Joseph Mikhael, MD, MEd, myeloma expert at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, Scottsdale, and Associate Dean of the Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education, considers five questions when selecting treatment for patients with multiple myeloma who relapse.

“With prolonged survival, which approaches 10 years in standard-risk patients, most patients will undergo many lines of therapy, and this will require a long-term approach that balances disease control with the elimination of clones,” Dr. Mikhael said in an interview with The ASCO Post.

“With many options available to the clinician, there is no simple or ideal sequence of treatments that has been established for treating relapsed disease. Balancing efficacy, toxicity, and cost will become ever more challenging with our increased options,” he noted.

It is possible to do this, he maintained, by asking five critical questions that form a practical algorithm. These questions will help clinicians differentiate this highly heterogeneous patient population. “We surely cannot treat all patients the same way,” he commented.

1. Does this patient really need to be treated now?

With slow, indolent relapse, certain patients—especially those with low-risk features—may be monitored closely (usually monthly), without intervention. “Identifying the ‘indolent’ vs the ‘aggressive’ relapse is crucial,” he emphasized.

With indolent relapse, it is reasonable to introduce a sequential approach using one or two agents at a time, usually a proteasome inhibitor or an immunomodulatory drug plus dexamethasone, eventually using all the active agents. This “control” approach is more likely to be useful in standard-risk patients. A more aggressive relapse requires a more aggressive treatment regimen, often using several agents in combination.

2. Should this patient be retreated with a previously used drug?

Retreatment with the same drugs that were used upfront is often necessary, and this may or may not be effective. Several factors can be predictive of efficacy in the relapsed setting: depth of the initial response (the deeper the response, the more likely that re-exposure will produce a response); duration of first response (at least 6 months predicts for a future response); and good tolerability of the agent. Bortezomib was approved for retreatment in 2014, he noted.

3. Have the ‘Big 5’ been used?

Five “novel” agents remain the center of myeloma therapy—thalidomide (Thalomid), lenalidomide (Revlimid), pomalidomide (Pomalyst), bortezomib (Velcade), and carfilzomib (Kyprolis). Although carfilzomib and pomalidomide are newer-generation agents, the others remain a critical part of treatment and have not been replaced, Dr. Mikhael indicated.

For the immunomodulatory drug class, thalidomide is best used late in the disease course, in patients who cannot tolerate myelosuppression, and in combination (especially with bortezomib/dexamethasone or with cyclophosphamide/bortezomib/dexamethasone). Lenalidomide has shown a survival advantage in large phase III trials and is successfully combined with bortezomib and carfilzomib. Pomalidomide is highly active in combination with dexamethasone and has been effectively combined with bortezomib and carfilzomib.

For the proteasome inhibitors, bortezomib can be effectively used alone or in combination with immunomodulatory drugs (including pomalidomide) and cyclophosphamide. Carfilzomib can be widely used, even in bortezomib-refractory patients, alone and in combination with essentially all other myeloma agents.

Dr. Mikhael commented on the role of the two newest agents, carfilzomib and pomalidomide. “With very similar indications for relapsed myeloma, deciding between these two agents is a common clinical problem,” he noted. “It should be reassuring to clinicians that each myeloma patient is likely ultimately to see both agents, and the optimal sequence is not yet known.”

Several factors can help clinicians choose between these agents (both of which are effective in high-risk disease). Factors favoring carfilzomib include the presence of renal insufficiency and preexisting neuropathy, whereas pomalidomide is favored when convenience of administration is important and in patients with poorly controlled heart failure or hypertension.

“Class ‘switching’ is not necessarily supported by evidence,” he pointed out. This means that bortezomib-refractory patients may respond to carfilzomib, and lenalidomide-refractory patients may respond to pomalidomide.

Evidence is emerging that these two drugs are effective when combined, and therefore this doublet should be considered in aggressive relapse. The addition of the second agent when patients do not respond or progress on the other can also be considered.

Elaborating on combinations of agents, Dr. Mikhael added that even when patients become resistant to a certain agent, they may become sensitive to it again, due to clonal evolution or because of something that occurs when the drug is combined with another. He noted that about 30% of patients who are resistant to bortezomib and dexamethasone respond to the combination of bortezomib/lenalidmide/dexamethasone (VRD).

4. Have the ‘add-on’ agents been used?

Although the five key agents discussed here are considered the backbone of myeloma treatment, several others have activity that can enhance their efficacy: corticosteroids (dexamethasone weekly [20–40 mg], alternate-day prednisone (25–100 mg), alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide, melphalan), and liposomal doxorubicin. These agents can also be considered without a novel agent on board (ie, cyclophosphamide/prednisone).

5. Has an individualized, risk-stratified approach been considered?

“A patient’s risk status may indeed influence the selection of relapsed therapy. Standard-risk patients may only require single-agent approaches. Intermediate-risk patients will likely benefit from bortezomib-containing regimens. And high-risk patients require more intense combination regimens to effectively control their disease,” he indicated.

Elaborating on individual risk, Dr. Mikhael noted that relapse occurs sooner and more aggressively in high-risk patients and that close monitoring and rapid initiation of treatment in these patients are critical. Risk factors may change since the time of first diagnosis, so patients should be reevaluated upon relapse.

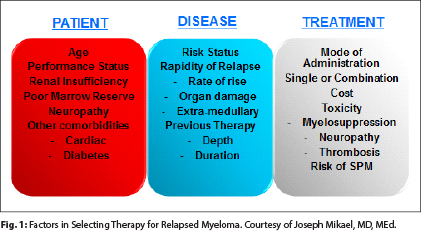

In addition to risk tier, several other patient factors should be considered because they may also influence the choice of treatment, especially age, performance status, renal insufficiency, bone marrow reserve (previous myelosuppression), preexisting neuropathy, and other comorbidities, such as cardiac disease and diabetes (see Fig. 1 on page 59).

Other Approaches

Autologous stem cell transplantation remains the standard of care for frontline therapy in eligible patients, although some may defer transplantation until relapse. However, a second autologous stem cell transplantation is also feasible as salvage later in the disease course assuming three criteria are met: (1) the patient responded to the first autologous stem cell transplantation, (2) the patient tolerated the first autologous stem cell transplantation, and (3) the patient did not progress for at least 2 years after autologous stem cell transplantation. When these conditions are met, patients can expect a progression-free survival that is 50% to 70% that achieved with the first autologous stem cell transplantation, he said.

Alternative approaches include allogeneic bone marrow transplant and high-dose chemotherapy. Allogeneic transplant remains controversial, based on the availability of novel agents and high treatment-related morbidity and mortality.

“My approach is that only patients meeting four requirements will be candidates for allogeneic transplant,” he said. They must be “young,” have genotypically high-risk disease, and have phenotypically high-risk disease (ie, relapsing quickly), and the transplant should not be used as a “Hail Mary” after all other strategies have failed.

High-dose chemotherapy (such as DT-PACE [dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide]) may produce responses in about 50% of patients, although they tend to be short-lived. “This approach is likely best used as a bridge to a more definitive therapy or clinical trial,” he maintained.

Dr. Mikhael hailed the emergence of new agents, especially those with new mechanisms of action. Monoclonal antibodies, histone deacetylase inhibitors, immune therapies, and agents directed toward new targets will expand the landscape of treatment and will likely further improve survival in myeloma, he predicted. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Mikhael has received institutional research funding from Onyx, Celgene, Sanofi, and AbbVie.