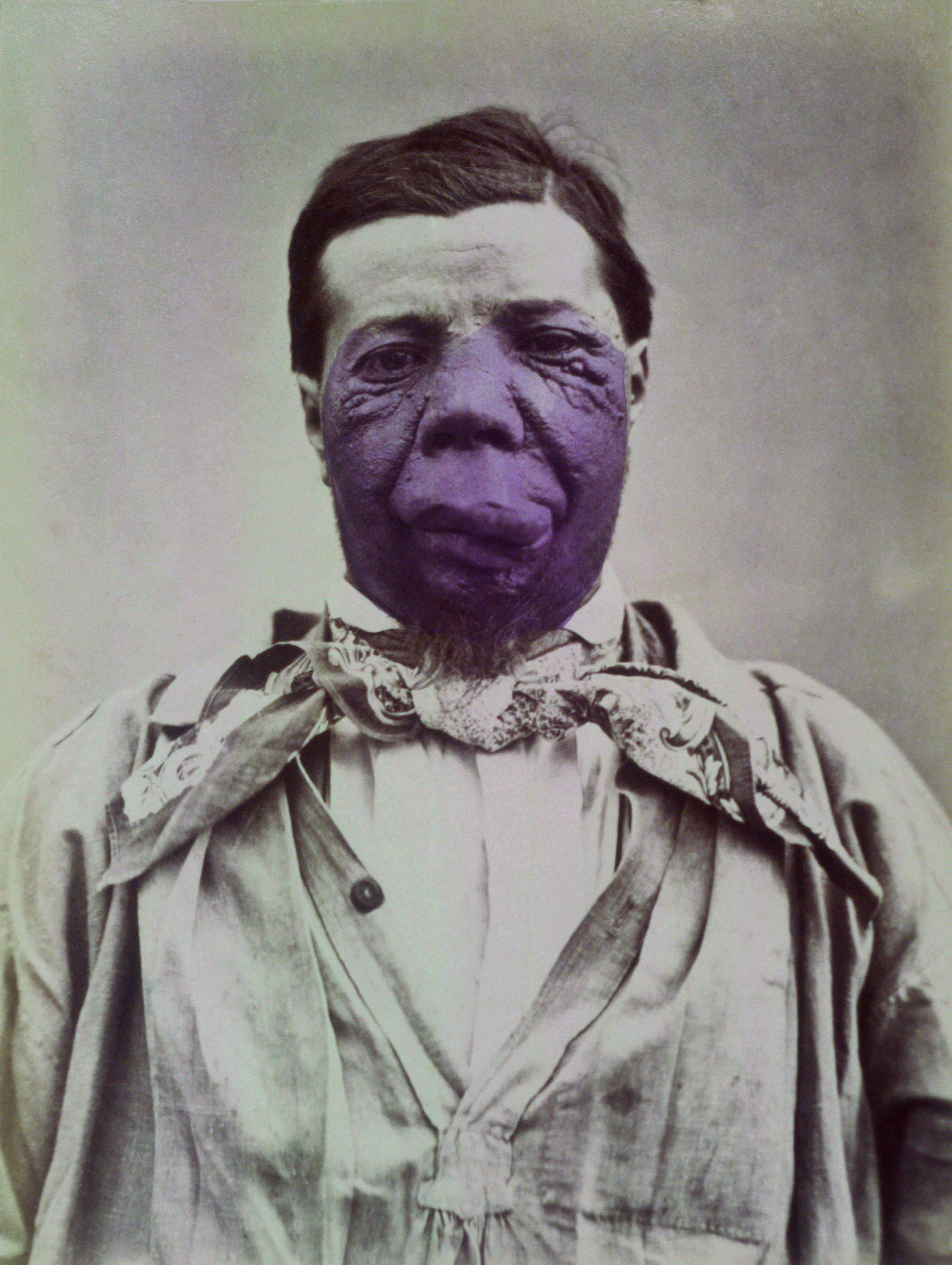

Nevus Vasculaire Albumen Print, Paris, 1869

Published in 1869, Revue Photographique des Hôpitaux de Paris was the world’s first medical journal to contain real photographs. In the seven issues produced between 1869 and 1875, 245 images were used. Dr. A. de Montméja, a Parisian ophthalmologist and leading medical photographer of this early era, edited the journal during its entire run. In 1868, he also edited a dermatology atlas, Clinique Photographique de l’Hôpital Saint-Louis, with dermatologist Dr. A. Hardy. The atlas had been introduced as a monthly series available by subscription in 1867. The idea of the subscription was not only to measure the response to the publication, but also to gain an idea of how many books could be sold.

The world’s first book with photographs was similarly introduced as a serial in 1844: William Henry Fox Talbot’s Pencil of Nature appeared in six parts between June 1844 and April 1846. Early photographic publications had original images hand pasted (tipped-in) onto special pages. Because this process was expensive, many publishers could not risk producing a photographic book without prepaid subscriptions or serialization. With the success of his serialized book, Dr. de Montméja realized not only did physicians want to see actual medical photographs along with their case histories, but that he could produce those works.

Since the mid-1840s, medical journals had reproduced medical photographs only as woodcuts or engravings; however, these secondary renditions could not render the same detail or convey the same impact as a real photograph. Original photographs allowed realistic reproduction of unusual or dramatic cases, which were important to share so physicians could see the range of the condition. Photography also expanded the scope of case presentation by the inclusion of primary images as well as other purely interesting photographs of the conditions. This photograph is an example of an image presented as an extreme of disease as well as a curiosity.

Photograph 25 in the first issue of the Revue Photographique des Hôpitaux de Paris is a case Dr. de Montméja presented as ‘noevus vasculaire,’ a type of pigmented vascular tumor. He described various types of vasculi nevi and their treatments but also noted treatment results were varied and often ineffective. Ligation of vessels, cauterization with caustic agents, and scarification by vaccination worked only in some cases. This photograph was exhibited as an example of an advanced case that should not be treated. He noted: “The lesion swelled with certain activity, and the size and position on the face precluded any successful therapy.” The lesion was hand-colored by an artist to convey a more realistic presentation of the tumor.

