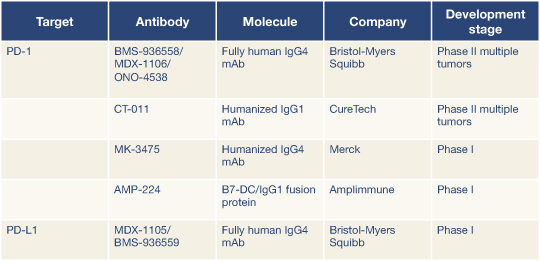

Oncologists can expect to hear more about immune checkpoint blockade, according to two discussants of these abstracts. In fact, five PD-1 immune checkpoint compounds are already in the pipeline (Table 1), according to Giuseppe Giaccone, MD, PhD, of the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

James Allison, PhD, of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Immunotherapy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said immunotherapy has turned a corner to become a “compelling” means of treating cancer, thanks to better understanding of the complexity of T-cell regulation.

“Antibodies to regulatory molecules take the brakes off the immune system, free T cells to proliferate, and maximize [antitumor] response,” he said. “And you are treating T cells, not tumor cells, so the tumor type should be irrelevant. Furthermore, the immune system can adapt; you don’t get resistance. And T cells can provide memory.”

The effect of unleashing a memory immune response may be long-term disease stabilization, he predicted. “Once T cells are stimulated by engagement of peptides, you get long-lived memory that may last for the life of the patient…. In fact, I recently saw a patient who was on the phase I melanoma trial of ipilimumab 10 years ago. She is alive, without need for subsequent treatment…. With ipilimumab, survival at 2 years is about 25%, and it stays at this rate for 4 or 5 years, due to immunologic memory, though we see this in just a fraction of patients.”

Responses lasting up to 2 years are being seen with PD-1 immune checkpoint drugs, but the question is, he said, “Can they be as long as those with ipilimumab?”

Patient Selection Will Be Key

Commenting on the findings for the anti–PD-1 antibody, Dr. Giaccone noted, “BMS-936558 has promising activity in NSCLC, and appears to be better tolerated than the CTLA4 antibody, though severe pneumonitis was seen, resulting in three deaths. It is potentially more effective in squamous carcinoma histology, where we do not have effective targeted agents. Patient selection—ie, biomarkers—should be sought. Combination studies are warranted. And randomized studies will be needed to confirm these benefits.”

Dr. Allison added that if efficacy is restricted to tumors expressing PD-L1, patient selection can be optimized. He agreed that combination therapy may increase the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade and might be achieved with vaccines, other checkpoint inhibitors, conventional therapies and targeted therapies, and through stimulation of costimulatory pathways.

“As we learn to combine these drugs, we will see progress,” he predicted. “But we are already lucky. In a 2-year period, we have learned about two distinct pathways and have developed agents with clinical activity in a large number of patients.”

In an editorial accompanying the New England Journal of Medicine publications, Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, suggested that PD-1 inhibitors may have fewer side effects and “even greater activity” than CTLA4 inhibitors.1 He said the newer agents have “broken the ceiling” of durable tumor response rates, are likely “to provide a new benchmark for antitumor activity in immunotherapy,” and “may well have a major effect on cancer treatment.” ■

Disclosure: Dr. Giaccone reported no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Allison reported that he is the inventor of intellectual property held by the University of California, Berkeley, licensed to Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer, and he receives royalties from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Ribas has served on ad hoc advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck.

Reference

1. Ribas A: Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. June 2, 2012 (early release online).