Bookmark

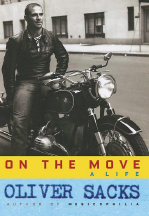

Title: On the Move: A Life

Author: Oliver Sacks, MD

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

Publication date: April 28, 2015

Price: $27.95, hardcover; 416 pages

Our ability to detect cancer has grown markedly over the past several decades, with the advent of more sensitive screening methods, new biomarkers, and advanced imaging tools. The unraveling of the human genome will further increase the detection, treatment, and prevention processes, leading to better outcomes for patients. Although cancer cells are microscopic, their greatly magnified malignant forms become visible to the human eye on a stained slide. Not so with many of the maladies that hide deep inside the human brain. Therefore, neurologists must also be detectives, creating inventive ways to diagnose and treat their patients.

One such neurologic detective is British expat Oliver Sacks, MD, best known for his collections of neurologic case histories, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, and An Anthropologist on Mars. Awakenings, his book about a group of patients who had survived the great encephalitis lethargica epidemic of the early 20th century, inspired the 1990 Academy Award–nominated feature film starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

A Compelling Writer

Dr. Sacks recently added a new book to his impressive oeuvre, On The Move: A Life, which begins with this arresting sentence: “When I was at boarding school, sent away during the war as a little boy, I had a sense of imprisonment and powerlessness, and I longed for movement and power, ease of movement, and superhuman powers.” Besides being a provocative and absorbing physician, Dr. Sacks is a compelling writer.

Unfortunately, On the Move was destined to be his final book. In a February 2015 op-ed piece in The New York Times, he announced that widespread metastases from an ocular tumor had been discovered. Measuring his anticipated remaining time in months, he expressed his intent to “live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can.” He added: “I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.”

Sadly, Dr. Sacks passed away on August 30, 2015.

Dr. Sacks—“the poet laureate of medicine”—has capped his illustrious career with a fine book that peels off the white coat and bares the man behind the MD, with the same unbridled honesty and humor seen in the memoir Megalies, by well-known oncologist Lodovico Balducci, MD. Dr. Sacks’ candor erupts early in the book with a discussion of his sex life, which was psychologically demolished when he was 18 years old by his mother’s dramatic reaction to his homosexuality: “You are an abomination. I wish you were never born.”

Dr. Sacks reminds the reader that his mother, one of the first female surgeons in England “and so open and supportive in many ways,” was a product of the times and her orthodox Jewish upbringing. Moreover, in Britain in the 1950s, not only was homosexuality frowned upon, but it was also a criminal offense punishable by prison. He ends that distressing section noting that his mother’s words haunted him throughout his life.

Before and After Neurology

Those who know of Dr. Sacks through his best-selling books on the oddities of his neurologic work will be pleasantly surprised to read about his life as a drug-loving motorcycle aficionado and Muscle Beach powerlifter. He writes, “I indulged in staggering bouts of pharmacologic experimentation, underwent a fierce regimen of bodybuilding at Muscle Beach (for a time I held a California record, after I performed a full squat with 600 pounds across my shoulders), and racked up more than 100,000 leather-clad miles on my motorcycle. And then one day I gave it all up—the drugs, the sex, the motorcycles, the bodybuilding.”

When Dr. Sacks began practicing as a neurologist, the theoretical understanding of the relationship of the brain to the conscious mind was still based on gross anatomy: If a portion of the brain was damaged, we might be able to discover by observation of the patient what its function was. Advances in brain imaging have informed new conceptions of the brain as a highly plastic environment in which there is constant reorganization. However, in the early 1990s, Dr. Sacks became acquainted with Gerald Edelman, MD, and his telling of that eventful philosophy-shaping relationship is done with spunk and humor.

Dr. Edelman’s theory of neural Darwinism, by which individual consciousness is explained as the function of a process of natural selection between cohorts of competing nerve cells, greatly influenced Dr. Sacks’ career. He described Dr. Edelman’s theory as the “first truly global theory of mind and consciousness.”

There was, of course, a certain amount of professional combativeness. Dr. Sacks writes that Dr. Edelman once said to him, “You’re no theoretician.” To which Dr. Sacks replied, “I know, but I’m a field-worker, and you need the sort of fieldwork I do for the sort of theory-making you do.” Dr. Edelman agreed, and they settled it over a cold beer.

Uplifting Life Story

Dr. Sacks’ life story is fascinating and uplifting on many levels, and reading about him rarely disappoints. He has suffered from lifelong, crippling shyness—hard to imagine when his bigger-than-life personality is on display page after page. More comfortable in water than on land, he has been a lifelong swimmer and scuba diver.

He has also waged a lifelong battle against prosopagnosia, known popularly as “face blindness,” a condition that does not allow his brain to keep a record of people’s faces. As a result, everyone becomes a stranger after the first meeting unless certain prompts are used. The section on the clinical and social challenges of this condition is riveting as well as humorous.

Most people were first introduced to Dr. Sacks in the movie Awakenings. Although a good movie, it does not open the clinical window into the neurologic challenges that Dr. Sacks puzzled out daily in his postencephalitic patients. Of that experience he writes:

What fascinated me was the spectacle of a disease that was never the same in two persons.… When I wandered among my postencephalitic patients, I sometimes felt like a naturalist in a tropical jungle, sometimes, indeed, in an ancient jungle, witnessing prehistoric, pre-human behaviors—grooming, clawing, lapping, sucking, panting, and a whole repertoire of strange respiratory and phonatory behaviors.

This is the kind of medical intrigue and writing that have made Dr. Sacks famous, and On the Move is one big roiling celebration of writing, science, and a life lived to its fullest.

Powerful Ending

The closing chapter, “Home,” is where the otherwise robust doctor confronts the disease that readers of The ASCO Post engage daily: cancer. “As I entered my seventies, I was in excellent health; I had a few orthopedic problems but nothing serious or life-threatening.… In December of 2005, however, cancer made its presence, suddenly and dramatically known.…”

Closing a book with a powerful ending is very difficult, even for the most accomplished writer. Dr. Sacks closes his final book in a way that will leave his readers wanting more. But everything comes to an end. On the Move has a few missteps, mainly when the author toggles time periods—tough to do and maintain a fluid narrative—but that small gripe aside, Dr. Sacks’ book is highly recommended. ■