A well-documented flaw in paper-based health care is the propensity for medical errors. According to Blackford Middleton, MD, MPH, MSc, implementing clinical decision support software can decrease medical error, improve outcomes, and lower the costs of care. Presenting a session titled “Improving Quality Through HIT” at the recent ASCO HIT/EHR [Health Information Technology/Electronic Health Records] Symposium in Atlanta, Dr. Middleton led off with a slide of an actual hand-written prescription. He asked an audience member to identify the drug and dose. When the doctor called out the answer, Dr. Middleton said, “Wrong—that’s the first medical error of the day.”

A well-documented flaw in paper-based health care is the propensity for medical errors. According to Blackford Middleton, MD, MPH, MSc, implementing clinical decision support software can decrease medical error, improve outcomes, and lower the costs of care. Presenting a session titled “Improving Quality Through HIT” at the recent ASCO HIT/EHR [Health Information Technology/Electronic Health Records] Symposium in Atlanta, Dr. Middleton led off with a slide of an actual hand-written prescription. He asked an audience member to identify the drug and dose. When the doctor called out the answer, Dr. Middleton said, “Wrong—that’s the first medical error of the day.”

Dr. Middleton is Corporate Director of Clinical Informatics Research & Development at Partners Healthcare System, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard School of Public Health.

The High Cost of Paper

The seminal 1999 Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human,1 exposed the prevalence and effect medical errors have on our health-care system. More than a decade later, the problem still exists. HIT might offer solutions, Dr. Middleton maintained.

The seminal 1999 Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human,1 exposed the prevalence and effect medical errors have on our health-care system. More than a decade later, the problem still exists. HIT might offer solutions, Dr. Middleton maintained.

“Paper-based medicine has served a purpose over the millennia. However, it is prone to error, and while it collects a lot of information, it offers no platform for data analyses or communication. And since it doesn’t integrate with e–health care, paper will not be part of the transformation of our health-care system,” Dr. Middleton noted.

Citing research from several large health-care institutions and publications in the literature, Dr. Middleton highlighted the extent of medical errors. For instance, he offered these statistics from the outpatient setting: For every 1,000 patients receiving care, about 14 life-threatening or serious adverse drug events are reported; out of 1,000 written prescriptions, about 40 contain medical errors; and out of 1,000 women with a marginally abnormal mammogram, approximately 360 women will not receive follow-up care.

“On the inpatient side, there is an estimated error rate of about 10.7 per 1,000 patient-days. Moreover, we see estimates of serious medication error at 5.3% of admissions in New York teaching hospitals,” Dr. Middleton said, stressing that medication errors occur in approximately 1 of every 20 admissions.

“Medication error is seen in a wide variety of medical activities. However, nearly 50% of errors happen in the ordering process, after the diagnostic and therapeutic decisions are made. About 26% of errors take place in the administration/management cycle. So we need to think of ways to address the vulnerable areas in the process, because the costs are substantial,” Dr. Middleton said. Studies show that it costs about $2,462 per adverse drug event and about $4,555 per preventable adverse drug event, he observed.

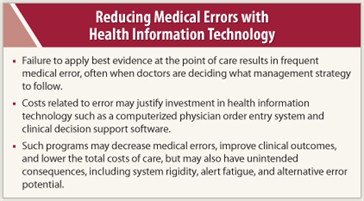

“These figures exclude the costs of injuries to patients, malpractice suits, and admissions due to adverse drug events. The data indicate that a large percentage of medication errors occur at the point of care, when doctors are deciding what management strategy to follow,” Dr. Middleton said. Moreover, the costs related to error justify investment in a computerized physician order entry (CPOE)/clinical decision support software package, he maintained.

HIT Reduces Costs

One advantage of a clinical decision support system is that it is integrated into the clinical workflow rather than as a separate login or screen, allowing the system to interact at the point of care, where many of the prescribing errors occur. “The literature is rife with studies making the case for adoption of clinical decision support software, citing evidence that this software increases adherence to guideline-based care and offers enhanced surveillance and monitoring, which leads to decreased medication errors,” Dr. Middleton observed.

