Syed Ali Abutalib, MD

Nicolaus Kröger, MD

Malgorzata Mikulska, MD

The ASCO Post is pleased to present the Hematology Expert Review, an occasional feature that quizzes readers on issues in hematology. In this installment, Drs. Abutalib, Kröger, and Mikulska focus on the challenges of providing cancer care amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Here they present two separate case studies—one featuring an asymptomatic immunocompromised patient with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and the other centering on an asymptomatic health-care provider—and consider the benefits and limitations of different therapeutic strategies.

Case Study 1: Asymptomatic Immunocompromised Host

A 53-year-old male patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation 8 days ago from an HLA-matched unrelated donor for high-risk AML in first complete remission. He had received a short visit from his wife on day 7. After the visit, his wife became febrile, and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS–CoV-2 was positive. Their 8-year-old son also tested positive for SARS–CoV-2.

The patient was tested routinely at the ward three times a week (this was the local protocol; institutional guidelines may vary), and the last PCR test from 2 days before was negative. A new PCR on day 10 showed positivity, but the patient was completely asymptomatic for the viral infection. The virus copy number per mL was 50,000.000, and sequencing showed the Omicron variant (routinely checked in Europe but not in the United States). The patient had received SARS–CoV-2 immunization, with a booster dose 4 weeks prior to transplantation, but without detectable -antibodies.

What would be your recommendation?

A. Provide treatment with a single dose of casirivimab/imdevimab.

B. Provide treatment with a single dose of sotrovimab.

C. Start remdesivir and steroids.

D. Start nirmatrelvir/ritonavir.

E. Provide treatment with a single dose of bamlanivimab/etesevimab.

F. Provide treatment with a single dose of tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

G. Wait until the patient becomes symptomatic to treat with a monoclonal antibody active against the Omicron variant.

Expert Perspective: It is challenging to argue that there is only one correct answer on how to manage the patient presented in this clinical vignette. Thus, we will discuss the pros and cons of the options proposed in this challenging case.

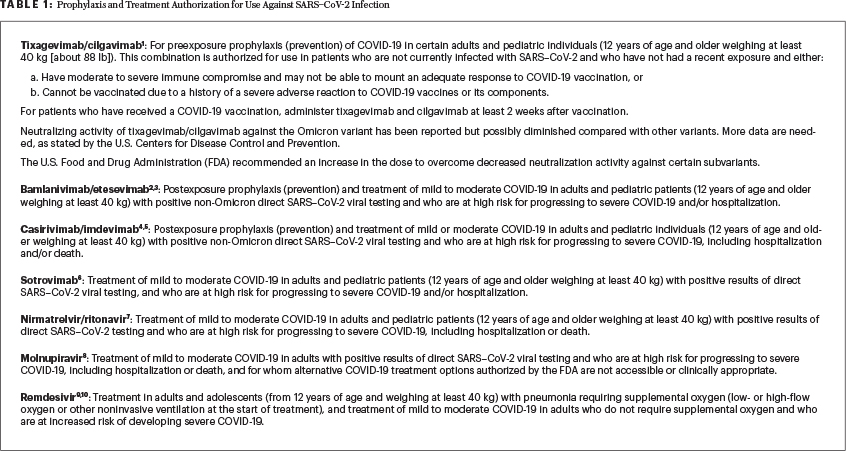

Asymptomatic PCR-positive patients such as this one were not included in the studies and hence were not contemplated in the currently available general guidelines. We have data on postexposure prophylaxis (ie, with a negative SARS–CoV-2 test), as opposed to asymptomatic PCR test positivity (our patient), and in patients with very early (~3–5 days) mild symptomatic infection (Table 11-10).

Most of us would agree that it would make sense to treat the infection as early as possible, even before the onset of symptoms, given the high risk of rapid progression to severe COVID-19 due to the underlying cancerous process and/or transplant-related severe immunosuppression. The knowledge of the comorbidities and past immunization might help us to better evaluate the risk as described in this case. Since this patient has no humoral response to primary vaccination and the booster, it is tempting to intervene with monoclonal antibodies as soon as possible. Waiting for the development of symptoms, or hoping they will never appear, might be easier in patients who responded to vaccination and received the booster dose, particularly in the case of the Omicron variant. Indeed, infection with the Omicron variant might be milder compared with that of other variants (eg, Delta), but still the risk of severe COVID-19 is present, particularly in a nonimmunized or anergic person with severe immunosuppression.

The regulatory authorities approved the antispike monoclonal antibodies, oral antivirals, and 3-day intravenous remdesivir for those with mild to moderate symptoms of COVID-19 (Table 2). For instance, in a formal request for these treatments in Italy (personal experience of one of the authors), the physician must provide the patient’s symptoms to obtain the approval. Moreover, asymptomatic subjects were not included in pivotal trials that documented the clinical benefit.

