Our goal with this review of the pivotal years of oncology in Europe is to acknowledge the tremendous contributions of the early leaders in the field and to help young investigators learn from the past to better cope with the inevitable challenges of today and tomorrow.

“On ne connaît pas complètement une science tant qu’on n’en sait pas l’histoire.”(“It is impossible to be familiar with a science without knowing its history.”)

—Auguste Comte

This quote from French philosopher Auguste Comte reflects the wisdom of the ancient Greek historian and general Thucydides. In his notable work, History of the Peloponnesian War, which recounts the war between Sparta and Athens from 431 to 404 BC, Thucydides claimed that knowledge of the past is paramount to interpreting the future.

It is in this spirit that we have endeavored to outline the recent history of medical oncology in Europe, concentrating on 30 years of progress from 1955 to 1985. In part 1 of this exploration, we focus on initial attempts at systemic cancer treatment and the effort to develop cooperative research groups and clinical trials throughout Europe. In part 2 of this work, we detail the evolution of medical oncology in individual European countries.

Silvio Monfardini, MD

Lodovico Balducci, MD

Our goal in chronicling this extensive history is to help young investigators learn from the past, to better cope with the challenges they may face today and in the future. It is our hope that this review will inspire young oncologists to bring the same level of optimism and determination to their work that these European pioneers in medical oncology brought to theirs.

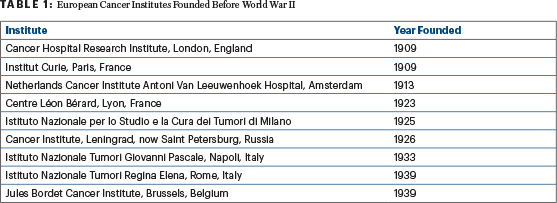

Evolution of Oncology Disciplines

European medical centers devoted to research on and treatment of cancer have been around since as early as 1909, when the Institute of Cancer Research was established as a research department of the Royal Marsden Hospital in London (Table 1). Prior to World War II, in North America, surgical and radiation oncologists were responsible for the management of solid tumors, including palliative care, whereas the management of leukemia and myeloma was entrusted to hematologists and consisted mainly of supportive care, such as pain control and blood transfusions.

Although the surgical treatment of cancer dates back to ancient times, the principle of surgically induced antihormonal therapy emerged in 1896, when British physician Sir George Thomas Beatson, MD, demonstrated that surgically induced menopause caused the regression of metastatic breast cancer.1 In 1941, Canadian-born Charles B. Huggins, MD, demonstrated that most cases of metastatic prostate cancer were responsive to androgen deprivation through bilateral orchiectomy, and in 1966, Dr. Huggins received a Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology for his research on the relationship between hormones and prostate cancer.2 Years later, the development of hormone therapy for these cancers would supplant the need for surgical ablation of estrogens and androgens in breast and prostate cancers.

The initial role of internists in cancer care was mainly confined to the

management of systemic manifestations of advanced cancer, which included fever, pain, anemia, infection, hypercalcemia, and hyperuricemia. By ameliorating these complications, internists were able to improve the quality of life of patients and provide additional weeks of meaningful survival.