One advantage of a clinical decision support system is that it is integrated into the clinical workflow rather than as a separate login or screen, allowing the system to interact at the point of care, where many of the prescribing errors occur. “The literature is rife with studies making the case for adoption of clinical decision support software, citing evidence that this software increases adherence to guideline-based care and offers enhanced surveillance and monitoring, which leads to decreased medication errors,” Dr. Middleton observed.

Myriad examples in the literature demonstrate that employing the various iterations of HIT can save the health-care system money, he pointed out. For instance, the effects of electronic health records, computerized physician order entry, health information exchanges, telehealth, and personal health records reduce medical errors, hospitalizations, redundancy of tests and procedures, and administrative costs.

“In one study we did at Partners Healthcare and Harvard Medical School, we summarized the evidence base for the value of an ambulatory CPOE system. After a thorough literature evaluation, we built a large simulation model with about a thousand different variables and estimated the impact of a CPOE system on the ambulatory outpatient visits,” Dr. Middleton said.

Based on their model, Dr. Middleton and his colleagues found that for an “average” provider, an advanced CPOE system would prevent:

- 9 adverse drug events per year

- 6 adverse drug event–related office visits

- 4 adverse drug event–related hospital admissions

- 3 life-threatening adverse drug events

“We calculated that the savings from the CPOE system in this study was worth about $44 billion in the aggregate when you roll it up against 1.1 billion outpatient health-care visits per year,” he commented. According to Dr. Middleton, most of these models are most sensitive to prospective payment or the degree of capitation in a particular delivery environment. “This makes good sense,” he continued, “Because often he who pays for health-care IT is not he who gains. In our models for ambulatory CPOE, the benefit is actually distributed 89% to the payer, and the rest of the benefit goes to the provider, which is directly related to the percentage of capitation or at-risk contracts you have.”

Testing the Hypothesis

Dr. Middleton’s work showed that computerized physician order entry was effective, largely because the physician is at the order entry point. He postulated that decision support for physicians might be even more effective if applied throughout the cycle of the physician-patient encounter or a hospitalization.

To test the hypothesis, Dr. Middleton and his associates built a system called the CAD/DM SmartForm for coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus. (A SmartForm is a problem-oriented, documentation-based clinical decision support system that actively engages clinicians during patient visits.)

“Instead of providing decision support at the point of order entry, this system provides support throughout the chart review, previsit, and the visit itself, thoroughly documenting the encounter. In this system, we key up the appropriate data and documentation of the encounter to review, but most importantly, we provide an assessment of what the patient needs,” he explained.

Dr. Middleton and associates concluded that SmartForms address quality deficiencies by delivering actionable decision support to the point of care, with rigorous attention to clinician workflow. These novel tools work together to increase the self-evident value of EHRs to clinicians and improve the quality of medical care.

He noted that one downside is the cost of the more sophisticated system. “We had a couple of hundred different rules working at all times. So the knowledge engineering costs of this level of advanced decision support is actually pretty high and might currently be beyond the capacity of most institutions across the country.”

Conclusions

In summary, Dr. Middleton balanced the pros and cons of current health information technology relating to clinical decision support. Clinical decision support systems can decrease medical errors, particularly around medications. The systems can improve clinical processes and outcomes and lower the total costs of care.

“However, we also need to be concerned about possible unintended consequences of clinical decision support systems, such as rigidity of the system, alert fatigue, and potential for errors. Further research should focus on improving the relevance of clinical decision support software and knowledge sharing,” Dr. Middleton concluded. ■

Disclosure: Dr. Middleton reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Reference

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS (eds): To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC; National Academies Press; 2000. Available at http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=0309068371. Accessed November 17, 2011.