A new and inexpensive serologic assay may help to predict recurrences of Merkel cell carcinoma, according to Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD, the Michael Piepkorn Endowed Chair in Dermatology Research at the University of Washington, Seattle, who helped develop the test.1 Dr. Nghiem and other experts in Merkel cell carcinoma spoke at the 3rd Annual World Cutaneous Malignancies Congress in San Francisco.

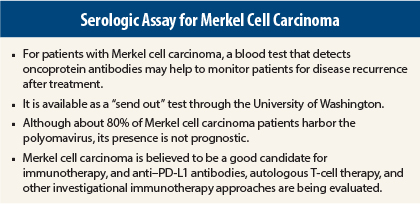

The Merkel cell polyomavirus is found in approximately 80% of Merkel cell carcinoma tumors. Although the prognostic impact of this virus in newly diagnosed patients has not been established, it can play a role in monitoring for tumor recurrence and thus in facilitating prompt treatment of progressive disease.

The assay is available as a “send out” test through the University of Washington, and costs approximately $200 (plus local laboratory fees). “This is much less expensive than radiological scans,” Dr. Nghiem pointed out.

Serologic Detection of Cancer Recurrence

Up to 50% of newly diagnosed Merkel cell carcinoma patients have oncoprotein antibodies that recognize the small T antigen; small T antigens help stimulate cancer cell proliferation and are virtually never present in healthy individuals. The test detects these antibodies (and antibodies to the capsid protein of the virus, which merely indicates viral exposure). Antibody titers are stable or reduced in Merkel cell carcinoma patients after treatment, but they increase by 20% or more in patients whose disease progresses, serving as an early warning sign of tumor recurrence, he said.

Dr. Nghiem explained the fairly simple way in which the assay signals a tumor recurrence: the small T-antigen titers are high at diagnosis, drop dramatically with treatment, and rise again if the cancer returns. The test has a specificity of 98% and a sensitivity of 78%.

Dr. Nghiem’s data (unpublished) indicate that, after the second blood draw, recurrence-free survival is approximately 90% at 2 years for patients whose titers continue to fall, 80% for those with stable titers, and 40% for those with increasing titers (P = .0003).

Only 50% of newly diagnosed Merkel cell carcinoma patients produce oncoprotein antibodies. A negative test at diagnosis means that the patient does not make the antibodies, and therefore the serology test will not be a useful monitoring tool. A positive test for oncoprotein antibodies (titer > 150) at diagnosis suggests the test could be useful in tracking the disease.

Changes in antibody titers are more important than the specific titer value itself, as individual patients’ titers vary. Titers typically will fall by about 10-fold in the first year, according to information on the University of Washington Reference Laboratory website.

Dr. Nghiem recommended that clinicians check the serology results within 3 months of a Merkel cell carcinoma diagnosis to determine whether the patient is an “antibody producer.” If so, that patient can be monitored every few months via the assay. Without a tumor recurrence, and depending on the stage of the disease and other risk factors, after 3 to 5 years, the test could be discontinued or used less often.

The guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) were recently updated to reflect trends in the care of patients with early-stage disease. The NCCN referenced the growing interest in the Merkel cell polyomavirus and the availability of this test, noting, “The value of baseline Merkel cell polyomavirus serology for prognostic significance and to track disease recurrence is being evaluated,” but made no recommendations at this point, said Christopher K. Bichakjian, MD, Associate Professor and Director of the Multidisciplinary Merkel Cell Carcinoma Program at the University of Michigan, who chairs the NCCN Committee on Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers.

“This is a development that may prove to be a prognostic tool and to supplement or replace routine imaging in the future,” Dr. Bichakjian commented.

Obtaining the Test

Oncologists should refer patients to their local laboratory for blood draws to initiate the process. The local laboratory “send out test coordinator” should contact the University of Washington Reference Laboratory Services Call Center (at 206-685-6066), which will set up an account for the ordering physician/clinic; collect the required billing and reporting information; and provide requirements for sample collection, processing, and shipping from the local laboratory.

More on the Role of the Merkel Cell Polyomavirus

Isaac Brownell, MD, PhD, Head of the Cutaneous Development and Carcinogenesis Section at the National Cancer Institute, addressed the interest in the polyomavirus as a possible etiologic factor in Merkel cell carcinoma, noting that the association is far from straightforward. Although 80% of Merkel cell carcinoma tumors harbor the Merkel cell polyomavirus, its presence does not equate with having the tumor; most Merkel cell polyomavirus infections are subclinical and not oncogenic, he said.

“We thought we had this nailed down, that Merkel cell polyomavirus infection equals Merkel cell carcinoma, but it’s not that simple,” he said.

Furthermore, Merkel cell polyomavirus status has no clear prognostic impact, as study results have been conflicting. Therefore, testing for the presence of the Merkel cell polyomavirus is currently irrelevant in patient care, except as a means of disease monitoring with the serology assay.

Immunotherapy in Merkel Cell Carcinoma

The determination of the Merkel cell polyomavirus status may someday become relevant in terms of treatment, however, as patients with circulating T cells that are Merkel cell polyomavirus–reactive can be enrolled in trials of autologous T-cell therapy, he said.

Shailender Bhatia, MD, of the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, described the emerging interest in this and other immunotherapeutic approaches in Merkel cell carcinoma. For autologous T-cell therapy, in patients with virus-positive tumors and virus-reactive circulating T cells, Fred Hutchinson researchers collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells from these patients, select the Merkel cell polyomavirus–reactive T cells, and expand the CD8-positive T cells. These cells are then reintroduced, along with cytokines to “rev up” the T cells to attack the tumor. In future studies, they will add immune checkpoint blockade, Dr. Bhatia said.

Based on the assumption that Merkel cell carcinoma is a cancer amenable to immune manipulation, trials of antibody-mediated blockade of the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) protein should open soon, and trials of its ligand (PD-L1) are already enrolling patients.

Researchers in Seattle and elsewhere are also evaluating local injections of immunotherapies, including interleukin-12 plasmid with in vivo electroporation and the Toll-like receptor (TLR4) agonist glucopyranosyl lipid. Other research efforts are evaluating the checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab (Yervoy) after excision, the addition of the F16–IL-2 antibody-cytokine fusion protein to paclitaxel, the efficacy of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors pazopanib (Votrient) and cabozantinib (Cometriq), and the targeting of the somatostatin receptor with various analogs (as Merkel cell carcinoma is a neuroendocrine tumor). ■

Disclosure: Drs. Nghiem, Bichakjian, Brownell, and Bhatia reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Nghiem P: A new serologic assay for early detection of recurrent Merkel cell carcinoma. 2014 Annual World Cutaneous Malignancies Congress. Presented October 31, 2014.