A Century of Progress

The text and photograph on this page are excerpted from a four-volume series of books titled Oncology Tumors & Treatment: A Photographic History, by Stanley B. Burns, MD, FACS. The photo below is from the volume titled “The Radium Era 1916–1945” by Stanley B. Burns, MD, FACS, and Elizabeth A. Burns. The photograph appears courtesy of Stanley B. Burns, MD, and The Burns Archive. To view additional photos from this series of books, visit burnsarchive.com.

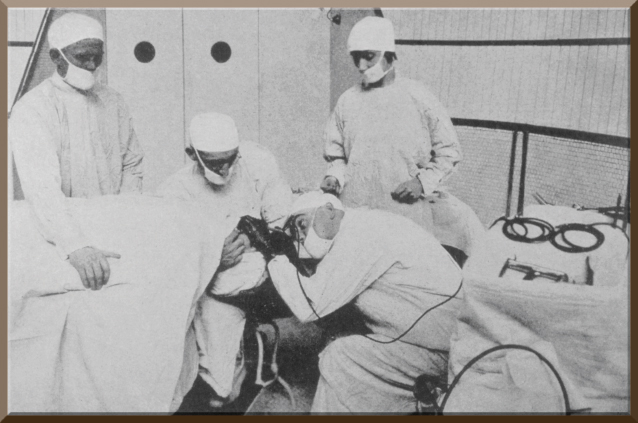

Endoscopic examination of the intestinal tract remains a prime diagnostic tool for positive identification of cancers. Endoscopic instruments also aid in the retrieval of tissue for biopsy, providing a more accurate diagnosis and help in the staging of tumors. This is a photograph of the pioneer bronchoesophageal endoscopist Chevalier Jackson, MD (1865–1958), performing an esophageal endoscopy.

Generally, the invasion of the intestinal tract was performed only in case of a medical emergency. For centuries, physicians would force down the esophagus a simple tube, a bougie, a sound, or anything that was thought to be useful, in a desperate attempt to dislodge an object. Unusual examples of various means used to remove or displace obstructions are scattered throughout the medical literature. The occasional success encouraged physicians to continue their efforts.

In 1882, Bernard Randolph Conrad von Langenbeck, MD (1810–1887), reported the case of a woman who swallowed the eroded bony remnant of her nose while asleep. She suffered from nasal destruction, a common accompaniment of tertiary syphilis. The bone was eventually removed by surgery.

Dr. Jackson reported a case of a 6-year-old boy who choked on what was thought to be a bone; he was hospitalized and anesthetized, and two surgeons spent hours using elongated forceps in a blind attempt to remove the object. The object they kept grasping could not be dislodged. The patient died. Two days later at the autopsy, it was found the surgeons had pushed through the esophagus and were trying to remove a vertebra. All tissue had been stripped from the vertebra. Ultimately, Dr. Jackson’s promotion of esophagoscopy saved the lives of those with obstructions of the esophagus, but its true role was in diagnosing ulcers, erosions, and cancers.

Early Esophagoscopes

Primitive esophagoscopes were first developed about 1868 by both Bevan of Guy’s Hospital in London and Louis Waldenburg, MD (1837–1881), in Berlin. Also, in 1868, a medical landmark procedure was developed by Adolf Kussmaul, MD (1822–1902), of Freiberg. He performed what is considered the first esophagoscopy using an elongated scope developed for urethral and bladder examination by Doctor Antonin Jean Désormeaux (1815–1894) of Paris. Dr. Désormeaux and his pupil had formally attempted esophagoscopy with their primitive instrument, with little success.

Dr. Kussmaul also used this instrument to diagnose a carcinoma at the level of bifurcation of the trachea. He worked with a sword swallower and began to design his own endoscope. He fashioned a 47 mm x 13 mm tube easily tolerated by the sword swallower; however, the light source was not adequate and had to be improved. He traveled to various clinics, with the sword swallower demonstrating the procedure. He helped make esophagoscopy a viable procedure.

The invention of the modern cystoscope by Max Nitze, MD (1848–1906), in 1877 and the light bulb by Thomas Edison in 1879 led to the development of a flexible illuminated esophagoscope. Johann von Mikulicz, MD, of Vienna, developed one of the first of these instruments and performed numerous procedures.

‘High-Low’ Method

In the 1880s, the “hanging head” position was introduced, in which the patient lies supine on his back with his head tilted over the edge of the operating table. Dr. Jackson used this position as one of the foundations of his technique and labeled it the “high-low” method. Although some European operators, such as Dr. Mikulicz, initially used chloroform as anesthesia, Dr. Jackson used topical cocaine. Carl Stoerk, MD, and Victor Ritter von Hackler, MD, introduced this form of anesthesia in 1877. Several other physicians, including Wilheim Bruning, MD, and Max Einhorn, MD (Lenox Hill Hospital), continued to improve the instrument.

Dr. Jackson’s expertise and fame led to the establishment of instructional courses in bronchoesophagoscopy in both Philadelphia and Paris. A major drawback in his teaching technique was his use of anesthetized dogs as subjects rather than humans. To their advantage, European teachers used humans. Dr. Jackson continued to use dogs, even though it was acceptable to practice on human subjects in Paris.

European clinics hired both “professional patients,” those who were able to pass a scope without retching and without anesthesia, as well as those addicted to cocaine. In Vienna, there was a woman who inhaled tacks into her bronchi for postgraduate students to remove.

When x-rays were discovered, radiology became an additional tool to assist in the identification of foreign objects. In 1901, Guido Holzknecht, MD, of Vienna established the principles of esophageal radiography, and radiologically guided esophagoscopy became the standard. This photograph shows Dr. Jackson performing his “high-low position” sequence for esophagoscopy. The esophagoscope was inserted while in a “high” position. Jackson notes:

Stage 1: Finding the right pyriform sinus. In this and the second stage, the patient’s vertex is about 15 cm, above the level of the table and in full extension.... Stage 2: The scope is passed beyond the cricopharyngeal fold; it is noted that the cervical esophagus presents almost no resistance to the tube.... Stage 3: The esophagoscope usually glides easily through the thoracic esophagus.... The levels of the aorta and left bronchus are readily recognized, and in passing them, the lumen of the esophagus seems...to disappear anteriorly. This is the signal for lowering the head.... Stage 4: (Once lowered) This brings the tube mouth quickly to the hiatal constriction (with firm gentle pressure, it is passed).... The abdominal esophagus is 2 to 4 cm. (The stomach is then entered.)

By the end of the 20th century, computers, fiber optics, and miniaturized instrumentation evolved and morphed endoscopy. ■