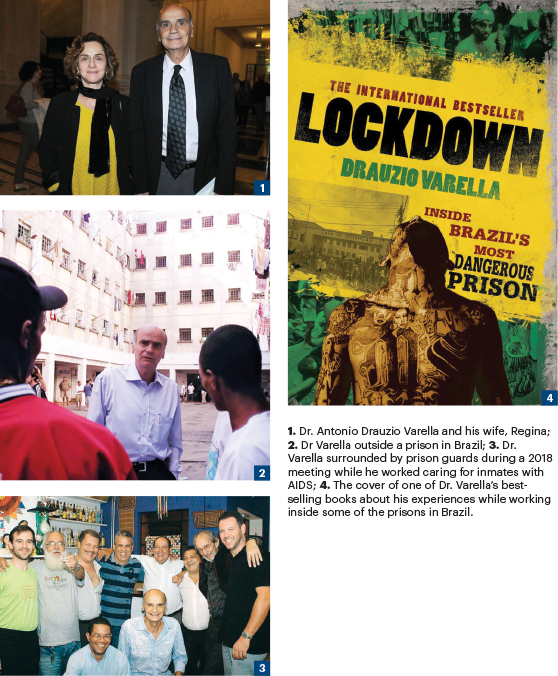

In this edition of Living a Full Life, Guest Editor Jame Abraham, MD, spoke with Antônio Drauzio Varella, MD, a Brazilian oncologist, educator, scientist, and medical science popularizer in the press and television, as well as a best-selling author.

Guest Editor

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP

Jame Abraham, MD, FACP, is Acting Chair of the Taussig Cancer Institute and Chair of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Cleveland Clinic. He is also Professor of Medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine.

Antônio Drauzio Varella, MD, was born in 1943 in São Paulo, Brazil. “My father was from Spain, but his family relocated to São Paulo when he was just 2 years old. My mother’s family came here from Portugal. I grew up in a poorer section of the city. As a kid, I played soccer in the streets all day long until it was too dark to see the ball. Once the boys in the neighborhood reached 14, they went to work in one of the factories. I was the only one of my gang of street kids who had the opportunity to go to the university,” he shared.

Dr. Varella continued: “My father always insisted that his children would get a good education. I was one of four children, and my mother died when I was four. So, my father took us to live with my grandmother, but she died a few years later, leaving my father alone with us to raise. He was a strong man and persevered, making sure I always studied, urging me forward so I wouldn’t have such a hard life like his. When he asked what I wanted to be, I said a doctor. And I never doubted or regretted that desire, to this day.”

Public Health Calls

Dr. Varella entered the University of São Paulo when he was 18. “I finished medical school in 1967, more than 50 years ago. And then I decided to do my residency in public health. I spent 2 or 3 years in public health until I received an invitation to work in infectious disease with a professor from another public hospital in São Paulo. It was during that time I started studying immunology, which I rapidly became interested in; I was eventually invited to present a lecture at the Cancer Hospital of São Paulo about the emerging potential of immunology in oncology,” said Dr. Varella. “But I wasn’t totally prepared for such an undertaking, so I asked to be able to treat patients with malignant melanoma with BCG [bacillus Calmette-Guérin], and that’s what I did, every week.”

Antônio Drauzio Varella, MD

- On the early use of oral BCG in malignant melanoma: “It was one of the first scientific demonstrations of a well-studied case, including images, showing it was possible to stimulate the immune system and provoke tumor rejection at a distance.”

- On being invited to do radio interviews on the AIDS epidemic: “This was important public health messaging, and I was glad to have the opportunity to do it.”

- On starting a medical education YouTube channel: “It is extremely satisfying, because disseminating knowledge about health issues fundamentally changes public attitudes and behavior about human health.”

Dr. Varella explained that at the time, BCG was given intradermally because of the difficulty in transporting the temperature-sensitive vaccine. But Brazil and Canada still had oral BCG, which was known to be effective in tuberculosis prevention. “I had one patient whose malignant melanoma in the forearm had recurred and was present in several nodes. At that time, surgery was the only weapon against malignant melanoma, so they proposed to amputate his arm. He declined surgery and returned a month later, with metastatic melanoma. Given the lack of options at the time, I decided to give him oral BCG; within a few weeks, the nodes became hot and red and began to regress until they disappeared completely,” he related.

Dr. Varella described the eventual study of 30 patients with unresectable disseminated melanoma who were treated with oral BCG, with weekly doses ranging between 200 mg and 28,000 mg. Five patients died in the first 2 months of treatment. Of the remaining 25 patients, 2 had complete regression, and 1 had partial regression.

“We published a paper in the journal Cancer in 1981, which was the first Brazilian research in the magazine,” explained Dr. Varella. “I presented these results twice at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. It was one of the first scientific demonstrations of a well-studied case, including images, showing it was possible to stimulate the immune system and provoke tumor rejection at a distance. That is how I became an oncologist.”

At the Beginning of the AIDS Epidemic

In 1983, during a 3-month visit to Sloan Kettering Memorial Hospital, Dr. Varella realized that AIDS would hit hard in Brazil. Although he already had more than 10 years of experience in oncology, the HIV-positive patients he saw in the United States made an impression on him.

