Could the manipulation of bacteria in the gut pack the same punch in melanoma as antibodies targeting the programmed cell death protein and its ligand (PD-1/PD-L1)? It’s possible, at least in mice, according to research from the University of Chicago, recently published in Science.1 The researchers reported that oral administration of Bifidobacterium alone improved tumor control to the same degree as anti–PD-L1 therapy and that the combination treatment nearly abolished tumor growth.

“Our data suggest that manipulating the microbiota may modulate cancer immunotherapy,” wrote Ayelet Sivan, MD, and colleagues. Senior author Thomas Gajewski, MD, PhD, a melanoma expert who is Professor of Medicine and Pathology at the University of Chicago, added: “Our results clearly demonstrate a significant, although unexpected, role for specific gut bacteria in enhancing the immune system’s response to melanoma and possibly many other tumor types.”

Co-Housing and Shared Bacteria

The checkpoint inhibitors ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) have produced robust responses in advanced melanoma—although not in the majority of patients. The reasons for this lack of response remain unclear.

Dr. Gajewski and his group found a similar pattern in mice implanted with melanoma tumors. From two different facilities, they obtained mice that were genetically similar but different in terms of their commensal gut microbes. It turned out the two groups also differed in their immune response to the presence of melanoma.

Tumors grew slowly in the Jackson Laboratory mice, whereas they grew aggressively in mice from Taconic Biosciences. This difference appeared to be immune-mediated, since tumor-specific T-cell responses and intratumoral CD8-positive T-cell accumulation were significantly higher in the Jackson vs Taconic mice, the researchers reported.

However, when the mice were mixed and housed together, these differences in tumor growth were abolished. The researchers hypothesized that by sharing exposure to various types of bacteria, the Taconic mice acquired microbes from the Jackson mice, which somehow enhanced their immunity to the tumors.

Their hypothesis was validated when they transferred fecal matter from the Jackson mice to their weaker Taconic peers; thereafter, these mice were able to mount a strong immune response against the tumors. The transfer was sufficient to delay tumor growth and enhance induction and infiltration of tumor-specific CD8-positive T cells, supporting a microbe-derived effect, they wrote. Reciprocal transfer of fecal matter of Taconic mice into Jackson mice recipients had little effect on tumor growth and antitumor T-cell response.

Comparing Bacteria With Anti–PD-L1 Agent

The researchers then compared the immune response after bacterial transfer of Jackson mice fecal matter with the effect of anti–PD-L1 antibodies (they used a mouse compound that is similar to the available agents for humans). Transfer alone resulted in significantly slower tumor growth, accompanied by increased tumor-specific T-cell responses and infiltration of antigen-specific T cells into the tumor to the same degree as seen with anti–PD-L1 agents, they reported. When the two approaches were combined, the researchers observed enhanced tumor control and circulating tumor antigen–specific T-cell responses.

The group then performed large-scale sequencing of microbes in the digestive tract, to determine the type of bacteria responsible for the immune response. Although they found significant differences in 254 taxonomic families of bacteria between the two mouse populations, Bifidobacterium stood out as the most abundant in the Jackson cohort.

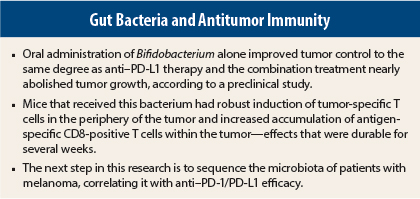

To further test the power of Bifidobacterium, they administered this strain to the Taconic mice alone and in combination with anti–PD-L1 agents. Mice that received this bacterium displayed significantly improved tumor control vs their counterparts who did not; they had robust induction of tumor-specific T cells in the periphery of the tumor and increased accumulation of antigen-specific CD8-positive T cells within the tumor—effects that were durable for several weeks.

Oral administration of Lactobacillus murinus, on the other hand, had no effect on tumor growth or T cell response, suggesting that modulation of antitumor immunity depends on the specific bacterium administered.

“Collectively, these data point to Bifidobacterium as a positive regulator of antitumor immunity in vivo,” they concluded.

Additional tests showed that the bacteria probably triggered the immune response by interacting with roaming dendritic cells. This augmented dendritic cell function led to enhanced CD8-positive T-cell priming and accumulation in the tumor microenvironment. Further investigations revealed evidence of enriched pathways for genes shown to be critical for antitumor responses.

Applicable to Humans?

With animal experiments, the pivotal question is always whether the findings will be applicable to humans someday. To this question, Dr. Gajewski answered, “Yes. We are excited about the possibility that similar associations between specific gut bacteria and clinical outcomes with checkpoint blockade therapy might be found in humans. If so, then it should be possible to develop a probiotic to improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies.”

The group’s next step is to sequence the microbiota of patients with melanoma, correlating it with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 efficacy. “We think examining the clinical relevance of this effect should receive high priority,” Dr. Gajewski told The ASCO Post. “In addition, we are extending our laboratory work to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved and also to investigate whether additional types of bacteria beyond Bifidobacterium impact antitumor immunity—either positively or negatively.” ■

Disclosure: For full disclosures of the study authors, visit www.sciencemag.org.

Reference

1. Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, et al: Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. November 5, 2015 (early release online).