t say that for many other antiretrovirals,” Dr. Kaplan elaborated.

“Be aware that protease inhibitor–based regimens are associated with drug interactions, but you can usually get patients through this while continuing their antiretrovirals. Integrase inhibitor–based regimens are associated with far fewer drug interactions, are well tolerated, and can be continued even during high-dose chemotherapy and transplant,” he continued.

“But if necessary—for example, for the patient with intractable nausea and vomiting—you can hold these antiretroviral regimens until you complete chemotherapy and resume when done,” Dr. Kaplan added. “This is better than starting and stopping antivirals multiple times, which can result in resistance.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Kaplan reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kaplan LD: Management of HIV-associated Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. 2015 NCCN Annual Congress: Hematologic MalignanciesTM. October 16, 2015.

2. Dunleavy K, Little RF, Pittaluga S, et al: The role of tumor histogenesis, FDG-PET, and short-course EPOCH with dose-dense rituximab (SC-EPOCH-RR) in HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 115:3017-3024, 2010.

3. Barta SK, Xue X, Wang D, et al: Treatment factors affecting outcomes in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas: A pooled analysis of 1546 patients. Blood 122:3251-3262, 2013.

4. Noy A, Lee JY, Cesarman E, et al: AMC 048: Modified CODOX-M/IVAC-rituximab is safe and effective for HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Blood 126:160-166, 2015.