This is the story, told through their own photographs, of a group of adolescent patients with cancer in their search for happiness. Their images relay their hopes and fears, their desire to be normal, and their urge to escape. These photographs are the outcome of a creative arts–based support initiative organized by the Youth Project at the pediatric oncology unit of the Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan, Italy.1

Along with clinical aims, one goal of the Youth Project is to provide initiatives and spaces where young patients can regain a sense of normalcy. Held in a dedicated room specifically for adolescents at the pediatric oncology unit, creative projects generally last several months, with weekly meetings coordinated by professionals.2,3 Previous projects have focused on writing and recording songs,4,5 creating a fashion collection,6 and teaching creative writing.4 They have involved adolescent patients receiving treatment as well as those who have completed their courses of treatment. The Youth Project helps these patients communicate emotions triggered by the traumatic experience of cancer—an experience that can sometimes be difficult to put into words and may be easier to express through a song or photograph.7,8

Behind the Lens

From autumn 2015 to summer 2016, 30 adolescents and young adults took part in a photography project coordinated by Paola Gaggiotti (the artistic director of the Youth Project), during which 3 professional photographers (Alice Patriccioli, Veronica Garavaglia, and Donata Zanotti) taught them how to use a camera. They learned about exposure times and apertures, the rule of thirds, and backlighting; how to take high-quality photographs with a smartphone; and how to edit their photos with computer software. The professionals gave the patients guidance on how to develop their own projects, helping them to express their feelings through their images, to capture their experiences through an enduring medium, to have fun with photography, and to tell their stories.

As in other Youth Project schemes, the main theme was proposed by the patients themselves. They chose Searching for Happiness, a topic of particular gravity when considered from a room at the pediatric oncology unit of a cancer center. The patients worked on their own personal experience, trying to explain through their images what happiness meant to them at this particular time in their lives and what gave them strength to fight their disease and keep smiling.

The young people’s search for happiness took shape in two different directions: one involved seeking escape; not thinking about their disease; finding happiness in the normalcy of daily life (a normalcy of which they had been robbed by the diagnosis and treatment of their cancer). The other focused on the disease as a starting point for revisiting the entire concept of happiness.

Many of the patients’ photographs concerned their travels, friends, fast cars, the natural world, as well as their parents and grandparents. In the notes accompanying their photographs, some patients associated happiness with “winter sunshine,” “hot coffee in the morning,” “mum’s lasagna on Sundays,” “the smell of chocolate,” and “lying on the sofa listening to music.” Other comments offered evidence of a remarkable awareness; happiness was defined as “having a life to live,” “having a life that makes sense,” “finding something good even in bad things,” “taking the stairs without having to hold on,” “finding the strength and courage to go a step further each day,” and “managing not to waste even a moment.” One of our patients wrote: “to really find happiness, you have to lose it first.”

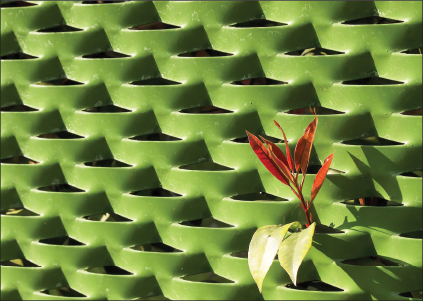

Figure 1. One of the photos taken by Matteo (treated for medulloblastoma) for his individual project on the search for happiness.

Figure 2. One of the photos taken by Lorenzo (treated for ependymoma). Lorenzo takes photographs from unusual perspectives because, as he explained, his disease has left him with a visual impairment that makes him look at reality from different angles.

More Than Meets the Eye

Sometimes a patient whose photography at first glance seemed to reflect an attempt to escape, with no obvious reference to his or her medical condition, would have a hidden, more profound meaning. For example, the photographs taken by Matteo (treated for medulloblastoma) are almost abstract. Tiny details become detached from the chaos of the background to signify absolute beauty—but always with a sense of drama (in his marked contrast of colors, distinct edges, an apparent emptying of meaning) that communicates, possibly unwittingly, a sort of anguish, a sense of isolation (Figure 1). Viola (treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia) took photographs of people smiling, but the background from which they emerge is always dark and dismal.

Lorenzo (treated for ependymoma) took pictures from unusual perspectives (Figure 2). He explained: “My photographs are the metaphor of how I try to deal with the obstacles that life places before me and how I seek happiness. I have learned how to try and overcome the obstacles from my worst limitation, the visual impairment caused by my disease. I literally had to learn to look at reality from different perspectives. Then I realized I could transform this difficulty of mine into an opportunity. I look at reality from different angles, finding particular details that make it special and fascinating. Maybe the important thing is not to see the whole picture, but to look (and live) from as many alternative and original viewpoints as possible. This enables you to give a different interpretation to what you see; it lets you find something unique in every view, with the awareness that you can find happiness in it.”

Changing Beauty

Two girls, Sefora and Martina, chose to photograph themselves and tell us explicitly about their disease, in rather startling images. Sefora (treated for synovial sarcoma) removed her wig in front of the camera, showing her bald head. She wanted not only to produce an iconographic image of cancer, but also to show how she met the challenge of the disease, looking it straight in the face. Sefora wanted to find happiness by regaining possession of her beautiful appearance, but her gesture also reveals a sense of anger and fatigue (Figure 3).