Consideration of All Choices

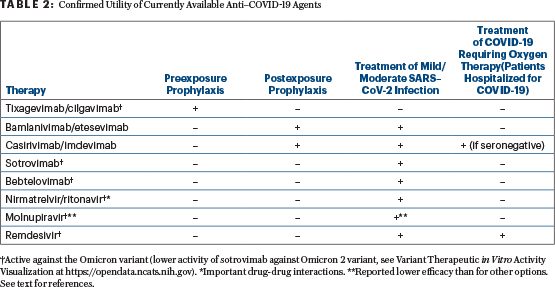

Choices A (casirivimab/imdevimab) and E (bamlanivimab/etesevimab) are incorrect because these monoclonal antibodies are ineffective against the currently dominant Omicron variant. These agents could be reasonable therapy for the non-Omicron variant in a symptomatic patient with SARS–CoV-2 infection and risk factors for severe COVID-19, or in cases of postexposure prophylaxis (ie, with a negative SARS–CoV-2 test) if most of the circulating viral variants are susceptible to these agents (Table 2).

Choice F (tixagevimab/cilgavimab) is also incorrect because this combination of long-lasting antibodies (prevention for 6 months) is approved for preexposure prophylaxis (individuals who have moderate to severe immune compromise and may not mount an adequate immune response to COVID-19 vaccination but with a negative test and without a known recent exposure). It could have been an option before transplantation when the lack of a serologic response was documented. Of note, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warns that although the Omicron variant remains susceptible to this combination, more data are needed to fully assess the activity and efficacy of this regimen in situations where the Omicron variant is circulating at high levels. Possible side effects of tixagevimab/cilgavimab include hypersensitivity reactions (including anaphylaxis), bleeding at the injection site, headache, fatigue, and cough. On February 24, 2022, following concerns about decreased neutralizing activity against certain Omicron subvariants, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended increasing the dose from 150 mg + 150 mg to 300 mg + 300 mg.

Choice C (remdesivir and steroids) is another incorrect answer because the use of steroids in an asymptomatic phase such as this, and mild to moderate infection (which does not require oxygen therapy), might increase the risk of a negative clinical outcome.

Choices B (sotrovimab in an asymptomatic immunocompromised host) and D (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir—beware of drug-drug interactions of ritonavir, which might make it unsuitable in the early posttransplant period) might protect this patient against severe COVID-19, as could also be true for 3 days of intravenous remdesivir or 5 days of oral molnupiravir (not included in the choices; of note, molnupiravir had lower efficacy in the pivotal study than the other discussed options). However, formally, SARS–CoV-2 infection with mild to moderate symptoms should be present to administer one of these agents, unlike the asymptomatic situation of our case patient.

The current evidence-based correct answer is choice G, a single dose of Omicron-active antibody (such as sotrovimab, and since February 11, 2022, in the United States also bebtelovimab [not included in the choices]) as soon as symptoms appear. However, the rationale to wait and watch for symptom development and not to treat the viral phase as early as possible is weak, especially in this patient as explained previously.

Given the tolerability of sotrovimab, the case of a severely immunocompromised patient with transplantation as a potential cure of his acute leukemia, and the high risk of early mortality from COVID-19 infection, early treatment of an asymptomatic patient should be considered and weighted against the remote possibility of the patient remaining asymptomatic with SARS–CoV-2 infection and the cost of sotrovimab. An additional motive to provide early treatment while the patient remains asymptomatic is the reduction of viral load and the length of shedding, which could reduce the risk of a nosocomial outbreak in the transplant unit or ward. Another strategy to avoid a nosocomial outbreak in the transplant unit is to transfer the patient to a COVID-19–dedicated ward within the hospital; however, attention should be paid that staff are adequately trained to provide care for highly complex patients such as transplant recipients.

In our opinion, we would treat this severely immunocompromised patient with sotrovimab (if approved by the institution) as soon as possible, while he remains asymptomatic. Otherwise, we would choose option G, as mentioned earlier.

Correct answer: G (with B being a reasonable choice in this case).

Case Study 2: Asymptomatic Health-Care Provider

10 days later…

One of your medical colleagues from the same unit or ward tests positive for SARS–CoV-2 infection. He has no symptoms of the infection. According to institutional guidelines, he has received boosters about 3 months back and has no underlying medical problems.

What would be the most reasonable next step?

A. Provided he remains asymptomatic, he should return to work after 10 days without the need for repeat COVID-19 testing.

B. Provided he remains asymptomatic, he should return to work after 5 days without the need for repeat COVID-19 testing.

C. If he develops mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms, he should be treated with a monoclonal antibody that is active against the Omicron variant.

D. COVID-19 testing should be increased among asymptomatic medical staff.

E. Postexposure prophylaxis should be provided to all admitted hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.

F. Provided he remains asymptomatic, he should return to work after 10 days with a negative PCR or rapid antigen test.

Expert Perspective: When deciding on criteria for ending home isolation of COVID-19 cases, health authorities recommend considering factors such as the existing capacity of the health-care system, laboratory diagnostic resources, and the current epidemiologic situation. Both the U.S. CDC11 and the European CDC12 guidelines address specifically the requirements of returning to work for health-care professionals working with a vulnerable population and in case of no staff shortage. Here we describe their recommendations for this case.