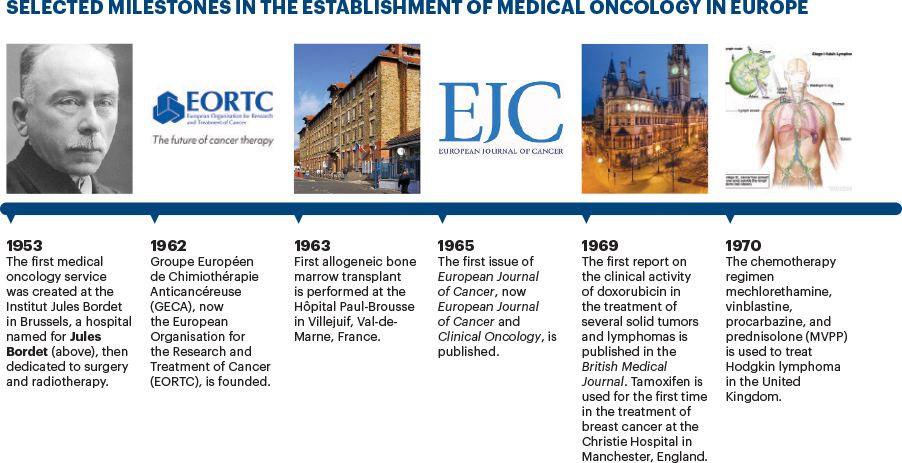

It wasn’t until 1953 that an independent medical service was created by Henry Tagnon, MD, with the goal of establishing a comprehensive cancer center at the Institut Jules Bordet in Brussels, which had previously been dedicated to surgery and radiotherapy. In addition to managing the systemic manifestations of cancer, the role of this new service was to administer the first few antineoplastic agents available, including antimetabolites and alkylating agents, which were most often given according to an empiric schedule on a daily basis until the development of toxicity.

Over the next decade, a number of antineoplastic drugs were developed for the treatment of cancer, and by 1968, American physician Byrl James “B.J.” Kennedy, MD, advocated for the creation of a medical oncology specialty devoted to systemic hormonal and cytotoxic chemotherapy. Recognized as the “Father of Medical Oncology,” Dr. Kennedy and several colleagues, including Emil Frei III, MD, Emil J Freireich, MD, and Paul Calabresi, MD, convinced the American Board of Internal Medicine to grant medical oncology subspecialty status in 1972, making medical oncology a strong, vibrant, and patient-focused discipline.3 The establishment of medical oncology as a respected medical discipline reverberated throughout the Western world.

Establishment of Medical Oncology in Europe

Following Dr. Kennedy’s call for the recognition of medical oncology as a legitimate medical discipline, Georges Mathé, MD, a French oncologist and immunologist, advocated for a new medical specialty in France called “internal cancerologic medicine.” This is thought to be the first proposal for the specialty of medical oncology in Europe.4

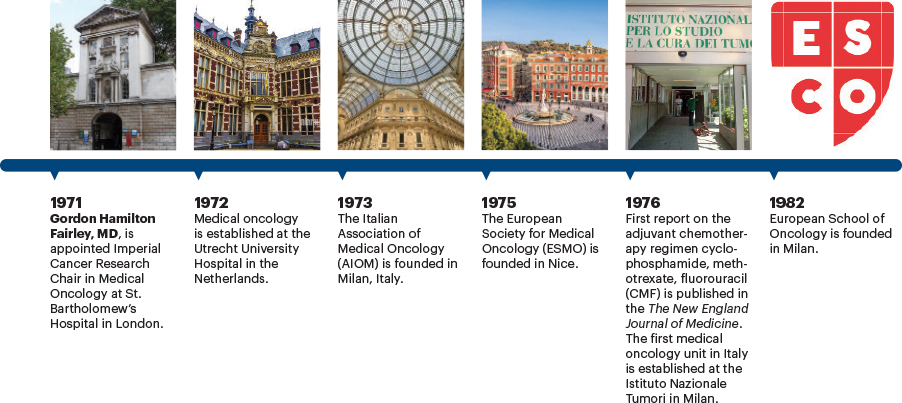

In 1973, Gianni Bonadonna, MD, considered the “Father of Italian Oncology,” defined medical oncology as a branch of internal medicine and outlined the scope of training and practice in the specialty.5 His efforts helped legitimize and structure clinical activity in oncology that had been in place for several years. Until then, physicians in charge of the treatment of patients with cancer had been labeled “chemotherapists.”

These pioneers who championed the use of the term “oncologists” were often derided, and in some instances, their idea was openly opposed by the medical establishment. Despite the criticism, the recognition of medical oncology as a specialty soon spread throughout Europe, even though training programs had not yet been developed.6 Soon after, national medical oncology societies were founded, and medical oncology as a specialty was officially recognized in most European countries.

