It was February 1996, and the first annual meeting of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) was drawing to a close, when Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Bruce R. Ross, MD, invited comments from the floor. An oncologist who had attended at the urging of a friend—somewhat reluctantly—stood up.

“I came here,” he said, “wondering who are these people who have the nerve to tell me how to practice? I’ve been practicing for decades!” Then he added: “But I have to tell you, this is the most incredibly important meeting I’ve been to in many years.”

Robert W. Carlson, MD

Twenty-five years later, it’s not hard to understand that change of mind. Those first guidelines, like all that followed, did not dictate. They offered guidance and direction, but they were open to comment and discussion. “What was presented,” said current NCCN CEO Robert W. Carlson, MD, “were the first versions of guidelines, which have always been dynamic and evolving documents.”

The nature of that meeting, where first versions were presented and comments were welcome, points to another hallmark of the guidelines from the beginning: transparency.

“We emphasize transparency,” Dr. Carlson wrote in an e-mail interview. “That includes transparency of the standard procedures that the panel and staff follow in developing NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®); transparency of panel members and their specialties and any financial conflicts of interest; transparency of data used to make recommendations via a fully referenced manuscript; the inclusion of categories of evidence and the degree of consensus associated with recommendations; and the categories of preference that highlight the panel’s preferred choice among multiple options.”

The same principle applies to the NCCN Evidence Blocks™, which score the efficacy, safety, and quality of available data; information provided on the consistency of the available data; the affordability of what is recommended; and the transparency of funding sources for any activity that can influence the content of the guidelines.

Those hallmarks of the earliest years—guidance and transparency—are evident in the products and working culture of the NCCN as it evolved over the next 25 years.

The Beginnings

It all started in the early 1990s, a time of rapid increases in health-care costs. “It was a time of upheaval in medical care,” Dr. Carlson wrote, “with the advent of health maintenance organizations, managed care, and capitation. A lot of the academic cancer centers did not have enough resources to do much training or research. And patients did not always have access to more complicated treatments.”

It was also a time when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other payers were exploring ways to reduce costs. One CMS proposal in those early years was to redirect patients to community hospitals, rather than academic centers.

Joseph V. Simone, MD, FASCO

“That caused an uproar among academic centers of all kinds,” recalled Joseph V. Simone, MD, FASCO, then Physician-in-Chief at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Writing in a guest editorial in JNCCN—Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, he added: “I became deeply involved in trying to deal with the potential changes.” After conferring with leaders in other academic cancer centers, “a few of us came to believe that we should promote the attraction of higher-quality care.”1

Among those leaders was Charles M. Balch, MD, FACS, FASCO, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. He and another of the early founders, Catherine Harvey Sevier, DrPh, RN, AOCN, chronicled NCCN’s first steps in a recent article.2

Charles M. Balch, MD, FACS, FASCO

Catherine Harvey Sevier, DrPh, RN, AOCN

“NCCN was conceptualized in 1992 and 1993,” they wrote, “after several confidential phone calls to explore setting up a national managed care network. The leadership group included [in addition to Drs. Simone and Balch] James S. Quirk, who was Senior Vice President for Research Resources Management at Memorial Sloan Kettering; John R. Durant, MD, FASCO, President of Fox Chase Cancer Center; his Executive Vice President, Francis J. McKay; Robert C. Young, MD, FASCO, of Fox Chase, and Michael D. Goldberg, MBA, who brought in [Dr. Sevier] as a consultant and the first paid staff member.”

Early Years

NCCN was officially incorporated in 1993. At a meeting in Chicago in 1994, a Statement of Principles was promulgated, defining NCCN as a national alliance of cancer center providers, organized “to develop and institute standards, guidelines, and systems that assure high-quality, cost-effective care.” On January 31, 1995, the fledgling network, with 13 member institutions, made its public debut at a press conference at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

“The response from members of the press seemed to be bemused interest,” recalled John A. Gentile, Jr, writing years later in a JNCCN guest editorial.3 [Mr. Gentile is Chairman of Harborside, the publisher of The ASCO Post; Harborside also has a publishing arrangement with the NCCN for JNCCN.] In fact, “most people thought it wouldn’t happen,” he said in an interview. “The cancer centers, after all, were competing with each other, so to think that they could come together and work as one was hard to believe.”

John A. Gentile, Jr

Mr. Gentile, then publisher of the journal Oncology, was intrigued; “I was floored,” he said, “and fascinated by the whole concept.” Soon after, he approached Drs. Simone and Harvey and offered to publish the guidelines in Oncology. And not long after that, his company, PRR, Inc, suggested introducing the new guidelines at an NCCN-centered conference.

