Osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with cancer treatment is frequently misunderstood, according to Cesar Augusto Migliorati, DDS, MS, PhD, who delivered an update on its proper recognition and management at the 2015 Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) International Symposium on Supportive Care in Cancer in Copenhagen.1 Dr. Migliorati dispelled some common myths about osteonecrosis of the jaw and presented information that may be new to many clinicians.

Bisphosphonates and Beyond

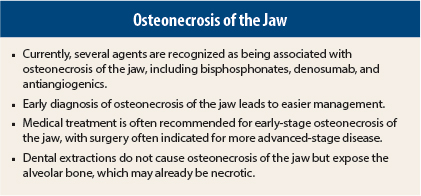

Currently, several agents are recognized as being associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw, including bisphosphonates, denosumab (Prolia, Xgeva), and antiangiogenics. “A lot of people still call it bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw, but it’s no longer a bisphosphonate problem only,” said Dr. Migliorati, Professor and Chair, Department of Diagnostic Sciences and Oral Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis.

“Further, we know now that if you combine bisphosphonates with antiangiogenics in advanced renal tumors, there is an increased risk for this condition to occur. So that’s another new recognized risk factor for this condition,” he added.

Recognizing Symptoms

According to a 2014 update from the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS),2 patients may be considered to have osteonecrosis of the jaw if the following characteristics are present: current or previous treatment with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic agents; exposed bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than 8 weeks; and no history of radiation therapy to the jaw or obvious metastatic disease to the jaw.

Dr. Migliorati recommended first thoroughly evaluating a patient’s history, including history of medications; oral complaints (pain, discomfort, tingling/paresthesia, bad breath, pus, swelling); dental history; and past treatment of an oral problem, including any history of surgery, trauma, and/or use of local and systemic antibiotics.

Next, the patient should be examined for exposed bone and/or infection, purulent secretion, abscess formation, and fistula. Finally, a radiographic evaluation should be conducted.

Risk Factors

The presence of certain factors may place patients at higher risk for osteonecrosis of the jaw, warned Dr. Migliorati. They include the use of medications for osteoporosis or cancer that have been associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw, the presence of active dental/periodontal disease, and individual predisposition. The latter “should be considered since the majority of patients on these medications do not develop osteonecrosis,” he said.

Situations that may affect a person’s risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw include the duration on any drug associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw (the longer the duration, the higher the risk), a switch from a bisphosphonate to denosumab, and concomitant use of a bisphosphonate plus an antiangiogenic agent.

“In our experience adjudicating thousands of cases, we think there may be an additional risk, and patients can develop osteonecrosis of the jaw in a short period (sometimes 1 month) after the first injection of denosumab,” he stated. “So this is something we still have to learn more about.”

Dental Extractions

In patients taking antiresorptives, dental extractions have been blamed as the cause for osteonecrosis of the jaw. “We have always questioned this possibility because there was never an explanation of the diagnosis that led to the extraction,” Dr. Migliorati explained.

“Every time a dental extraction is performed, there is a diagnosis for it—most commonly an infection that has destroyed the bone support of the tooth or a fracture of the tooth that can’t be restored,” he said. “So we need to know why the teeth are being extracted, rather than blaming the extraction.”

Patients heal from dental extractions when the wound is well handled, antibiotics are used, and patients are monitored, he reported. “So we can treat patients rather than sending them home with an active infection and saying ‘I can’t treat you because of the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw.’ So that concept is changing completely.”

Dr. Migliorati and his colleagues are currently collaborating with a group in Greece on this topic. “We want to publish proof that dental extractions do not cause osteonecrosis of the jaw but expose the alveolar bone, which may already be necrotic,” he said.

Surgical or Medical Treatment

Once osteonecrosis of the jaw has been recognized, a decision must be made regarding treatment—medical or surgical. This decision can be influenced by the general health and cancer prognosis of the patient, a patient quality-of-life evaluation, and the patient’s initial response to cancer therapy.

“The earlier the diagnosis, the easier the management,” said Dr. Migliorati. When osteonecrosis of the jaw is classified as AAOMS stages 0 to II, he recommended frequent follow-ups, encouraging the use of antimicrobial rinses, prescribing systemic antibiotics when there is active infection or signs of paresthesia, and performing minor local debridement to eliminate sharp bone edges that could aggravate the oral mucosa.

For patients in a more advanced stage of osteonecrosis of the jaw (AAOMS stage III) who have not responded to treatment, Dr. Migliorati recommended surgical intervention with resection, bone and soft-tissue grafting, and primary closure of the defect. Reconstruction of the surgically resected bone with titanium bars may be necessary in more advanced cases, when the defect is too large, he stated.

“The use of antiresorptives is not going to go away, but rather continue to increase, so the chances are good that we’re going to be seeing more of these cases,” said Dr. Migliorati. “We have to learn to recognize them quickly, make a correct diagnosis, and then manage them as soon as possible.” n

Disclosure: Dr. Migliorati is a consulant for Amgen and Colgate Palmolive.

References

1. Migliorati C: Recognition and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw. 2015 MASCC/ISOO International Symposium. Parallel Session PS11. Presented June 26, 2015.

2. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al: American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72:1938-1956, 2014.