“The importance of ESMO as a European forum for medical oncologists cannot be overstated.”— Silvio Monfardini, MD, and Lodovico Balducci, MD

Tweet this quote

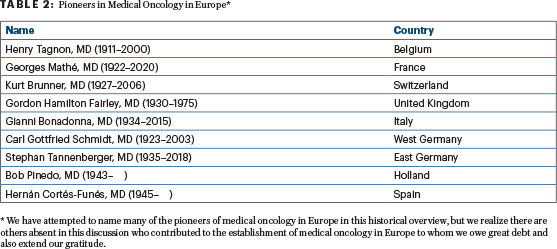

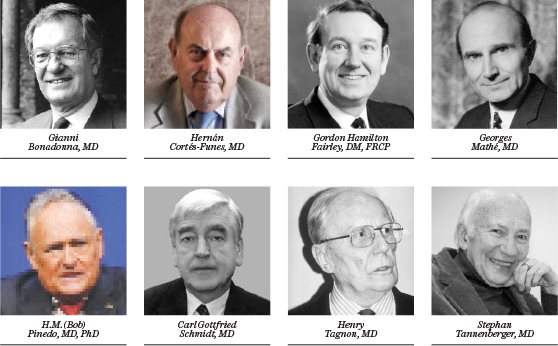

In addition to Dr. Tagnon in Belgium, Dr. Mathé in France, and Dr. Bonadonna in Italy, other early proponents of the specialty of medical oncology included Kurt Brunner, MD, in Switzerland; Gordon Hamilton Fairley, DM, FRCP, and Kenneth Bagshawe, CBE, FRCP, in the United Kingdom; H.M. (Bob) Pinedo, MD, PhD, in Holland; Carl Gottfried Schmidt, MD, in Germany; and Hernán Cortés-Funes, MD, in Spain. (Table 2). All of these investigators, most of whom were born before World War II, received their medical training in the United States prior to returning to their home countries.

These individuals fulfilled two roles of historical importance. First, they promoted medical oncology as a specialty within their own countries. Second, they established an inter-European/transoceanic cooperation that facilitated new drug development and hastened the completion of cancer clinical trials. Their efforts ultimately led to the founding of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) in 1975.

In 1978, Armando Santoro, MD, presented the results from his clinical trial on the alternating chemotherapy regimens of mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP) and doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma at the ASCO Annual Meeting. Dr. Santoro’s findings proved the effectiveness of MOPP and ABVD—now the gold standard—in the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma, surpassing his American colleagues in the race to find better therapies with less toxicity for the disease.

Role of Randomized Clinical Trials

The establishment of medical oncology in America and Europe helped foster a transnational cooperative in the development of cancer clinical research, solidifying oncology as a new form of medical and scientific practice. In their book, Cancer on Trial: Oncology as a New Style of Practice, Peter Keating and Alberto Cambrosio, PhD, detail how, since the 1960s, the advent of randomized clinical trials have formed the basis of medical oncology and have had a significant impact on advances in the treatment of patients with cancer.7

In an earlier paper, the same authors examined the historical development and articulation of the components of clinical research, including protocols, oncologists, statistics, patients, and diseases, and the new kind of objectivity they engendered.8 Today, young investigators are familiar with the conduct of phase I dose-finding trials; phase II studies to establish efficacy in a single tumor type; phase III trials comparing standards of care with potential advances in care; and phase IV studies to extend safety and activity data in a postmarketing scenario; as well as the associated statistical and ethical requirements. However, they are probably not aware of how this complex methodology developed.

In 1962, the Groupe Européan de Chimiothéarapie Anticancéreuse (GECA), now the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), was founded by four eminent European oncologists working in cancer research, including Dr. Mathé, who was President of GECA from 1962 to 1965; Dr. Tagnon; Silvio Garattini, MD; and Dirk van Bekkum, MD. The first study protocols launched by GECA, in 1966, were for the management of leukemia, lymphoma (then called hematosarcoma), and metastatic breast cancer.

