In this installment of The ASCO Post’s Global Oncology series, Guest Editor Chandrakanth Are, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FACS, spoke with Ahmad Bashir Barekzai, MD, FACS, Consultant Surgical Oncologist at Ali Abad Teaching Hospital, an affiliated hospital to Kabul University of Medical Science, Kabul, Afghanistan. Built in 1931, under the direction of Afghanistan’s king Muhammad Nadir Shah, the Ali Abad Hospital is the nation’s oldest hospital, originally created to address the tuberculosis epidemic that ravaged the country. Although it was severely damaged during the civil war that tore Kabul apart in the 1990s, Ali Abad Hospital was restored and is currently a 250-bed teaching hospital.

Ahmad Bashir Barekzai, MD, FACS

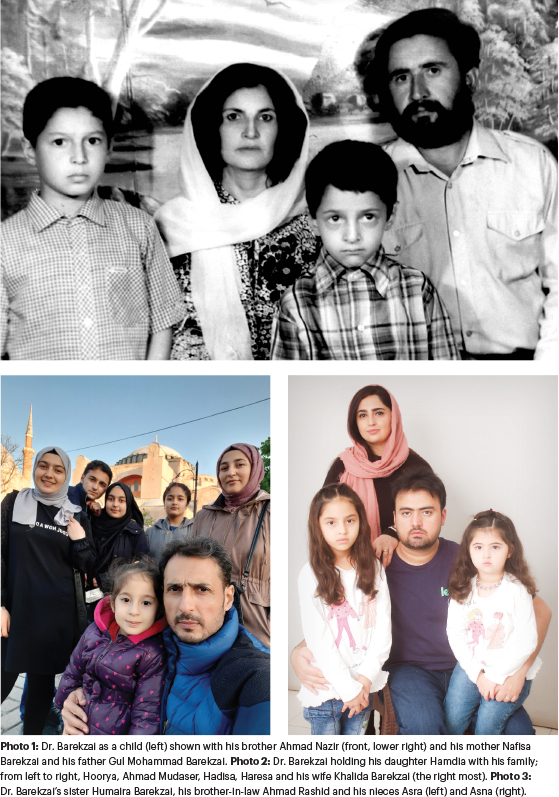

A Family Reshaped by a Sniper’s Bullet

In 1979, the then Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, precipitating a bloody, 10-year war with Afghani fighters (Mujahidin), during which upward of 2 million Afghanis died. “I was born 3 years after the Soviets invaded our country,” remembered Dr. Barekzai. “Our family lived in a small village close by the capital city of Kabul. My parents, my brother, and I shared a house with my grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, so it was a large family setting. Things were difficult during the war, especially for the educated class, who came under suspicion by both the Soviet-supported government and Mujahidin as well.”

Dr. Barekzai continued: “When I was in 3rd grade, we moved to a more civilized part of the city of Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. It was then that my sister was born, and our family became five. When I was in 7th grade, Dr. Najibullah’s government collapsed, and Mujahidin occupied all parts of Afghanistan including Kabul. That’s when the war between Mujahidin troops started all over the country, especially in Kabul, where fighting was fierce. This war ruined most of Kabul, its infrastructure and public properties. There was a point when a cease-fire occurred, but it was short-lived; during that period, perhaps because we let our guard down and went outside to play, my younger brother, who was in 4th grade, was shot in the neck and killed. Despite the cease-fire, the military troops were firing into the air, and one of those bullets killed my brother.”

He added: “And that was when the war exploded again, all over Kabul. My father was an engineer, and my mother was a teacher, both government employees. With the fighting, we moved out of Kabul, traveling to other provinces, even into Pakistan, where we lived in immigrant camps. However, when the war slowed down, we moved back to Kabul, as my parents needed to work for the government and support the family.”

Educational Challenges

Dr. Barekzai excelled in school, particularly in math and science. Two educational systems exist in parallel in Afghanistan. Religious education is the responsibility of clerics at mosques, and the government provides free academic education at state schools. From ages 7 to 13, pupils attend primary schools, where they learn the basics of reading, writing, arithmetic, and their national culture. Then, 3 years of middle school follow, where academic-style education continues, and finally, 3 years of high school. For further higher education, students must take an entry exam called Kankor.

