A session at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium focused on the special needs of cancer caregivers. In a large survey, caregivers of persons with cancer reported higher levels of stress and significantly more duties than caregivers of other patients. But, according to research from Massachusetts General Hospital, early palliative care interventions may offer benefits to these caregivers.

Cancer Caregivers: A Higher Stress Burden

In an analysis of data from 1,275 caregivers in the United States, persons caring for patients with cancer reported a higher burden and significantly more hours per week of caregiving, as compared with individuals who care for people with other conditions.1 The analysis, which came from the National Alliance for Caregiving, sheds light on the state of cancer caregiving in the United States.

Caregiving can be extremely stressful and demanding—physically, emotionally, and financially. The data show we need to do a better job of supporting these individuals, as their well-being is essential to the patient’s quality of life and outcomes.— Erin Kent, PhD, MS

Tweet this quote

“Our research demonstrates the ripple effect that cancer has on families and patient support systems,” said Erin Kent, PhD, MS, of the Outcomes Research Branch of the Healthcare Delivery Research Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). “Caregiving can be extremely stressful and demanding—physically, emotionally, and financially. The data show we need to do a better job of supporting these individuals, as their well-being is essential to the patient’s quality of life and outcomes.”

Data from the 2015 Caregiving in the United States study showed cancer caregivers were “more likely to be in what we call ‘high-burden-of-care’ situations,” Dr. Kent revealed. Among the significant findings (all P < .05) compared with caregivers of other patients were that cancer caregivers:

- Reported feeling a “high burden” (62% vs 38%);

- Reported being highly emotionally stressed (50% vs 37%);

- Spent nearly 50% more hours per week providing care, although they were caregivers for a shorter overall duration (1.9 years vs 4.1 years);

- Provided more assistance with activities of daily living in every category;

- Were more likely to perform medical and nursing tasks (71% vs 55%);

- Were more likely to communicate with health-care professionals and to advocate on behalf of the patient;

- Were twice as likely to report needing more help and information with making end-of-life decisions (40% vs 21%).

Dr. Kent summarized these findings: “Cancer caregiving typically lasts for a shorter time period but is more intense in terms of the number of hours and tasks, in particular activities of daily living. Cancer caregivers are more likely to help with communicating with providers, monitoring health conditions, advocating with providers and agencies, and wanting help with end-of-life decision-making, and they report higher burden and emotional stress, some of which is related to helping with key activities.”

Benefit of Early Palliative Care on Caregivers

Areej El-Jawahri, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, described a study among family caregivers of patients with non-colorectal gastrointestinal and lung cancers.2 Harry VanDusen reported results of a similar program for caregivers of recipients of a hematopoietic stem cell transplant.3

This is the first study showing the positive impact of a patient-focused palliative care intervention on family caregivers. But we do need larger studies with a robust family caregiver sample size to fully assess the effect.— Areej El-Jawahri, MD

Tweet this quote

Dr. El-Jawahri’s trial included 275 newly diagnosed patients and their family caregivers, who were randomized to receive a palliative care intervention or standard oncology care. The mean age of the family caregivers was 57 years, and most of them were women. The intervention included at least two meetings a month with a palliative care physician (including in-patient palliative care if the patient was hospitalized). The control subjects saw palliative care physicians only upon request by the patient, caregiver, or clinician.

Discussions between palliative care clinicians and patients/caregivers were primarily related to symptom management (74.7%), coping (70.2%), establishing a rapport (44.4%), and understanding of the illness (38.4%). Caregivers were present for 2,049 of the 2,862 visits (71.6%).

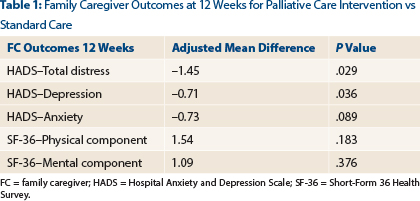

The researchers evaluated the effect of the intervention at weeks 12 and 24 on caregivers in terms of depression and anxiety symptoms according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), overall psychological distress by the total HADS score, and quality of life by the Short-Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36). They found that the intervention had a significant effect on total distress and depression but not on quality of life or anxiety (Table 1). At 12 weeks, the researchers did observe improvement in some aspects of quality of life, including vitality (P = .050) and social functioning (P = .048), but at 24 weeks, they saw no difference in subdomains.

At 24 weeks, in an analysis that did not account for missing data, the intervention showed no significant effect on any measure. However, in an analysis of the intervention 3 months before the patient’s death, which accounted for missing data, significant effects were observed on total distress, depression, and anxiety; the mean difference in these scores was 6.09 (P = .002), 3.10 (P < .001), and 0.94 (P = .049), respectively. Again, no differences were observed in quality of life.

“This is the first study showing the positive impact of a patient-focused palliative care intervention on family caregivers,” Dr. El-Jawahri said. “Of note, a lot of the family caregiver-directed interventions in the context of oncology have only yielded marginal benefits at best when it comes to psychological distress and no effect on quality of life. This is why this study is noteworthy, but we do need larger studies with a robust family caregiver sample size to fully assess the effect.”

Our study is the first to show a positive impact of a patient-focused palliative care intervention on family caregivers in hematologic malignancies.— Harry VanDusen

Tweet this quote

Mr. VanDusen, also of Massachusetts General Hospital, reported similar results from the study he led in a group of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients and caregivers. “Patients undergoing [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] have significant symptom burden and a real deterioration in quality of life and mood during hospitalization. Through our previous work, we know family caregivers have significant distress during this acute period, as well,” he said, emphasizing the challenges within this group.

“Our study is the first to show a positive impact of a patient-focused palliative care intervention on family caregivers in hematologic malignancies,” Mr. VanDusen said.

The study enrolled 160 patients with hematologic malignancies within 72 hours of admission and 94 caregivers (mean age, 54 years). They were randomized to an integrated in-patient palliative care intervention (twice weekly or more visits) or to transplant care alone, with palliative care consult upon request. Family caregivers were welcomed but were not required at these visits. The study’s primary endpoint was impact of the intervention at week 2 of hospitalization, the time at which patients and caregivers demonstrate the greatest deterioration in quality of life, according to Mr. VanDusen.

As in Dr. El-Jawahri’s study, topics for the initial palliative care visit in Mr. VanDusen’s study were mostly symptoms (88.9%) and coping (85.2%); visits also aimed to build rapport (98.8%). The researchers used the HADS-D (depression subscale) and HADS-A (anxiety subscale) instruments and the 27-item Caregiver Oncology Quality-of-Life questionnaire tool to assess quality of life.

“We found less increase in depression symptoms at week 2 in the intervention group (P = .03), but anxiety scores and quality of life were not significantly different,” he reported. Analyses that adjusted for baseline scores, however, did show a significant intervention effect on depression, with a reduction of 1.65 on the HADS-D (P = .018), but anxiety and quality-of-life outcomes remained similar to those in the control group. Improvements in quality-of-life subdomains, coping (P = .009), and administrative/financial issues (P = .029) also emerged as significant. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Kent, Dr. El-Jawahri, and Mr. VanDusen reported no potential conflicts of interest.

References