Natural History of Vascular Tumors

During the 1980s the nomenclature for vascular tumors was redesigned and divided into hemangiomas and vascular malformations. The natural history of hemangiomas and vascular malformations varies. Vascular malformations, such as the port-wine stain, are congenital lesions and structural abnormalities. Hemangiomas behave like neoplasms and occur most frequently on the head and neck. Some hemangiomas undergo spontaneous involution, as vessels naturally thrombose. Vascular malformations do not proliferate and grow along with normal tissue. Although some hemangiomas grow, causing extensive distortion of normal tissue, others are forms of rapidly growing sarcomas.

Vascular tumors are perhaps the most common tumors humans develop. They range from simple port-wine or other red-colored skin lesions to both large, gross lesions distorting normal anatomy and aggressive malignant neoplasms. Many congenital hemangiomas, called “strawberry birthmarks,” require no treatment when they are skin-level lesions, although at times they distort the face in remarkable ways. Vascular malformations can be associated with lesions in the brain or other parts of the body in an array of syndromes, for example, Sturge-Weber or von Hippel-Lindau disease.

Treatment Options

Treatment of vascular tumors is determined by their location and growth characteristics. Prior to modern techniques, surgical intervention was often quite an adventure, because large aberrant blood vessels caused extensive bleeding. X-ray and radium treatments offered some success, and treatment with sclerosing solutions also seemed a safe therapy. Alcohol injection, electric needle insertion, dry-ice freezing, and dozens of other inventive therapies were used and abandoned.

Today, the development of the 585-nm pulsed-dye laser has revolutionized treatment of port-wine lesions, although large vascular tumors remain a challenge for both the surgeons who excise them and the team who attempts reconstruction. Even today, surgical removal of the lesion shown in this photograph would probably not be possible. ■