Dr. Varella continued: “These patients were all young people, many of them artists and intellectuals. I had the feeling that a major tragedy was about to happen. There was a researcher at MSK, Dr. Susan Krown, who was working with interferon in Kaposi sarcoma. I started studying day and night and when I returned to Brazil, I was the only oncologist who had experience with disseminated Kaposi sarcoma. I began to treat the first cases. Infectious disease specialists had little experience with it. I treated people from all over Brazil at the Hospital do Câncer,” he said.

Dr. Varella stressed there was an antihomosexual sentiment in Brazil at the time, which extended across socioeconomic classes. “There was not only systemic prejudice, but also a huge amount of misinformation about AIDS, which also diminished our ability to confront it as a public health crisis,” said Dr. Varella.

A New Career in Public Broadcasting

Dr. Varella knew that dissemination of accurate knowledge was a vital step in battling the emerging AIDS epidemic, and he was fortunate when his friend, Fernando Vieira de Mello, Director of Jovem Pan radio, invited him to do an interview about AIDS. “I resisted at first, because in my view a doctor who spoke on mass media was viewed negatively by his colleagues. But I will never forget what Fernando said: ‘Do you want to be on good terms with your colleagues or get this information out to the people?’ That question swayed me.”

“I returned to the station after a few days, and Fernando explained that the messages must be short and directed to the group we were trying to reach. So, I began the broadcast by saying: ‘I am Dr. Drauzio Varella, talking to those of you who are young, homosexual, and taking intravenous drugs.’ This was important public health messaging, and I was glad to have the opportunity to do it,” he noted.

Popular Response Fuels More Projects

Because of the popular response of his radio broadcasts, Dr. Varella was asked to make a video about AIDS. “We filmed the video with a professional producer who shot it in the prison, which had about 7,500 inmates. In Brazil, we have conjugal visitation, and no precaution was taken to help those women, to inform them of the risks (of contracting HIV). In the infirmary, there were people dying of cachexia. It was a tragedy that left a deep impression on me. After a few weeks, I went to the head of the medical department of the São Paulo penitentiary system and offered to do volunteer work. My thinking was that we first need to demonstrate what’s happening here, how many people in here are infected; then, based on that number, we can define what should be done,” he explained.

Dr. Varella continued: “I proposed to conduct a survey with the people who received conjugal visits. It was a significant sample; there were 1,500 people enrolled in the program. I got a donation of test kits, and the collection work could be done by the users in the prison, those who knew how to find a vein better than anyone. I spoke with the director, and he brought me five prisoners. I asked, and they had experience. ‘We can get a vein with a crooked needle, with this equipment of yours, it’s child’s play,’ one of them replied.”

“The future of cancer research and treatment is very bright, and there is no better time to be a part of this incredible medical journey than now.”— Antônio Drauzio Varella, MD

Tweet this quote

Blood was collected from 1,492 people. “We sent the samples to Dr. Ronald Bukowski, a dear friend, who tested them in the laboratories of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. HIV prevalence was 17.3%,” Dr. Varella stated. “I started using these data to talk to the authorities. At a minimum, we needed to distribute condoms for the conjugal visits and alert the women and send them to health clinics. No one wanted to hear about it. This paper was published, but it took a long time, 2 or 3 years for the authorities of the prison system to agree with my suggestions for preventive medicine.”

Multiple Projects, but the Clinic Always Came First

Dr. Varella writes columns about popular science and medicine for several large Brazilian newspapers and is also involved in a series of programs on TV Globo, a Brazilian television network dedicated to various medical and public health issues. Dr. Varella is also a published author, having penned 18 books, including his best-selling memoir Estação Carandiru, which chronicles his experiences in the Carandiru Penitentiary, during which a famous prison riot occurred, leaving 111 inmates dead. Since 1989, he has been seeing patients once a week as a voluntary doctor in several prisons of São Paulo.

Dr. Varella stressed that although he pursued numerous projects, his career was largely spent in the clinic, caring for patients with cancer. “After 2010, I began to reevaluate my career, as I was getting older and knew long days in the clinic would soon come to an end. So, I decided to devote more of my energies toward education, which I find very rewarding. Given that fewer and fewer young people watch TV, we started a medical education YouTube channel, which has millions of viewers. It is extremely satisfying, because disseminating knowledge about health issues fundamentally changes public attitudes and behavior about human health,” he shared.

Asked for a final thought for the readers of The ASCO Post, Dr. Varella responded: “There is medical magic in the oncology profession, because our work with our patients is done in the shadow of death, and the doctor resides in the imagination of the anxious patient. It is the duty of the oncologist to present a calming and confident presence to the patient with cancer. That’s our responsibility, and it’s not easy to be available all the time for our most needy patients. It takes a special dedication to enter this field, and it is important to know that before making the commitment. But the rewards are like no other in medicine. The future of cancer research and treatment is very bright, and there is no better time to be a part of this incredible medical journey than now.”

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Varella reported no conflicts of interest.