Evidence indicates that the use of surgical safety checklists results in marked improvements in patient outcomes. Unfortunately, their adoption in the field of medicine has largely been limited to equipment operations or parts of specific treatment algorithms. Yet they have tremendous potential to improve patient outcomes by democratizing knowledge and helping ensure that all patients receive evidence-based best practices and safe high-quality care.

That said, not all checklists are created equal, and the development and use of this simple tool are more complicated than it would appear. The value and proper use of checklists were fully examined at this year’s Quality Care Symposium by William Berry, MD, MPA, MPH, FACS, Principal Research Scientist, Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.1

“I want to spend time talking about a decades-long journey I’ve been on with several colleagues, which has led to a better understanding about how to use checklists for quality improvement. And I believe there is a place for a checklist or a standardized protocol when delivering chemotherapy, especially in the oral administration setting,” said Dr. Berry.

Learning From Disaster

To illustrate the potential consequences of missing a protocol step, Dr. Berry took the audience back to the early 1930s. At that time, the U.S. Army Air Corps was looking for a multiengine bomber that had greater capacity and range to replace the old Martin B-10. Boeing won the contract and designed and built the B-17 bomber, known as the Flying Fortress. On October 30, 1935, with Boeing’s two best test pilots at the controls, the B-17 rolled down the runway on its second test flight before a crowd of reporters.

When the huge plane lifted off the runway, it stalled, nosed over, and crashed in a ball of fire, killing the two pilots. It was discovered that the crew had forgotten to disengage the “gust locks,” a system of devices that are locked in place while the aircraft is parked on the ground but must be unlocked before takeoff to avoid the kind of disaster that befell the B-17. Subsequently, the use of preflight checklists became standard procedure by military pilots and was later adopted by all commercial pilots.

Enhanced Patient Outcomes

The checklist didn’t stop with the airline industry. Dr. Berry pointed to the famous intensive care checklist developed by Peter J. Pronovost, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, that experts say has saved countless thousands of lives and hundreds of millions of health-care dollars. “Checklists are now spreading more broadly throughout medicine, particularly for certain settings where they are very useful and enhance patient outcomes,” said Dr. Berry.

He continued, “I think you can use checklists to change workplace policies, improve your patient care process, enhance teamwork and communication, and help guide a conversation among your colleagues.” He added that checklists standardize and improve the reliable translation of information so that the same knowledge is available to doctors, nurses, and patients.

Know When and Where to Use Checklists

Dr. Berry then drilled down to the specific strongpoints of the checklist. “If a task has a lot of important steps, which increases the possibility of accidently omitting one, a checklist becomes an important tool. Moreover, tasks that are performed under stress can benefit from a checklist because people working under stress are more likely to forget an important item, which can prove fatal in certain patient care settings. Checklists are also useful for reminding people to do new things that have recently been integrated into the patient care path,” said Dr. Berry.

Dr. Berry explained that there are places where checklists should not be used. “Checklists aren’t particularly valuable as a learning tool since we don’t absorb complex information in that kind of linear fashion. Also, checklists by their very nature are designed for simplicity; they don’t take the place of algorithms or procedure guides that are needed in highly complex scenarios,” said Dr. Berry.

He explained that there are two basic kinds of checklists. “There is a read-do checklist, which means that you read through the checklist while you’re doing the task. And there is the read-confirm checklist, in which one party of the medical team reads a point off the list, and it is verbally confirmed by another team member,” said Dr. Berry.

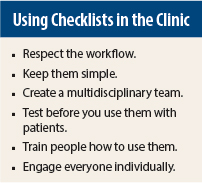

“I look at checklist development in several major phases and virtually every quality improvement measure addresses these phases. In the first phase, you need to be focused on the steps you want integrated into your tool. Then comes the tool-making part, when you actually draft the document. The most important step here is to keep it as simple as possible. No one should have to work off a six-page checklist. And probably the most important aspect of making a checklist is to test it in the clinical setting it’s designed for before finalizing it as a document,” stressed Dr. Berry.

Practice Is Needed

Dr. Berry noted that a checklist by itself is just a piece of paper, and proper training is essential to making it a valuable tool in the clinic. “Actual practice using the checklist away from the patient setting is the best way for people to learn. Repetitive workshops during which the checklist is used also creates a good communication base for the care team,” said Dr. Berry, adding, “Collecting feedback and learning about what works well is essential for long-term use.”

Dr. Berry’s presentation concluded with a simple takeaway message. “The one idea I want to leave you with, which might seem patently obvious, is that if you want someone to use this tool, have a one-on-one conversation with him. Don’t send out e-mails or tweet about it. That works for some ideas but not this kind of hands-on tool. If you want people to change their behavior in the clinic, it is important to have a personal conversation with them.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Berry reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Berry W: Patient safety across disciplines: Checklists (surgery). Quality Care Symposium. Presented October 18, 2014.