These early clinical trials established guidelines for study designs, including the preferred treatment approach for each disease and the assessment of therapeutic responses and toxicities. The main goal of these guidelines was to standardize the management of common malignancies around Europe, an essential step toward the conduct of randomized controlled studies.

In proposing these transformations, Dr. Tagnon underlined how cooperative research involving multiple European countries might be more efficient and less costly than clinical trials performed in individual countries. He also introduced the concept of translational research and insisted that clinical trials should test hypotheses developed in the laboratory. (Unfortunately, this proposal remained largely an aspiration.) Since 1974, all EORTC research data have been saved in a single repository in Brussels.

During this time, the definition of phase I and II studies opened the door to new drug developments. By the time GECA evolved into EORTC in 1968, the decision was made to adopt the terminology used in the United States to delineate the purpose of the various research phases. Today, no one disputes the need for controlled randomized clinical trials to compare the efficacy of different treatment approaches. However, these types of studies have been controversial in the past.

For example, in 1970, the French medical statisticians Daniel Schwartz, Robert Flamant, and Joseph Lellouch observed in their book L’Essai Therapeutique Chez L’Homme (Statistical Methods of Physicians and Biologists) that “after some 20 years of experience, physicians, as well as statisticians, have taken stock of some limitations of their methods, noting that trials done in a rigorous way delivered conclusions that were too often ‘true’ but unusable.”9

With this observation, the authors drew attention to the difference between treatment efficacy and effectiveness. A treatment that was beneficial to a selected patient population was called efficacious. It was called effective only if it was beneficial to the general population. Efficacy was important in the sense that it proved a biologic hypothesis. For example, the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy proved conclusively that cancer is a systemic disease, even if only a portion of the population is able to tolerate and benefit from it. Phase III clinical trials established the efficacy of a treatment regimen whose effectiveness would be confirmed in phase IV studies.

Development of International Cooperative Trials

Other important controversies in the 1970s over the design of clinical trials included the use of historical control arm data for assessing treatment effects and the reliability of clinical trials conducted by cooperative groups with multi-institutional cancer clinical trials. The use of historical controls was appealing for economical, recruitment, and ethical reasons; this approach required a smaller number of patients and did not present the difficulty of enrolling and justifying the inclusion of an untreated group of patients. From the beginning of this controversy, Dr. Mathé in Europe and Dr. Freireich in the United States were strong advocates of using historically controlled studies in cancer research.

However, eventually it was recognized on both sides of the Atlantic that historical controls presented insurmountable flaws, such as stage migration, unreliable patient selection, and evaluation of therapeutic response.

Today, the cooperative trial approach is universally accepted for comparative phase III and IV studies. But prior to the organization of cooperative groups in oncology, there were legitimate concerns regarding the comparability of data obtained by different institutions. Only single-institution studies appeared to guarantee reliable data.

Between 1962 and 1974, the data collected by EORTC were registered and handled in different locations. In 1969, Maurice Staquet, MD, MS, was appointed Director of the Coordination Office of EORTC studies. That year, while attending a conference in Paris, Dr. Tagnon approached William Levin, MD, Chairman of the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Clinical Investigation Review Committee, about the difficulties facing the conduct of clinical trials within EORTC. It was apparent that France, Belgium, the Netherlands, West Germany, and Italy were all involved individually in clinical trials of new cancer agents, but there was no way to pull these efforts together and compare data obtained in the different countries.

Dr. Levin recommended the formation of an EORTC Data Center, which was eventually funded by the NCI. The EORTC Data Center, now the EORTC Headquarters, was established with the help of American experts and began operations in January 1974, led by Dr. Staquet, to coordinate phase II and III clinical trials conducted by EORTC researchers. It was the first of its kind in Europe to provide the conception, conduct, and analysis of international clinical trials.

