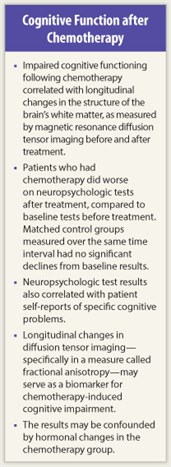

The phenomenon called “chemobrain”—impaired cognitive functioning following chemotherapy—correlates with longitudinal changes in the brain’s white matter, according a recent study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.1 Structural changes in the white matter, measured by magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging before and after treatment, correlated with the results of neuropsychologic assessments. Moreover, the objective assessments were associated with patient self-reports of cognitive problems in this small, controlled study.

Previous imaging studies have found changes in the brain following chemotherapy. But this study, unlike most others, used imaging and neuropsychologic tests before and after treatment in chemotherapy patients as well as in two control groups.

Previous imaging studies have found changes in the brain following chemotherapy. But this study, unlike most others, used imaging and neuropsychologic tests before and after treatment in chemotherapy patients as well as in two control groups.

“What is good about this study are the control groups and the fact that patient self-reports correlated with the neuropsychologic testing,” said Patricia Ganz, MD, Director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Research at the University of California, Los Angeles, Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer. Dr. Ganz, who was not involved in the study, wrote an editorial accompanying the report (see sidebar).2

First Longitudinal Evidence

The study authors, led by Sabine Deprez, MSc, of University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium, concluded that the findings “provide the first longitudinal evidence that [diffusion tensor imaging]–based assessment of the microstructural properties of [white matter] may be sufficiently sensitive to investigate the neuronal substrate of chemotherapy-induced cognitive complaints.”

The study authors, led by Sabine Deprez, MSc, of University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium, concluded that the findings “provide the first longitudinal evidence that [diffusion tensor imaging]–based assessment of the microstructural properties of [white matter] may be sufficiently sensitive to investigate the neuronal substrate of chemotherapy-induced cognitive complaints.”

Diffusion tensor imaging is a technique that allows researchers to visualize and characterize the architecture of white matter via the self-diffusion of water molecules. The investigators used a diffusion tensor imaging measure called fractional anisotropy. This parameter reflects the organization of white matter, which is important to communication among various regions of the brain; damage to the white matter can affect cognitive performance.

To determine whether fractional anisotropy values would fall after chemotherapy, the researchers compared 34 young premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer who had chemotherapy with 16 matched patients who did not have chemotherapy and 19 age-matched healthy controls. The chemotherapy patients had diffusion tensor imaging and neuropsychologic assessments before and after treatment while both control groups underwent the tests at matched intervals.

In all three groups, the baseline, prechemotherapy diffusion tensor imaging, and neuropsychologic assessments were similar. The neuropsychologic test battery measured attention, concentration, memory, executive functioning (eg, distraction), and cognitive/psychomotor processing speed. After adjusting for IQ and depression, which can be expected in cancer patients, there were no significant differences among participants at baseline.

However, 3 to 4 months after chemotherapy, diffusion tensor imaging revealed differences in the white matter among the treated patients, including significantly decreased fractional anisotropy compared to baseline. No differences were found in the two control groups.

Neuropsychologic Tests Correlate

The same pattern was reflected in the neuropsychologic test results. The chemotherapy patients performed significantly worse after treatment on attention and concentration tests, psychomotor speed, and memory. Performance on the neuropsychologic tests did not decline in the control groups over the same period.

The same pattern was reflected in the neuropsychologic test results. The chemotherapy patients performed significantly worse after treatment on attention and concentration tests, psychomotor speed, and memory. Performance on the neuropsychologic tests did not decline in the control groups over the same period.

Finally, patient-reported complaints correlated with the neuropsychologic tests. For instance, chemotherapy patients reported significantly more problems with verbal memory, and these self-reported problems with name and word finding correlated significantly with decreased performance on the controlled word association test.

The authors noted that the correlation between self-reports and neuropsychologic tests conflicts with the results of other studies. The reason for the difference, they suggested, may be the use of two time points in their study; that is, correlating changes over time in self-reports and objective test results may be more sensitive than correlating one-time scores.

Qualifying Remarks

One limitation of this study is its small size. Another, the authors pointed out, is that a majority of the patients had hormonal treatment with tamoxifen, a possible confounding factor since tamoxifen has been shown in some studies to impair cognition. There is also the possibility that early menopause due to chemotherapy influenced cognitive performance, although studies differ on the cognitive effects of menopause.

More research is needed, said the authors, on whether the white matter changes are long-term or temporary and whether the difference in cognition before and after chemotherapy is related to the degree of change in the brain's white matter. ■

Disclosure: Ms. Deprez and Dr. Ganz reported no conflicts of interest.

Expert Point of View: Controlled Study Links ‘Chemobrain’ to Longitudinal Changes in Brain

Reference

1. Deprez S, Amant F, Smeets A, et al: Longitudinal assessment of chemotherapy-induced structural changes in cerebral white matter and its correlation with impaired cognitive functioning. J Clin Oncol 30:274-281, 2012.

2. Ganz PA: “Doctor, will the treatment you are recommending cause chemobrain?” J Clin Oncol 30:229-231, 2012.

Commenting on the study by Deprez et al, Patricia Ganz, MD, noted the importance of the finding for clinicians.

Commenting on the study by Deprez et al, Patricia Ganz, MD, noted the importance of the finding for clinicians.