An abstract presented at the 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting titled “Evaluating Unconscious Bias During Speaker Introductions at an International Oncology Conference,” by Narjust Duma, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Thoracic Oncologist at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center in Madison, and her colleagues1 was so impactful that it led ASCO to develop The Language of Respect guidance2. The document aims to rectify findings from the study showing how unconscious bias is reflected in and reinforced through the use of gender-subordinating language during speakers’ introductions at the ASCO Annual Meeting and other ASCO symposia.

Narjust Duma, MD

In the study, Dr. Duma and her colleagues reviewed 812 videos of archived speaker introductions at the 2017 and 2018 ASCO Annual Meetings to examine how professional titles were used during the introductions. Among the presenters, 530 were non-Hispanic white; 743 held a medical degree or a medical degree and a doctorate; and 484 held an associate or full professorship. The study found that female speakers were less likely to be addressed by their professional title compared with male speakers, 62% vs 81%, respectively, and were more likely to be addressed by their first name alone, 17% vs 3%, respectively. In addition, male introducers were more likely to address female speakers by first name alone compared with female introducers, 24% vs 7%, respectively. However, there were no gender differences in the rate of professional address when women were making the introductions. The study also found that black speakers of either gender were less likely to be addressed by their professional title when compared with their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

Ensuring Mutual Respect

Tatiana M. Prowell, MD

“Dr. Duma’s study showed there are considerable differences in the likelihood of receiving a respectful, professional form of address during speaker introductions based on the gender of the speaker,” said Tatiana M. Prowell, MD, Chair of ASCO’s Annual Meeting Cancer Education Committee, coauthor of The Language of Respect document, and Associate Professor of Oncology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Breast Cancer Scientific Liaison in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Office of Oncologic Diseases. “We felt there was a simple approach to remedy inconsistency in speaker introductions and that is to be explicit about our expectations and instructions. In The Language of Respect document, we make it clear to our session moderators that everyone is to be introduced in a professional fashion.”

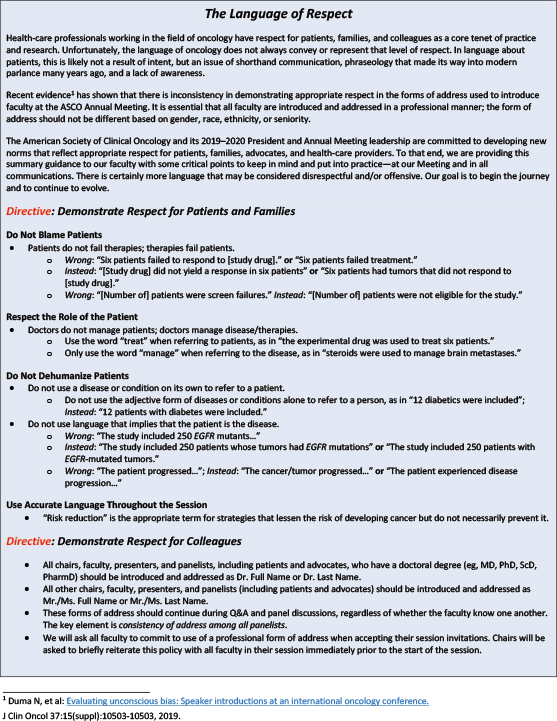

For example, all chairs, faculty, presenters, and panelists, including patients and patient advocates, who have a doctoral degree should be introduced and addressed as Dr. and full name or Dr. and last name. Speakers without a doctoral degree are to be addressed as Mr. or Ms., followed by their full name. The Language of Respect document has been included in ASCO’s Faculty Presentation Guidelines for the Annual Meeting and for all ASCO symposia and may be downloaded at https://meetings.asco.org/am/faculty-instructions.

Respect for Patients, Too

Furthermore, The Language of Respect document includes directives for demonstrating respect for both patients and their family members, as well as professional colleagues. For example, the document stresses avoiding the use of terms that appear to blame patients when their cancer progresses, such as, “Six patients failed treatment.” Instead say, “Six patients had tumors that did not respond to the study drug.”

The document also warns against dehumanizing patients by referring to them as their diseases. For example, “The study included 250 EGFR mutants.” Rather, authors should use language such as, “The study included 250 patients whose tumors had EGFR mutations.”

In an interview with The ASCO Post, Dr. Prowell discussed how The Language of Respect guidance can help address unconscious bias in oncology, demonstrate greater respect for patients and colleagues, and eliminate the use of dehumanizing language in clinical trials.

Reducing Microaggressions Against Minority Physicians

How might ASCO’s The Language of Respect guidance prevent or reduce microaggressions against female and minority physicians during ASCO presentations?

The data from Dr. Duma’s study on evaluating unconscious bias presented at the 2019 ASCO Annual Meeting showed that women were much more likely than men to be introduced informally, including by first name alone. This issue was compounded for physicians of color.