Discovery of New Anticancer Drugs in Europe

In 1972, the NCI established a liaison office in Brussels to facilitate communications with the EORTC and the United Kingdom’s Cancer Research Campaign (CRC, which merged with the Imperial Cancer Research Fund in 2002 as Cancer Research UK) and to expedite the acquisition of compounds with potential anticancer activity from European pharmaceutical companies and laboratories. The NCI Liaison Office, headed by Omar Yoder, PhD, a familiar presence at EORTC and CRC meetings, fostered the development of a standard format for research protocols and procedure.

That same year, the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan opened an office of operations for clinical trials. The methodology and logistics of clinical trials at the institute were described in detail in a study by Drs. Gianni Bonadonna and Pinuccia Valagussa, in 1978.10 According to the authors, the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori started from the assumption that a clinical trial is a complex scientific operation involving human patients, medical facilities, and time. Its components include investigators and other medical staff, logistics, and the reliable collection of clinical data. They continued by describing the steps of a study protocol, including trial design, activation, patient enrollment, and the submission and evaluation of data. Quality control across this complex endeavor is paramount.

About 15 years later, the NCI, EORTC, and CRC agreed to form the Joint Formulation Working Party to facilitate the freer exchange or assignment of high-priority drug candidates at any stage of development to any appropriate NCI, EORTC, or CRC laboratory or clinic. The U.S. interest in new drug development in Europe can be explained by the many anticancer drugs developed in countries with a long tradition in the chemical industry. For example, the alkylating agents developed in Europe include cyclophosphamide, discovered by German scientists; and busulfan, chlorambucil, and melphalan, developed in the United Kingdom. Among the antitumor antibiotics, daunorubicin was discovered simultaneously by scientists in Italy and France, and doxorubicin, by researchers in Italy. Among the platinum analogs, carboplatin, as well as the hormonal compound tamoxifen, were discovered in the United Kingdom.

Undoubtedly, the development of clinical trials in Europe was promoted by investigators trained in the United States and involved a substantial U.S. investment of financial, intellectual, and human resources. The North American influence on the European clinical research model played a fundamental role in molding a generation of European medical oncologists.

Formation of Oncology Societies

The mid-1970s were important years for the establishment of oncology societies in Europe. In 1975, the Société de Médecine Interne Cancérologique was founded in France and had an international scope, attracting oncologists from France, Italy, Belgium, and the United States. That year also saw the founding of ESMO,11 which is headquartered in Switzerland.

The importance of ESMO as a European forum for medical oncologists cannot be overstated. Prior to the founding of ESMO, the main gathering grounds for oncologists were in the United States at the Annual Meetings of ASCO and the American Association for Cancer Research, or at meetings of the Union for International Cancer Control, which are generally held outside of Europe.

Summary

Tracing the first steps of the establishment of medical oncology as a subspecialty has been challenging. Many of the initial documents we used in our historical timeline were published in local journals and in bulletins that are not indexed in Medline, and several of the documents we located were in languages other than English. As a result, a large amount of our information was gathered by interviews with the surviving pioneers. Further, we have attempted to name many of these pioneers in this historical overview, but we realize there are others absent in this discussion who contributed to the establishment of medical oncology in Europe to whom we owe great debt and also extend our gratitude.

Undoubtedly, the creation of European medical oncology was inspired by the American experience, which is not surprising, given that in the years following World War II, the reconstruction of the European economic infrastructure took priority over medical research. The vision and the persistence of young European clinical scientists who had trained in the United States allowed Europe to follow a similar path since the beginning of the 1970s.

The pioneers of European medical oncology had to endure skepticism and derision from the medical establishment. They also had to brave serious opposition by an entrenched medical system. The heads of medicine in general hospitals did not see the need to create an additional medical specialty for oncology. As noted earlier, medical oncology was often perceived as a threat to the established disciplines of surgical and radiation oncology.

This reaction is not surprising, since open hostility to change is a common response to medical innovations. For example, it is well known that when Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis, MD, proposed, in 1846, that handwashing prior to each gynecologic exam of pregnant women could prevent puerperal sepsis, he was dismissed as a lunatic from the Vienna hospital where he practiced.