U.S. CDC: Fully vaccinated health-care providers who remained asymptomatic throughout their SARS–CoV-2 infection and are not moderately to severely immunocompromised can return to the medical environment if at least 7 days have passed since the date of their first positive viral test and they with a negative rapid antigen or PCR test obtained within 48 hours prior to returning to work or 10 days since the date of their first positive viral test if testing is not performed or they have a positive test at days 5 to 7. Of note, this CDC recommendation is often confused or inadvertently misreported with another CDC recommendation, which is focused on the general population (and not for health-care providers returning to a vulnerable patient population that is asymptomatic with SARS–CoV-2).11

European CDC: Fully vaccinated health-care providers working with a vulnerable patient population can return to work after 10 days of isolation and a single negative test, or 2 consecutive negative SARS–CoV-2 reverse transcriptase–PCR tests in 24-hour intervals in case of returning prior to 10 days.12

Consideration of All Choices

Choice A is the correct answer according to the U.S. CDC but an incorrect answer according to the European CDC guidelines.

Choice B would have been correct according to the U.S. CDC if the person was not a health-care provider taking care of a vulnerable patient population. In the current scenario, this is an incorrect answer.

Choice C is incorrect. Given that the medical colleague has no comorbidities, antiviral or monoclonal treatments are unnecessary even if he develops mild to moderate symptoms.

In the case of choice D, the increase in testing could be useful if treatment of asymptomatic otherwise healthy persons was being contemplated, but such is not the case. However, it is prudent to adopt enhanced precautions (eg, FPP2 masks, gowns) for all hospital staff (regardless of the exposure status) while they remain in the hospital areas including during coffee and meal breaks.

Choice E is incorrect because postexposure prophylaxis with both casirivimab/imdevimab and bamlanivimab/etesevimab is ineffective against the Omicron variant.

Choice F is correct according to the European CDC but incorrect according to the U.S. CDC. Both the U.S. CDC11 and the European CDC12 recommend that if isolation is finished before day 10 (eg, due to staffing issues), they should continue to properly wear a well-fitted mask around others at home and in public for 5 additional days (days 6–10) after the 5-day isolation period.

Correct Answers: A according to the U.S. CDC and F according to the European CDC. Further variability in answers may exist based on geographic guidelines and institutional preferences.11-13 The latter also equates health-care staff shortage and may allow early termination of isolation especially in asymptomatic health-care provider(s).

The first case was adapted from a case posted on the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) website at ebmt.org.

DISCLOSURE: Dr Abutalib has served on the advisory board for AstraZeneca. Dr Kröger and Dr. Mikulska reported no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Tixagevimab and cilgavimab (Evusheld) for pre-exposure prophylaxis of COVID-19. JAMA 327:384-385, 2022.

2. Cohen MS, Nirula A, Mulligan MJ, et al: Effect of bamlanivimab vs placebo on incidence of COVID-19 among residents and staff of skilled nursing and assisted living facilities: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 326:46-55, 2021.

3. Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, et al; BLAZE-1 Investigators: Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab in mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med 385:1382-1392, 2021.

4. O’Brien MP, Forleo-Neto E, Musser BJ, et al: Subcutaneous REGEN-COV antibody combination to prevent Covid-19. N Engl J Med 385:1184-1195, 2021.

5. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al: REGEN-COV antibody combination and outcomes in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 385:e81, 2021.

6. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al; COMET-ICE Investigators: Early treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med 385:1941-1950, 2021.

7. McDonald EG, Lee TC: Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for COVID-19. CMAJ 194:E218, 2022.

8. Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al: Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 386:509-520, 2022.

9. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al: ACTT-1 Study Group Members: Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19: Final report. N Engl J Med 383:1813-1826, 2020.

10. Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, et al: Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe Covid-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med 386:305-315, 2022.

11. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Guidance on Ending the Isolation Period for People with COVID-19, Third Update. Available at https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Guidance-for-discharge-and-ending-of-isolation-of-people-with-COVID-19-third-update.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2022.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Ending Isolation and Precautions for People With COVID-19: Interim Guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html. Accessed on March 10, 2022.

13. European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia: COVID-19 in Hematology-Oncology Patients. Available at https://ecil-leukaemia.com/en/resources/resources-ecil. Accessed on March 10, 2022.

Dr. Abulatib is Co-Director, Hematology and Cellular Therapy Programs; Director, Clinical NMDP and CTCA Apheresis Programs, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, an Affiliate of City of Hope, Zion, Illinois; Associate Professor, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. Dr. Kröger is Professor of the Department of Stem Cell Transplantation at the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany, University Hospital Hamburg, Germany; President of the European Bone Marrow Transplantation Society (EBMT). Dr. Mikulska is Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases, Division of Infectious Diseases, Ospedale Policlinico San Martino and University of Genova, Italy; Former Secretary, Infectious Diseases Working Party, EBMT.