Both ideas were accepted and integrated into the planning process as work got underway on many fronts. “The energy among members during this time was palpable,” Drs. Balch and Sevier wrote. “We knew we were creating something that could impact the quality of care for people with cancer…. All of the member representatives had full time responsibilities at their institutions, yet simultaneously put in many hours developing templates, structures, and tools.”

Rodger Winn, MD (deceased)

Organizational structure and governance mechanisms were established under the leadership of Dr. Simone, Dr. Sevier, and James Quirk. Rodger Winn, MD, of MD Anderson, oversaw development of the guidelines, and Jane C. Weeks, MD, MSc, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, began work on a strategy to measure clinical outcomes. As Chief Operating Officer, Dr. Sevier led the effort to develop and implement marketing and public relations strategies and also worked with Peggy A. Means, MHA, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, on ways to negotiate and broker managed care contracts.

In 1996, NCCN held its first annual meeting in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where it presented the first versions of guidelines to an audience of more than 400. Among them were guidelines for breast cancer, significant not only as a first, but as a demonstration that the new alliance could deal with, and survive, controversy. Dr. Carlson, who chaired that panel, remembers the discussions vividly:

“The first version of our guidelines did not include bone marrow transplants (BMT),” he wrote in the e-mail interview, “and the panel received very strong and vocal criticism from many in the medical community, including some from member institutions and on the Board of Directors. In response, the breast cancer panel met with bone marrow transplant experts from member institutions to discuss the issue.”

Dr. Carlson continued: “To put it mildly, that was a lively, spirited, contentious, and passionate meeting. The BMT community had the equivalent of real-world evidence that transplant was superior to full-dose chemotherapy. The breast cancer specialists were concerned that the apparent superiority of BMT was based upon selection bias of healthier patients and comparisons with historical controls.”

In the end, bone marrow transplant was not recommended, but the panel agreed to include footnotes stating that participation in clinical trials of BMT was especially important to consider in certain circumstances.

Those early guidelines were a landmark in still another way: “The refusal of the panel to bend to external forces was, in fact, a defining moment in NCCN history,” wrote Dr. Carlson. “The independence of the panels and their insistence on objective evaluation of evidence was demonstrated. Science trumped bias and economics.”

Another key development at this time was the decision to make the guidelines freely accessible and downloadable on the NCCN website. It was a “visionary decision,” Dr. Carlson wrote, “a policy that became an important factor in NCCN’s success, facilitating the use of the guidelines and establishing them as the go-to guidelines.”

Also established in these early years was the nature of the guidelines themselves under the leadership of Dr. Winn. His concept of, and influence on, the guidelines was described in JNCCN by William McGivney, PhD, who served as CEO from 1997 to 2011.

William McGivney, PhD

“Dr. Winn had a vision of using experts to integrate the evaluation of available scientific evidence with the experience and expert judgment of clinicians to provide recommendations for treating patients with cancer along the full continuum of care,” said Dr. McGivney. “His genius was manifest in the establishment of a process that recognized need for an evidentiary basis for the recommendations. However, Dr. Winn also understood the critical value and need for expert clinicians to provide input into the process based on extensive experience and expansive expertise.”4

Implementation of the Guidelines

As NCCN began producing more guidelines and updating earlier ones, member institutions began to turn to questions regarding implementation, ie, how to weave the guidelines into everyday practice?

At NCCN’s fourth annual meeting in 1999, this was clearly a concern. “It is a massive undertaking,” said one speaker, John L. Wilson, PhD, Director of Outcomes Management at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center–James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute. He and others described administrative strategies to facilitate use of the guidelines, such as having relevant guidelines accompany each patient’s chart.

John L. Wilson, PhD

Leaders at Oncology recognized that implementation of the guidelines posed a challenge and began to publish not only the guidelines themselves and information on how they were created, but also articles on related issues, including methods used to integrate the guidelines into everyday practice. That policy was continued when JNCCN assumed publication of the guidelines. The inaugural issue of NCCN’s own journal appeared in January 2003, with Dr. Winn serving as Editor-in-Chief.

“The mission of this new and exciting journal,” Mr. Gentile wrote, “was to publish not only the NCCN Guidelines, containing the latest information about best clinical practices, but also articles discussing the full range of oncology care, including outcomes and new research initiatives.3

Dr. Winn was succeeded by Hal Burstein, MD, PhD, FASCO, in 2008. In 2012, Dr. McGivney was able to write that the journal “has become inextricably woven into the fabric of NCCN Guidelines development and the communication process for the Guidelines and other NCCN information products.”4

During the early 2000s, economic factors were also beginning to bear on implementation of the guidelines. More payers, drawn by the predictability that the guidelines provided, were taking heed. In 2008, UnitedHealthcare decided to recognize and apply the NCCN Drugs & Biologics Compendium (NCCN Compendium®), which includes all guideline recommendations related to drugs and biologics as the full basis for insurance coverage of these agents.