When Dr. Barekzai was in 12th grade, preparing for college, the Taliban gained control over Kabul and the neighboring regions, imposing harsh religious strictures, one of which forbade girls from attending school. “It was another difficult period for us, but fortunately, I passed the entrance exam for medical school and entered the Kabul University of Medical Sciences (KUMS) in 1998,” he shared. Dr. Barekzai explained that medical school in Afghanistan is a 7-year program (with some delays in recent years due to conflicts, war, elections, and so forth). The first year is known as MPCB, which is intensive training in math, physics, chemistry, biology, statistics, and English language studies. The next 5 years are devoted to medical training in the classroom, lab, and clinic, and the final year is an in-house internship at different KUMS-affiliated hospitals in different parts of Kabul.

“During this period, I became engaged to a woman who was part of our extended family and was living in a refugee camp in Pakistan. The Taliban had taken firm hold by then; but when I eventually went to Pakistan to marry my fiancée (because music and fun were not allowed in Afghanistan, and these are inseparable parts of a wedding ceremony), the international forces entered Afghanistan and drove the Taliban out of Kabul. So, we returned, and I resumed medical school, attaining my medical degree in 2005. I am now the proud father of four girls and one son, and we live in Kabul along with my mother and father,” said Dr. Barekzai.

A Decision to Pursue Surgical Oncology

Asked about his journey after medical school, Dr. Barekzai responded: “Working at different hospitals during internship—especially the Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital, where I worked for 3 months during my internship—had a profound effect on my career. The pediatric surgeons were very helpful in our training. We were there assisting them, but, in reality, they were assisting us, too. So, during the 3 months I was assisting pediatric surgeons, my mind changed 180 degrees and I left all my preconceptions behind. (I had initially intended to become a cardiologist.) Seeing the way the surgeons dealt with patients, I decided to become a surgeon myself. When I finished medical school, I went to work in a small private clinic, where I practiced as a general practitioner in general surgery and laparoscopic surgery. And then I decided to better my skills as a surgeon, I’d have to venture to a place where there were more high-volume procedures,” he explained.

Guest Editor

Chandrakanth Are, MBBS, MBA, FRCS, FACS

Fortunately, two of Dr. Barekzai’s close friends, both 1 year senior to him in medical school, who had gone to India to work in general, laparoscopic, and oncologic surgery, encouraged him to go to India for training, so he could better serve the challenges at home in Afghanistan.

“When I went to India, I joined a team of surgical oncologists headed by Dr. Sameer Kaul at Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi, as a fellow. I got involved in multiple complicated cases being treated by members of that team, became more interested, and continued my training as a fellow in surgical and clinical oncology. And at the end of 2007, I came back to Kabul and passed the entrance exam; shortly after, I began working in the general surgery residency program at Aliabad Teaching Hospital in 2008. It was a 5-year program, which I finished in 2013,” Dr. Barekzai said.

“During the residency, I attended many courses and conferences in India, went to Germany for a 3-week general surgery training course, as well as Egypt and China to attend IASGO conferences [International Association of Surgeons, Gastroenterologists and Oncologists], and three times in different years for short courses and observerships to Turkey,” he said. In the same year, 2013, he was accepted as a consultant surgical and clinical oncologist in the oncology department of Aliabad Teaching hospital and since then practicing in both government facilities and the private sector. In 2014, I spent 3 months with the hepato-pancreato-biliary service in the surgery department at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, as a clinical research fellow. It had a huge impact on my knowledge in patient care and oncology practice. I will never forget the support and dedication of my mentors, Dr. Murray F. Brennan, Dr. William R. Jarnagin, and Dr. Peter Kingham.

Delivering Cancer Care Without Radiation Therapy

Armed conflict in Afghanistan has continued for close to 40 years and has devastated its health infrastructure. The lack of a cancer care infrastructure has meant that many Afghans must seek cancer care in neighboring countries, such as India, Pakistan, and less often, Iran.