We hope this history will inspire young oncologists to overcome the inevitable obstacles they will encounter with the same optimism and determination that supported the European pioneers in medical oncology. Together with sound science, optimism and determination are the instruments necessary to prevail over suspicion, endure opposition, and achieve steady improvement in patient care.

Optimism and determination will allow modern oncologists to obtain a genomic profile of cancer that is both reliable and affordable, to weed out targeted treatment of questionable efficacy from proven life-saving therapy, and most important of all, provide all patients with comfort and compassion. The development of evidence-based palliative care has arguably been the most lasting achievement of oncology throughout the world. Death is unavoidable, but the suffering that accompanies death must be avoided. We call this goal healing, which is always available, even when disease is incurable.

Editor’s Note: See part 2 of this series on The History of Medical Oncology in Europe in related articles below.

DISCLOSURE: Drs. Monfardini and Balducci reported no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Monfardini is Chair of the European School of Oncology program on history of European Oncology, Milan, Italy. Dr. Balducci is Professor of Oncology and Medicine at the University of South Florida College of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Geriatric Oncology, Senior Adult Oncology Program at H. Lee Moffit Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Florida.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We would like to thank the following colleagues who contributed many hours of their time in the reconstruction of the history of the establishment of medical oncology in Europe, which was often provided in the absence of published material.

Silvio Garattini, MD, Former Director of the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research (1961–2018); research scientist, physician, and professor in chemotherapy and pharmacology

Maurice Schneider, MD, of the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis, Nice, Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur, France

John Smyth, MD, Assistant Principal at the University of Edinburgh; Emeritus Professor of Medical Oncology, University of Edinburgh

Peter Voswinkel, Medical Historian, German Society of Haematology and Oncology, Berlin

Dieter Hossfeld, MD, of the Medizinische Klinik, Universitätsklinikum Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Hans-Joachim Schmoll, MD, Professor of Medicine, Klinik Innere Medizin IV-Hämatologie-Onkologie, Martin Luther University in Halle-Wittenberg, Germany

Franco Cavalli, MD, Professor of Medical Oncology at the Medical Facility in Bern, Switzerland; Scientific Director, Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, Bellinzona, Switzerland

Matti S. Aapro, MD, President, European Cancer Organisation 2020–2021; Dean, Multidisciplinary Oncology Institute in Genolier, Switzerland

Alberto Costa, MD, PhD, Chief Executive Officer of the European School of Oncology

REFERENCES

1. Beatson GT: On the treatment of inoperable cases of carcinoma of the mamma: Suggestions for a new method of treatment, with illustrative cases. Trans Med Chir Soc Edinb 15:153-179, 1896.

2. The Nobel Prize: Charles B. Huggins. Available at www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1966/huggins/facts. Accessed November 12, 2021.

3. Muss HB: In memoriam: Byrl James Kennedy, MD. J Clin Oncol 23:3297-3298, 2005.

4. Mathé G: Role of the internist in clinical cancerology: The necessary service of internal cancerologic medicine in the University Hospital Center. Nouv Presse Med 1:2085-2086, 1972.

5. Bonadonna G: Definition, activity, and training in medical oncology. Tumori 59:449-454, 1973.

8. Keating P, Cambrosio A: Cancer clinical trials: The emergence and development of a new style of practice. Bull Hist Med 81:197-223, 2007.

9. Schwartz D, Flamant R, Lellouch J: L’essai therapeuique chez l’homme. The James Lind Library. Available at www.jameslindlibrary.org/schwartz-d-flamant-r-lellouch-j-1970. Accessed November 12, 2021.

10. Bonadonna G, Valagussa P: The logistics of clinical trials. Biomedicine 28(spec no):43-48, 1978.

11. Hansen HH, Bjerre-Jepson M, Hossfeld D: The European Society for Medical Oncology and its activities through the Central Eastern European Task Force. Ann Oncol 10(suppl 6):S9-S13, 1999.