Martina (treated for Ewing sarcoma) took melancholy pictures. “I wanted my photographs to illustrate what my search for happiness has been like in this period of my life. On the one hand, there have been the signs of how my body has changed (I lost my hair, lost weight, and no longer looked the same as before, neither in appearance nor in spirit). On the other hand, there has been my refusal to succumb to these changes, my determination to find beauty, smiling faces, and freedom despite everything. It has not been easy. All of us cancer patients are trying to find happiness. Sometimes it seems like a thing beyond our reach. But thanks to the Youth Project, I’ve found an inner strength I didn’t think I had, and I’ve found it in all the other young people I’ve met here, too. I have learned to find happiness in the normal little things of every day” (Figure 4).

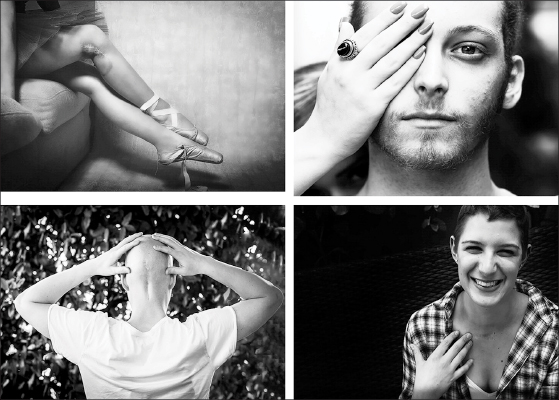

The patients also asked the professional photographers to take their pictures. Here again, the patients chose the content of the photographs. They wanted photographs of both their smiles (Figure 5) and their scars (Figure 6)—bookends in the search for happiness. The photography course culminated in an exhibition of 80 photos held in February 2017 at the prestigious Pavilion of Contemporary Art (Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea) in Milan.

Figure 3. A self-portrait by Sefora (treated for synovial sarcoma) without her wig.

Figure 4. A self-portrait by Martina (treated for Ewing sarcoma). Recording the changes in her body was a way to refuse to succumb to them, to try to find beauty and happiness despite them.

Special Experience of Engagement

Like other supportive initiatives organized over the years as part of the Youth Project, the photography project succeeded in generating enormous interest among the young participants by creating a supportive group and offering them a new way in which to express themselves and tell their stories. For the adults involved in the project (physicians, psychologists, artists, and other professionals dedicated to working with youth), it became a special experience of engagement with our young patients.

Figure 5. Photographs of the smiles of patients participating in the Youth Project (photographs by Donata Zanotti).

Figure 6. Photographs of the patients’ scars. Lorenzo (upper right) became blind in one eye; his is a scar that other people cannot see. (photographs by Veronica Garavaglia).

When the Youth Project was first launched years ago, the staff thought it would enable us to teach our patients something. Now, several years later, we have realized there is no way we can teach them how to cope with their anxieties and fears brought on by their disease. However, our patients have taught us to open our eyes, ears, and hearts and to listen to the stories they want to tell. Our patients have taught us to see our relationship with them in a different light. We are not only physicians treating patients with cancer, we are adults who have the great privilege of walking side by side with young people going through a terribly difficult time in their lives. We have learned that all these patients want is for us to be there for them. What we have to do is relatively easy—shake a hand, stay silent, try to stay light-hearted, face the burden, not give up (even when we wish we could), and believe in the power of a smile. We have to believe in the power of our projects, which give our patients the chance to see the future differently—envisioning not just the day they leave the hospital or the day they return for another round of treatment, but also, for example, the day of the photography exhibition for which they are preparing, which may be 9 months away. Nowadays, we believe we have a duty to find ways to help adolescent patients with cancer tell their stories and create beauty in a place—the hospital—that unavoidably becomes a second home to them, because where there is beauty, there is also hope. ■

References

1. Ferrari A, Clerici CA, Casanova M, et al: The Youth Project at the Istituto Nazionale Tumori in Milan. Tumori 98:399-407, 2012.

2. Magni C, Veneroni L, Silva M, et al: Model of care for adolescents and young adults with cancer: The Youth Project in Milan. Front Pediatr 4:88, 2016.

3. Ferrari A, Silva M, Veneroni L, et al: Measuring the efficacy of a project for adolescents and young adults with cancer: A study from the Milan Youth Project. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:2197-2204, 2016.

4. Ferrari A, Veneroni L, Clerici CA, et al: Clouds of oxygen: Adolescents with cancer tell their story in music. J Clin Oncol 33:218-221, 2015.

5. Ferrari A, Signoroni S, Silva M, et al: ‘Christmas Balls’: A Christmas carol by the adolescent cancer patients of the Milan Youth Project. Tumori 103:e9-e14, 2017.

6. Veneroni L, Clerici CA, Proserpio T, et al: Creating beauty: The experience of a fashion collection prepared by adolescent patients at a pediatric oncology unit. Tumori 101:626-630, 2015.

7. Clerici CA, Massimino M, Casanova M, et al: Psychological referral and consultation for adolescents and young adults with cancer treated at pediatric oncology unit. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51:105-109, 2008.

8. Proserpio T, Ferrari A, Veneroni L, et al: Spiritual aspects of care for adolescents with cancer. Tumori 100:130e-135e, 2014.

At the time this article was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, the authors were practicing at Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori and Carlo Alfredo Clerici, University of Milan, Italy.