Asked about his current work schedule, Dr. Barekzai replied: “As I did a fellowship in surgical and clinical oncology and finished my residency in general surgery as well, I am taking care of both oncology and general surgery patients, but the majority of my practice is related to oncology. We don’t have such a specialized oncology care system in Afghanistan—unlike in the West, where the field is divided into three disciplines of medical, radiation, and surgical oncology. In fact, we don’t have a single radiation oncology facility in Afghanistan, so my work is a combination of medical and surgical oncology. My routine is no different from that of other surgeons; it includes educational activities, ward rounds, outpatient clinic, operations, ICU care, and so forth. The only difference is that I am giving chemotherapy to my patients as well. It is a challenging clinical setting, but we do the best we can, given our limited resources.”

Dr. Barekzai continued: “At one time, many years back, we had a cobalt-60 radiation treatment unit in Aliabad Teaching Hospital. However, during the war, the radiotherapy machine and its facility were destroyed. After that, due to the continuing war, and in recent years due to security concerns, Afghanistan could not start a nuclear medicine program or radiation therapy services. As an example, we have neither bone scan nor PET scan capabilities (given that they are very expensive and require a nuclear medicine program), which, of course, makes the delivery of cancer care that much more difficult.”

How many other surgeons are there in Afghanistan like you, Dr. Are asked. “In spite of war and many other problems that the Afghan people have faced, we have a lot of very competent surgeons, experts in their field, in every part of Afghanistan taking care of patients. However, there are just a handful of officially trained surgical oncologists.

Sizable Challenges to Cancer Care

The Sehatmandi Project is the backbone of Afghanistan’s health system, run by the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) with cooperation from international organizations and providing care for millions of people through 2,331 health facilities. Jamhuriat Hospital is one of the MoPH-run hospitals, which in recent years started providing oncology services. Since the Taliban gained power, major funding for the program has been withdrawn. Moreover, according to a report by the United Nations World Food Program, just 5% of households in Afghanistan have enough to eat every day.

“The time lapse from diagnosis to treatment is a serious challenge, as people must travel significant distances to reach a clinic for basic health problems and much farther distances to reach Kabul for oncology care. This is made more difficult by our infrastructure, which was damaged severely during the war. The second challenge is the poor economic state of patients, even though there is government assistance, as well. It is obvious that the cost of cancer therapies is very high, even posing challenges to wealthy nations like the United States, so one can imagine the challenges to a poor country such as Afghanistan,” said Dr. Barekzai. “There is also a huge awareness issue. Many people in Afghanistan believe that cancer is incurable and that a cancer diagnosis is a death sentence, so they don’t bother with follow-up services. The next problem is a lack of screening facilities and early detection programs, which all lower-income nations face. So, we have a host of challenges to our cancer care system. We must approach it piece by piece, otherwise the challenges are overwhelming.”

There is also a huge awareness issue. Many people in Afghanistan believe that cancer is incurable and that a cancer diagnosis is a death sentence, so they don’t bother with follow-up services.— Ahmad Bashir Barekzai, MD, FACS

Tweet this quote

Cancer Burden and COVID-19

Dr. Are shifted the conversation to the global perspective. He asked whether there are data to quantify Afghanistan’s cancer burden, and Dr. Barekzai responded: “We don’t have a robust and accurate data collection system. But if you ask anecdotally about my practice, and my colleagues’ practices, we see more cases of esophageal cancer as well as cancers of the breast, stomach, colon, and gynecologic cancers. And, again, our biggest challenge remains economic; when people are economically challenged, it exacerbates all public health issues, including cancer.”

As for COVID-19, there has been no apparent effect in Afghanistan, especially in terms of patients with cancer. Dr. Barekzai continued: “We just canceled chemotherapies and planned surgeries for 1 or 2 weeks during the peak COVID-19 wave. For one, this is because most people in Afghanistan don’t believe COVID even exists. Our patients with cancer want their treatments; they are concerned with cancer, not COVID. So, our people’s perception of the world is far different from that in the West. When the coronavirus pandemic was halting operations in other places, my colleagues and I just came back to the hospital and began taking care of our patients with cancer. That was our priority,” he explained.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Barekzai reported no conflicts of interest.