We know there are fewer women and fewer physicians of color in senior roles, which means they are less frequently going to be lead authors of studies, full professors, department chairs, or directors of cancer centers. So, how they are introduced at meetings really matters. A professional introduction signals the speaker merits the audience’s attention.

“In The Language of Respect document, we make it clear to our session moderators that everyone is to be introduced in a professional fashion.”— Tatiana M. Prowell, MD

Tweet this quote

If a woman or a physician of color is introduced by first name alone, for example, the audience could reasonably not even know the person is a doctor. Add in the fact that a woman or person of color may be less well known to the audience because of implicit bias, perhaps due to everything that comes downstream from that bias, including a slower path to promotion, and less funding for research. Then it’s not difficult to see how something as seemingly minor as the way a speaker is introduced can reinforce an unconscious bias.

It is my goal to have all speakers addressed respectfully—not just during the introduction of their presentations, but throughout the question-and-answer period as well. Having this protocol in place will, of course, not eliminate unconscious bias at the podium, but it will raise awareness of it. That is already happening. Since the attention Dr. Duma’s presentation generated, I have heard multiple stories of men introducing women informally and then spontaneously stopping and correcting themselves. Sometimes, it is that simple. It’s just a matter of calling our collective attention to it.

When we developed The Language of Respect guidelines for the 2020 ASCO Annual Meeting, I did not expect it to have an impact beyond the Annual Meeting. I’ve been pleasantly surprised to hear from physicians involved with a number of different organizations, including the American Society of Hematology and the American College of Physicians, who have proposed adapting The Language of Respect document for their own organizations.

I don’t think anyone envisioned how much of a catalyst for change this study, and the resulting guidelines, could be over a relatively short period. It’s gratifying to see the medical community embrace the need for a more inclusive culture. Physicians are, of course, no strangers to the idea of continuing education and changing practice in response to studies. That instinct for continual self-improvement is on full display in the response of most of our colleagues—both women and men—to seeing the data from Dr. Duma and her colleagues.

Conveying Respect for Patients

How can the guidance improve respectfulness shown to patients and their family members?

The other piece of The Language of Respect document is about demonstrating respect in how we address patients and refer to them, which has become even more important with social media, an increasing patient presence at medical conferences, and routine patient access to clinic notes. What I was hearing from patient advocates is that the shorthand language we’ve been taught in medical school to describe a patient’s medical condition is sometimes hurtful to patients. For example, referring to patients as their disease is understandably offensive to a lot of people.

“A professional introduction signals the speaker merits the audience’s attention.”— Tatiana M. Prowell, MD

Tweet this quote

To be clear, I don’t think there is any ill intent behind referring to patients this way—I think this shorthand developed as a mechanism to streamline communication between medical professionals—but nonetheless, it is disrespectful to patients, and in 2020, it feels outdated. That language is an artifact from a time when patients were not viewed as partners in their care or in drug development. We’re in a different era now.

So, this document is a way to ensure that we are communicating respect for everyone in the oncology community: our patients and our medical colleagues.

Using Precise Language in Clinical Trial Results

Please talk about how using imprecise language when describing clinical trial results can result in dehumanizing patients.

There was a time when patients were not in the room listening to our conversations at scientific conferences, and not reading our

clinic notes or medical journals, and many researchers had never met a single patient advocate. In 2020, we have Twitter and other social media platforms, which have greatly improved patient access to scientific information as well as to scientists and clinicians. We have patient advocates attending conferences in increasing numbers, including some who are submitting abstracts and serving as speakers in sessions, as the experts in their lived experience with a disease. Now that we know patients are potentially always listening to our conversations, we have an obligation to be more mindful of the language we use in clinic notes and in descriptions of participants in clinical trials, both for clarity and for respect.

Whenever I hear or see study results that refer to patients by their gene mutations, for example, “The study included 25 BRCA mutants,” I cringe. Patients should never be referred to as mutants, period.

What does it mean to say that the study included BRCA mutants? I can’t even be sure as a listener or reader. In addition to being demeaning, the language is also imprecise, because it does not make clear whether participants had germline mutations or the tumors had somatic mutations, or both. So, in that example, it’s not only disrespectful, it is also poor communication because it fails to clearly define the patient population.

At the end of the day, the most compelling reason to change the way we speak is that we are not treating mutations or tumors, we are treating people who happen to have a disease. I believe that having our language serve as a reminder of that is meaningful and keeps us human.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Prowell reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Duma has served as a consultant or advisor to Inivata and AstraZeneca.

REFERENCES

1. Duma N, Durani U, Woods CB, et al: Evaluating unconscious bias: Speaker introductions at an international oncology conference. J Clin Oncol 37:3538-3545, 2019.

2. ASCO Annual Meeting. Faculty instructions: Demonstrating respect for colleagues and the language of respect. Available at https://meetings.asco.org/am/faculty-instructions.

Accessed March 19, 2020.