That milestone was followed soon after by the decision by CMS to recognize the NCCN Compendium as a mandated reference for coverage in the Medicare program. CMS also recognized JNCCN as an approved appropriate reference journal for decision-making by Medicare contractors for local coverage determinations and by CMS itself.

The impact of the guidelines on costs continues to be significant. A 2017 study by UnitedHealthcare, eviCore, and the NCCN showed that a computer-based decision support system, designed to guide providers in the delivery of care concordant with the NCCN Guidelines, resulted in a 20% relative reduction in the cost of systemic therapies and decreased the frequency of retrospective denials of coverage.5

Outcomes Research

Another support for implementation was the NCCN outcomes database. Speaking at the 1998 annual meeting, Dr. Weeks described its purpose as, first, to provide information on adherence to the guidelines and, second, to contribute data on the value of specific interventions.

The database began with breast cancer, and in the following years, it added more cancer types. “It was a scientific success,” Dr. Carlson wrote. “With well over 100,000 patients in it, it was a rich source of patient data on a variety of cancer types for concordance analysis and research.”

Maintaining the database required large numbers of data managers in the cancer centers, and as costs became prohibitive, it was suspended in 2013. The concept, however, is very much alive. In search of a fiscally responsible way to maintain an outcomes database, the NCCN is now working with Flatiron Health, an oncology database company, to develop a new NCCN Quality and Outcomes Database.

The system is more cost-efficient, with the ability to transmit data between cancer centers’ computers and Flatiron’s computers. “Currently, there are four, soon to be six, NCCN institutions participating,” Dr. Carlson wrote. “A number of studies and publications have already resulted from this initiative.”

Still Going Strong

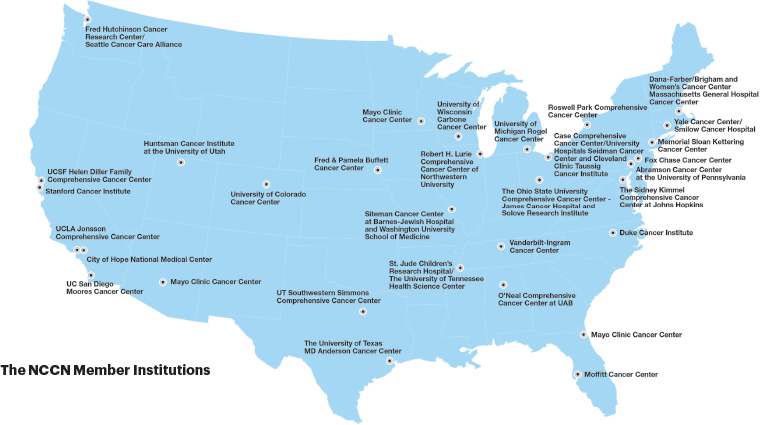

The organization that “most people thought wouldn’t happen” 25 years ago, now has 30 member institutions and 60 expert panels producing and regularly updating guidelines for 76 different conditions. In 2019, its guidelines were downloaded more than 11 million times. About 47% of users are international professionals, and there are more than 25 global adaptations and 176 translations representing 19 languages.

The NCCN also maintains a separate website for patients, which houses the evidence-based clinical guidelines tailored to the average individual, so patients can have access to the same treatment information being used by their doctors. The NCCN website for patients received 13.8 million page views in 2019.

The list of NCCN products and initiatives goes on, suggesting the story of the NCCN will continue to unfold. For more information about the NCCN’s activities, see https://www.nccn.org/about/pdf/NCCN_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Carlson is Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the NCCN. Dr. Simone was the first Chair of the NCCN Board of Directors and was instrumental in the organization’s founding. Dr. Balch was a founding member of the NCCN Executive Committee. Dr. Sevier was Chief Operating Officer of the NCCN from 1994 to 1996. Dr. McGivney served as NCCN CEO from 2007 to 2011. Mr. Gentile is Chairman of Harborside, the publisher of The ASCO Post; Harborside also has a publishing arrangement with the NCCN for JNCCN.

REFERENCES

1. Simone J: The birth of NCCN. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 13:7, 2015.

2. Balch CM, Sevier CH: Origins of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 18:499-502, 2020.

3. Gentile JA Jr: The history of NCCN and JNCCN. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 13:1173-1174, 2015.

4. McGivney W: JNCCN at 10. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 10:4-6, 2012.

5. Newcomer LN, Weininger R, Carlson RW: Transforming prior authorization to decision support. J Oncol Pract 13:e57-e61, 2017.