A clinical dilemma that is receiving a great deal of attention in the oncology community is the undue financial burden some patients face during their treatment and into survivorship. While much emphasis is put on methods to reduce and help patients navigate the complex payment system, little is known about patient attitudes toward cost considerations influencing treatment decisions.

To bring clarity to this important issue, The ASCO Post spoke with Barry R. Meisenberg, MD, Medical Director of the Geaton and JoAnn DeCesaris Cancer Institute at the Anne Arundel Medical Center, a Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network–affiliated regional health system headquartered in Annapolis, Maryland. Dr. Meisenberg recently conducted a study on this question.

Current Role

Please describe your current work as Medical Director of the Geaton and JoAnn DeCesaris Cancer Institute.

I’m a hematology-oncology clinician and outcomes researcher. Thirty percent of my time is spent seeing patients. I do program building for patients with cancer here at the Cancer Center, and I handle the typical administrative and operational duties that a medical director of a cancer center is charged with. I’m also the Chair for Quality Improvement and Healthcare Systems Research at Anne Arundel Medical Center.

Two Financial Issues

What was the goal of your recent study?

To begin, like many in the oncology community, we’re concerned about the financial burden on our patients. To that end, we were thrilled when in 2013 the term “financial toxicity” was first described because it crystalized what the issues were. In that term lies the concept that some of the financial toxicity might be ameliorable. In our study, we first sought to determine how prevalent financial stress was among our cancer patients, and then we wanted to know what our patients wanted to do about it.

There hasn’t been much research looking at these two issues in combination. As early as 2009, ASCO came up with a guideline recommending that physicians discuss cancer costs with patients. Many surveys indicate that patients want to be told about the costs of their cancer care early in the treatment cycle.

Patient Attitudes

What do your data tell us about patient reactions to these conversations?

Some data suggest that patients welcome a cost conversations with their oncologists but don’t insist on it. However, our study data indicated that patients did not want to have discussions about costs—either to society or themselves—because that might influence treatment decisions.

We conducted the survey in the summer of 2014. It was a convenience survey—a nonprobability sampling technique whereby the researcher solicits opinions from “convenient” subjects—and we recognize that this model has limitations, but it is similar to other studies in this area of inquiry. We used an instrument called a Personal Financial Wellness Scale, which is an eight-item validated scale that assesses participants’ perceptions about their personal financial situation.

As it turned out, we had an entirely insured patient population, but they still had high levels of financial concerns and burdens. Interestingly, this finding didn’t necessarily correlate with income level. Even high-income families can have significant treatment-related financial stress. Some of these reactions might stem from generalized fear, but cost burden is not relegated to low-income patients.

Impact on Treatment Decisions

How did patients in your study feel about tailoring treatment decisions to prevent undue financial stress?

Our patients strongly disagreed with the idea of altering treatments according to costs—either society’s or their own out-of-pocket. That finding is similar to other studies, such as one by Andrea J. Bullock, MD, and colleagues in 2012.1 So our finding wasn’t new.

When we narrowed the question down to whether their personal finances should be factored into the treatment decision-making, once again, they strongly disagreed with that notion. Then we asked the study group: If you were to see that the treatment options were similar in efficacy, would you then want your therapy to be based on cost. A slightly larger minority of patients said yes, but the plurality still said no.

Underlying Thought Process

Did you come to any conclusions about why patients are strongly set against factoring costs into their treatments?

Although these data need to be verified, the findings indicate that patients are not cost-sensitive, even when it comes to their own out-of-pocket costs. The clinical importance is that in any discussion about costs we have with our patients, we need to know where their attitudes come from. The study gave some direction in that regard.

We speculated that there might be a bias toward new and more expensive therapies, equating novelty and higher costs with better results. This finding is similar to the way consumers conceptualize higher prices with better-quality products.

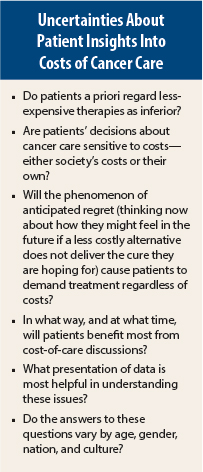

There’s also a phenomenon called anticipated regret (see sidebar),2 which proposes that when facing a decision, individuals may prepare for the possibility of feeling regret after the uncertainty is resolved and, thus, incorporate in their choice a desire to eliminate or reduce this possibility.

Also—and this is important for our professional society—advertising by drug companies and cancer centers creates the illusion that there are miracles waiting. This, in turn, creates a medical consumer trend of wanting a specific treatment or drug no matter what it costs. To that end, at our institution we are very careful in our marketing techniques, and we are equally cautious about how we talk about advances in treatment.

End-of-Life Care Discussions

Do you feel that the recent decision by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to reimburse physicians for discussions about end-of-life care fits into the general theme of trying to avoid financial toxicity?

The issue of cancer patients requesting expensive, aggressive end-of-life care even though it doesn’t offer cure and often doesn’t enhance quality of life, is much more complicated than a CMS reimbursement policy. I agree with those who don’t think lack of reimbursement to be a barrier to the important and difficult discussions with advanced cancer patients.3 It is a professional responsibillity. Personally, I think the reimbursement issue is a distraction from the larger issues. The ASCO value framework may facilitate those discussions.

There was a terrific paper on a CanCORS study led by the late Jane Weeks, MD, MSc, looking at 1,193 patients, which found that 69% of patients with lung cancer and 81% of those with colorectal cancer did not report understanding that chemotherapy was not at all likely to cure their cancer.4

These data from our study and others looking at this issue behoove the oncology community to develop and test better tools to explain the complex interactions of cost and clinically meaningful outcomes. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Meisenberg reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, et al: Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract 8(4):e50-e58, 2012.

2. Meisenberg BR: The financial burden of cancer patients: Time to stop averting our eyes. Support Care Cancer 23:1201-1203, 2015.

3. Halpern SD: Toward evidence-based end-of-life care. N Engl J Med 373:2001-2003, 2015.

4. Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al: Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 367:1616-1625, 2012.